Richard Tomlinson, author of the biography Amazing Grace: The Man who was WG, debunks some of the myths about the great cricketer.

First published in 2015

First published in 2015

10. Mother of invention?

According to MCC’s official memorial biography, WG’s mother Martha was his main childhood cricket coach. In fact, she played almost no role in his cricketing education. Martha’s inflated position in cricket history was largely due to Nottinghamshire’s George Parr, who claimed she had written a technically knowledgeable letter to him when her son was a boy, praising his back-lift. Parr admitted he had either lost or destroyed this fabled letter, casting doubt on whether it ever existed.

9. He wasn’t always a shamateur

During the early years of his career, the game’s most famous ‘shamateur’ played hardly any high-profile professional cricket. Between his first-class debut in June 1865 and his election to MCC in May 1869, WG appeared only six times for the United South of England XI, his main professional team in the 1870s. He wanted to prove he was a bona fide gentleman to get elected to MCC, his only route to regular first-class fixtures, and once he was admitted – principally to fill the club’s fine new grandstand – his professional commitments sharply increased.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way. Bet on the IPL here. 18+ please gamble responsibly.

8. He wasn’t that greedy

“I did very well out of the tour financially,” recalled William Oscroft, one of seven English professionals to tour Australia in the winter of 1873/74. Oscroft and his teammates are usually portrayed as victims of Grace’s avarice and the £1,500 plus expenses that Grace received for leading the tour was certainly a vast sum compared with the professionals’ contractual fee of £150 plus £20 for “wines, spirits and other liquors”. Yet the pros likely more than doubled their money selling merchandise in Australia, as well as playing additional games for cash. WG certainly neglected the players but “this wretched second-class business”, as one of them called it, was the fault of the main Aussie promoter William Biddle, who was desperate to cut costs.

7. Spofforth was fibbing

According to tradition, the Ashes were born after Grace inflamed the 1882 Oval Test by sneakily running out Australia’s Sam Jones. Fred Spofforth, Australia’s star bowler, stormed into England’s dressing room, and berated Grace for a “full five minutes” as a cheat. Spofforth then bowled Australia to victory, prompting the Sporting Times to write a mock obituary for English cricket.

Trouble is, Grace could not have been in the England dressing room for a “full five minutes” when ‘Spof’ claimed to be giving him the hairdryer treatment. Grace was upstairs, trying in vain to save the life of George Spendlove, a spectator who began vomiting blood just before the interval. It is possible that WG and Spofforth had a fleeting exchange as Grace dashed upstairs to Spendlove. It is equally possible that Spofforth spent a quiet five minutes in the toilet, before returning to the Australian dressing room with his motivational tale.

6. He was never a workhouse doctor …

Contrary to myth, WG was never employed by Bristol’s Eastville workhouse, nor was he a ‘slum’ doctor. The surrounding neighbourhood had its fair share of paupers, but most of Grace’s patients had the money to pay him fees. Grace’s problem was that his patients expected him to be available all year round and resented his long absences playing cricket.

5. … Nor a countryman

Grace was “of pure country strain”, John Arlott once pronounced fruitily. Well, not really. WG counted no one in his family or immediate ancestry who lived off the land; his people were principally doctors and teachers. Nor did Grace display any particular desire to live in the countryside. In 1893, flush with cash from his lucrative second tour of Australia, WG chose to rent a smart town house in Bristol rather than a desirable country residence. Confusion about Grace’s roots arose because of his apparently ‘rustic’ accent (more a Bristol dialect) and lifelong love of ‘country’ sports.

4. He wasn’t a great Test player

At first glance, this seems perversely contrarian. Grace played one indisputably great Test innings of 152 on his debut at the Oval, yet his international career was mostly downhill from there. He scored only one more century in 22 matches and managed just five fifties. He scarcely bowled in Test cricket and his huge bulk made him a liability in the field. Grace’s tragedy was that he peaked in the early 1870s, before the advent of Test cricket, and then wrecked himself physically by overeating and increasingly heavy drinking.

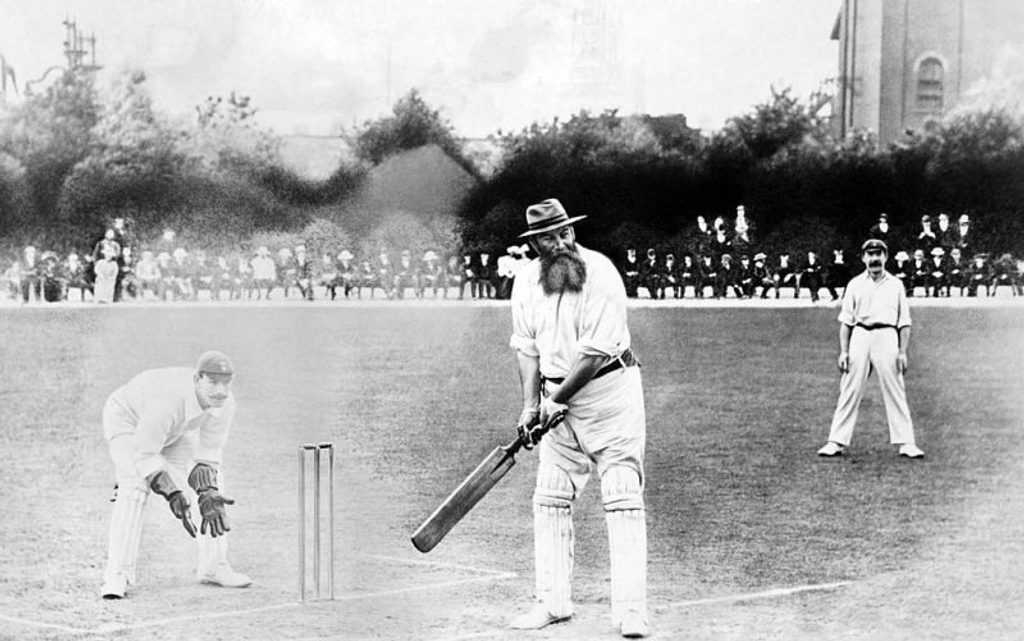

A 56-year-old WG Grace batting for the London County cricket team against Derbyshire at Chesterfield, circa August 1904

A 56-year-old WG Grace batting for the London County cricket team against Derbyshire at Chesterfield, circa August 1904

3. His testimonials nearly flopped

In 1876, early plans for a so-called ‘testimonial’ fund for Grace went off course when the MCC’s sex-crazed secretary Robert Fitzgerald was despatched to a lunatic asylum, suffering from tertiary syphilis. Grace’s second ‘testimonial’ also had a troubled genesis. When Grace scored his 100th first-class century, a Bristol solicitor wrote to the Daily Telegraph, suggesting a national ‘shilling’ fund for WG. Editor John Le Sage was not interested.

It took an intervention from the Prince of Wales to kick-start the fundraising. The future Edward VII instructed his private secretary to write a letter of congratulation to Grace. Grace or someone close to him immediately leaked the letter to the press, prompting Le Sage to change his mind and persuade the Telegraph’s proprietor to launch the newspaper’s ‘National Shilling’ fund. The MCC’s committee bowed to the inevitable and started its own, much smaller fund. Le Sage maintained that the idea had been his all along.

2. He was a book lover and a fine writer

“To my grandchildren Edgar, Bess, Gladys and Prim, who I hope will always love books.” So WG wrote on the front of an Easter present in 1915. When he died, the estate duty-valuer counted about 150 volumes at Grace’s house. Intellectual snobbery underlay the slur that Grace never read a book in his life and couldn’t write grammatical English. As for Grace’s sometimes-ungrammatical handwritten notes, think of them as the Victorian equivalent of email. When Grace set down his thoughts on cricket he used beautifully clear, lucid English that deserves to be read today.

1. He was as good as Bradman

This seems impossible, given Grace’s vastly inferior Test record. But it is a legitimate talking point, especially if you enjoy winding up Aussies (as he did). Consider: by the age of 27, WG had scored 50 first-class centuries. Statistician Irving Rosenwater calculated that you had to add up all the centuries scored by the next 13 most prolific batsmen in the same 10-year period to reach Grace’s tally.

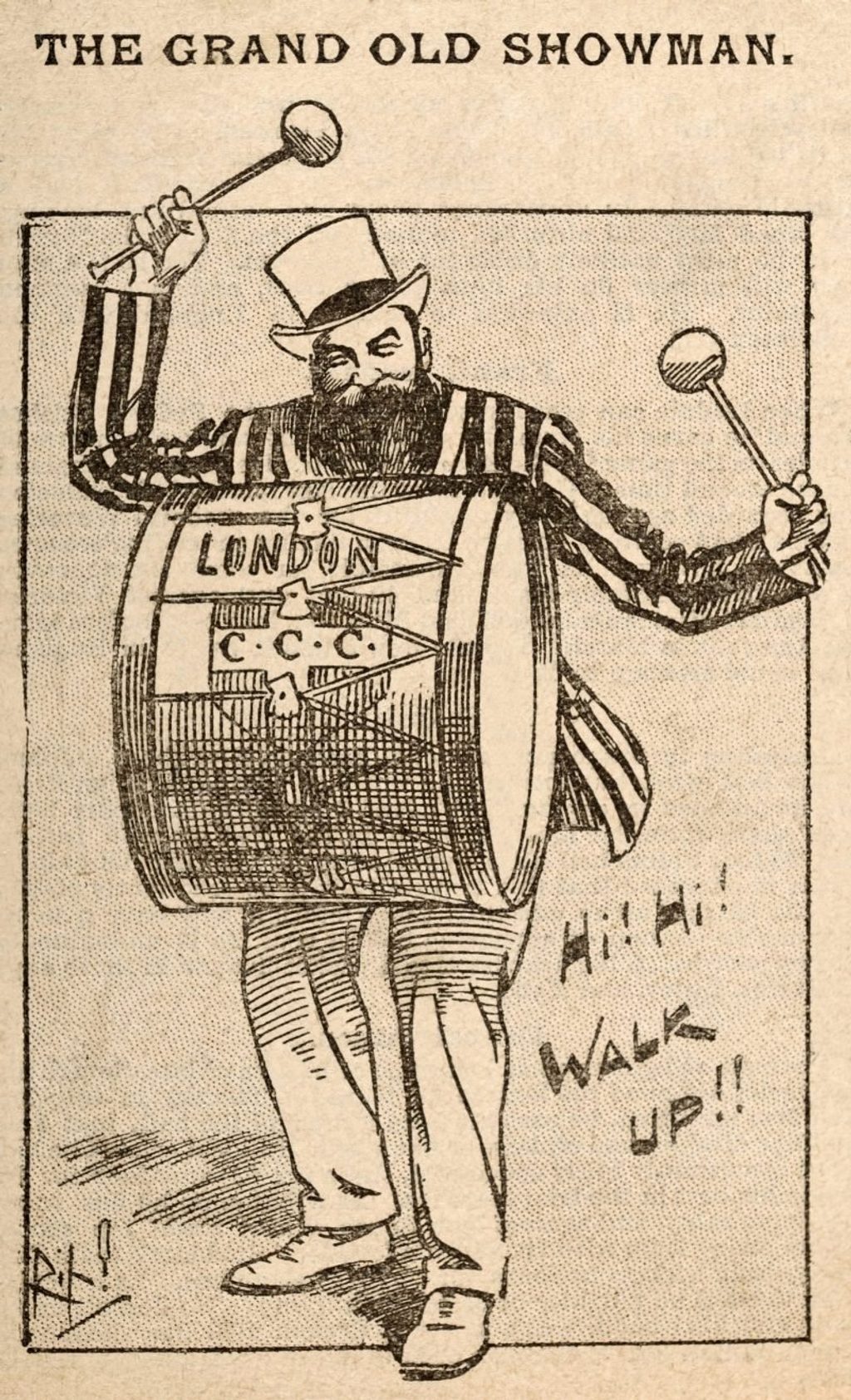

A vintage illustration portraying WG Grace as “The Grand Old Showman” banging on the London CCC bass drum, circa 1885

A vintage illustration portraying WG Grace as “The Grand Old Showman” banging on the London CCC bass drum, circa 1885

When MCC finally admitted Grace in 1869, four years after his first-class debut, he had scored only five first-class centuries. Over the next seven seasons, he scored 45 more, performing this feat at a time when there were no overseas first-class tours and when pitches were sometimes so dangerous that batsmen risked their lives each time they took guard. In 1870 WG scored 117 not out for MCC on a cracked Lord’s wicket against a strong Nottinghamshire attack. In the same match, the Notts batsman George Summers was knocked unconscious by a rising delivery that probably hit a stone. He died of his head injury four days later.

Yes, Bradman did better than any other Australian batsman against Larwood and Voce bowling bodyline; yes, he scored many stupendous centuries against other great bowlers; and of course, Bradman scored far more Test centuries (29) than Grace. Yet the record shows that Bradman scored many of his centuries on flat pitches against bowling attacks that weren’t exactly legendary.

In the absence of film, one will never know exactly how good Grace was. Only this much is certain. WG’s claim to all-time greatness as a batsman rests on a remarkably short period, when he was still a superb athlete rather than the prematurely aged hulk he became.