CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines Ben Stokes’ curiously mediocre T20 record, and considers whether, despite the undoubted moments of brilliance, he might not be in England’s best T20I side.

Last year, in 2019, there were two innings which will go down in Test history: Kusal Perera’s 153* against South Africa, and Ben Stokes’ 135* against Australia.

Two fourth innings chases, with the winning side coming through nine down, the odds stacked against them right up to the moment of victory. Both took away the breath of the global cricket community, both sent shockwaves around the world. Immediately after Stokes’ knock, people clambered over each other to compare the innings’, to determine which was better by clear empirical metrics.

It was a shame, because given the two players involved, these innings were remarkable for two entirely different reasons.

For Kusal Perera, a talented but inconsistent batsman without much of a profile outside of cricket, it was magical because nobody believed he was capable of playing such an innings.

For Ben Stokes, it was magical because everyone believed.

***

Ben Stokes is having a horrible few months. The tension and uncertainty of the coronavirus pandemic is causing us all distress, some far more than others. England’s all-rounder has been coping with all that just like the rest of us, but with the added strain and stress of visiting his father, Ged, in New Zealand, who is fighting cancer. The personal hardship is obvious and harrowing, and came with large professional consequences. Stokes’ visit cut short his cricketing summer, and delayed the start of his IPL campaign for Rajasthan Royals. He’s shown an admirable commitment to putting family first, and placing cricket – the least important of the important things – in context, in perspective, and firmly to one side.

So, this is a piece written with its eyes purely on the cricket field and, for better or worse, ignoring what has gone on beyond it. If one had been working with that tunnel vision for the last few years, looking at the field, one question would be at the forefront of your mind.

Is Ben Stokes actually in England’s best T20 side?

On Thursday evening, Stokes made 30 (32) as Rajasthan Royals stumbled to a losing first innings total of 154-6, before he delivered a wicketless two over spell which cost 24 runs. It was a chastening evening that leaves Rajasthan on the brink of elimination, needing results to fall in their favour over the next week, but this wasn’t judging Stokes the T20 player by one night – it was an evening which summed up Stokes’ season. From four matches, a batting average of 22 and a scoring rate of 6.4rpo; no wickets from 48 balls, with an economy of 10.3rpo.

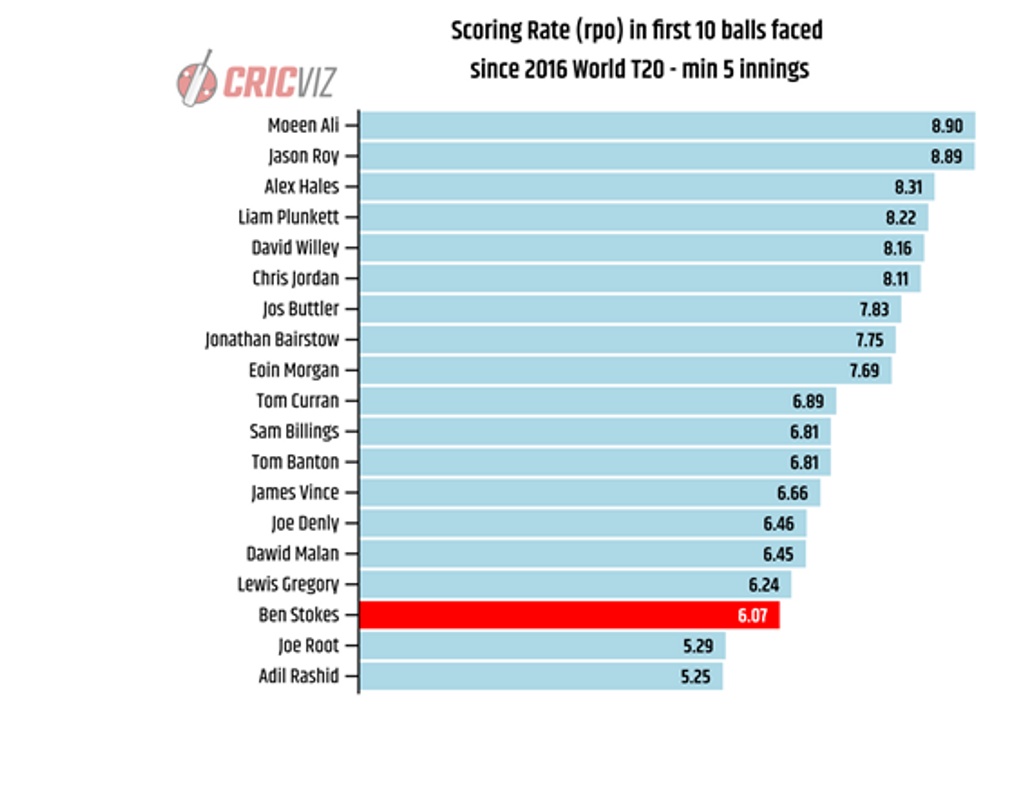

Equally, looking at that record and feeling a touch queasy isn’t judging him by one season. Those sort of underwhelming numbers are nothing new for Stokes: for England since the 2016 World T20, Stokes averages 23 with that bat and scores at 7.4rpo, averaging 33 with the ball at an economy of 8.2rpo. In domestic cricket, all over the world, it’s not much different. His record in T20 cricket is not good.

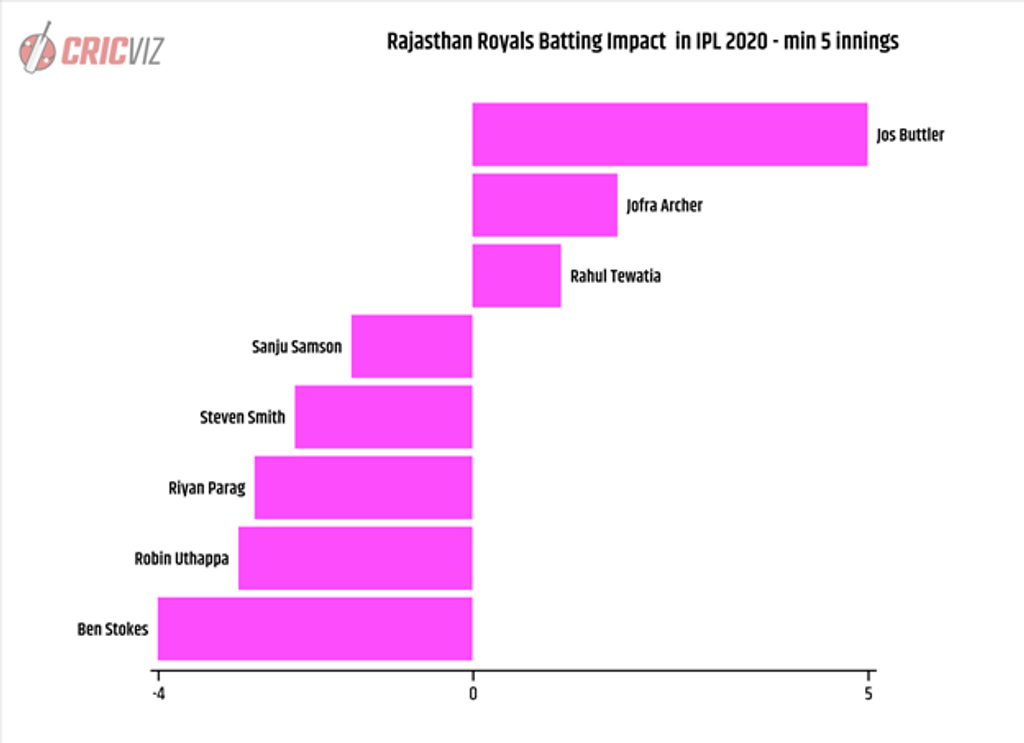

With bat, Stokes is not the explosive player we know from elsewhere. A feature of Stokes’ batting across all formats is slow acceleration then top gear attack, but naturally in T20 that slow acceleration has more obvious downsides. A Batting Impact of +1.1 is good, showing he’s better than the average batsman – but not by much.

With ball, he’s never quite nailed a role. It’s a quirk of his game that Stokes, so adept at swinging the red ball, has never found it as easy to swing the white ball. If he could – picture a quicker, right-handed David Willey – then Stokes would be a very different prospect. As it is, in a format which reduces the impact of his legendary fitness and stamina, Stokes’ pace is his main weapon, and while a Bowling Impact of +0.9 again shows he’s better than the average bowler, it’s marginal. Relying on Stokes to bowl overs in T20Is is a gamble – his value in T20 needs to come from his batting.

There is a depth to English limited-overs batting that is envied by almost every side the world over, and perhaps coincidentally, the debate over selection has started to intensify in England. People are paying attention, because World Cups focus the collective mind. Debate over the inclusion or exclusion of Dawid Malan from the T20I side when England are at full strength has been conducted with the same tone of passion and care as debates around Test selection. Realistically, England are trying to squeeze Malan, Jason Roy, Jonny Bairstow, Eoin Morgan, Jos Buttler, Moeen Ali, Tom Banton and Ben Stokes himself, into the top six. Morgan aside, all of them would prefer to open the batting and for now, Stokes is at the bottom of that queue.

There are broader, tactical questions to ask and answer here. How does Stokes actually fit into England’s natural pattern of selecting a side? Eoin Morgan’s men have played with a few different formations of late, with some suiting Stokes more than others. Of late, England have moved from a formation of four frontline bowlers plus Stokes and Moeen (in essence playing the extra batsman and fudging the fifth bowler), to including a bowling all-rounder at No.7, a role that in the last two T20I series’ has been filled by Tom Curran and Chris Jordan, but which could also be one suited to Sam Curran. With a longer tail, Stokes’ ODI pedigree becomes more valuable, because preserving wickets is more important.

There are intangibles here. Stokes has rarely had an opportunity to give T20 cricket his full focus, given his rare all-format capabilities. That naturally puts a cap on his T20 performance, and leaves open the possibility that with a global tournament acting as an incentive and focus, he could improve. In terms of attack balance, Stokes’ extra pace is useful, depending on the balance of the side; if Wood and Archer go top and tail, leaving the spinners and Currans to prowl through the middle, then Stokes’ ability to act as an enforcer against batsmen who struggle against the short ball is valuable. On top of all that, his fielding – albeit a much-overrated discipline – is excellent, giving England a boost were Jordan to slide out of the side.

The thing is, we can dance about all we like with numbers and thoughts, but this is Ben Stokes. The hero not just of Headingley, but the World Cup, the 2017 IPL MVP, a man who has reached his own pinnacles in every format.

As a result, hovering there in the back of our minds is this idea that Stokes is special. This is not a foolish thought. In the run up to the ODI World Cup, he was performing at a mediocre level (the year before he was scoring at 4.5rpo and he took only five wickets across 2019), before exploding into the form of his life with the bat, at the exact moment it mattered. In Tests, he was so-so for a number of years (albeit while he was establishing himself) before, in the aftermath of Bristol and all that it brought, he returned a grooved and effective player with bat and with ball. The player we saw at Lord’s last year, and Headingley a month or so later, had his chance because people believed in him.

Faith in this talent cuts both ways. You get moments like the World Cup final, and the last day in Leeds, but you also get a player who, with an objective eye, has a middling record in these formats. Stokes’ improvement has been remarkable but we are still looking at a man averaging 38 and 32 in Test cricket with bat and ball. His purple patch of form since the start of 2019 sees him average 50.41, and while the moments trump the mean every day of the week, even at his best Stokes is inconsistent. If Stokes’ record was simply brilliant, then we wouldn’t get as excited about him. We’d all just acknowledge that here is a great player playing well, just like we do with Joe Root. But that isn’t the dynamic – what we have, is a player who perhaps more than anyone else in the world, is capable of transcending their record, and reaching new levels. He invites trust but he also requires it.

The trade-off with Stokes is always that you take the hit on raw numbers because you trust that special moments are around the corner. That is not a foolish trust; he has proven that to be the case. But it is important that English cricket recognises that they are not backing the favourite here, the thoroughbred with immaculate form – they are backing a hunch, a hope that the guy who has come through before will come through again.

Before the World Cup, Stokes may not put up the numbers that show he’s a top-class T20 player. England may not get chance to build his selection case around facts and proof. Like before, when it comes to Ben Stokes, England might just have to believe.