Curtly Ambrose spearheaded West Indies’ attack for more than a decade, and he was never more destructive than in England in 1991 when his efforts earned a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

Curtly Ambrose played on until 2000, finishing with 405 Test wickets at 20.99

The spectre of the gangling Curtly Ambrose will undoubtedly haunt those batsmen unfortunate enough to confront him in England last season, when the 27-year-old Antiguan carried all before him, and single-handedly almost stilled the nascent Test career of Graeme Hick, a figure so thoroughly disenchanted before the series was complete that the selectors were forced to drop him.

Ambrose has the ability to exert a debilitating psychological influence which so often precipitates a cluster of wickets after the initial breach has been made. It is no fun waiting in the wings, knowing your time is nigh. Hick, as an obvious example, often looked a sentenced man on his way to the crease, and this from a player who usually raced down the pavilion steps in expectation of the plunder to come.

No other explanation exists, either, for that telling passage off the first ball of the fourth Test at Edgbaston, when Graham Gooch sparred at a widish loosener from Ambrose, only for Carl Hooper, uncharacteristically, to put the chance to grass. Surely no other bowler could have provoked such an involuntary response from the England captain.

Ambrose accounted for Hick six times out of seven before England’s new recruit was relieved of duty to undergo a very necessary period of recuperation outside the demanding environment of Test cricket. But in that he was not alone. Others before had had their profile reduced by the 6ft 7in marauder who was born on September 21, 1963 in Swetes, a village in the parched interior of Antigua.

Curtly Elconn Lynwall Ambrose grew up as a natural basketballer and considered migrating to the United States before starting cricket at 17, graduating from beach cricket and umpiring to the parish team. Andy Roberts was an early mentor, emphasising the psychological aspect of bowling and instilling a belief in Ambrose that he could join countrymen Baptiste, Ferris and Benjamin at the highest level.

After an early foray in the West Indies regional competition in 1985/86, when four wickets cost 35 runs apiece, he left an indelible mark on the 1987/88 competition in establishing a record of 35 wickets at only 15.51 during his first full season, thereby erasing Winston Davis’s previous tournament best of 33, which had stood since 1982/83. The West Indian selectors immediately pitched him into Test cricket that April, against Pakistan at Bourda, but it was an inauspicious debut, coinciding with West Indies’ first home defeat for a decade.

In 1986, at Viv Richards’s instigation, Ambrose had summered in England, playing for Chester Boughton Hall in the Liverpool Competition, where he is remembered as “an inveterate late arriver, though he only lived across the road.” The following year he moved to Heywood in the Central Lancashire League, in which he garnered 115 cheap wickets, and in 1988 he was back again, but this time as a member of the West Indian touring team.

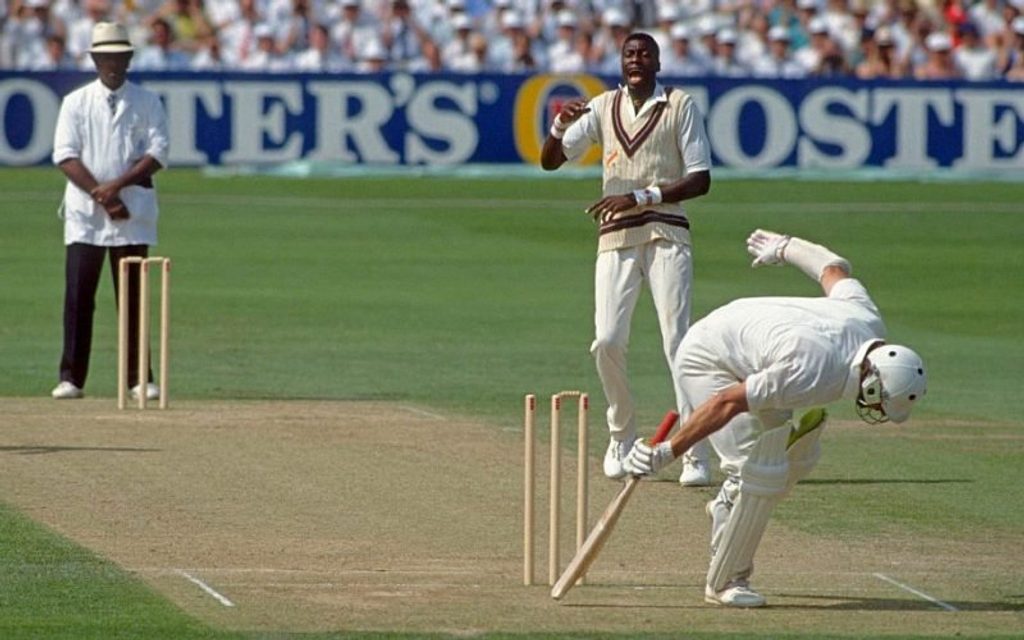

Graeme Hick is cleaned up by Curtly Ambrose at Headingley

Graeme Hick is cleaned up by Curtly Ambrose at Headingley

Extremely shy and retiring, and sometimes lugubrious in his formative years as a cricketer, he never enjoyed the tag of “pro” and has tended towards reclusiveness beneath the ubiquitous Walkman. Yet he occasionally gives evidence of a rare humour. Once asked which was his favourite football team, he replied, “Crown Paints, man!”

If, as his name suggests, he is not quite a Lindwall in terms of the range of his bowling, he does have outright pace and he generates a disconcerting, steepling bounce from fuller-length deliveries. But while he was once no-balled for throwing, by the Trinidadian umpire, Clyde Cumberbatch, in the Leewards’ first match of the 1987/88 Red Stripe Cup, against Trinidad & Tobago at Guaracara Park, Ambrose’s action is unequivocally legal. His height and a slender, sinewy wrist contribute greatly to the final velocity, the wrist snapping forward at the instant of release to impart extra thrust to the ball’s downward trajectory.

Michael Holding had this vital asset, and Courtney Walsh’s wrist action, too, has given rise to notions of illegal delivery. Never a great swinger of the ball, he compensates with a smooth, leggy run-up, fast arm action and accuracy. Like Joel Garner, he possesses a lethal yorker and a nasty bouncer, but his career-best eight for 45 against hapless England at Bridgetown in 1990 owed everything to the virtues of speed and straightness. Five victims were lbw, pinned to their stumps as Ambrose squared a series England had waged so gallantly until then.

Jeffrey Dujon’s station has allowed him a unique insight into the relative merits of the phalanx of West Indies quicks over the years, and in his assessment Holding was undeniably the fastest, while Roberts, an introvert and a deep thinker, was capable of delivering two different bouncers with no discernible change in action. “Wonderful control was the essence, and the faster one shocked some very good batsmen,” Dujon affirms.

He reserves special affection, too, for the relatively inexperienced Ambrose, who he reckons has the credentials to take his place among the greats. “He is mature beyond his years, has pace, accuracy, heart and determination, plus, importantly, real pride in economical figures.”

The crucial question now is for how long a spindly frame can withstand the rigours of Test-match bowling. Ambrose has spearheaded West Indies’ attack for four years, and Richards, his captain, has already demanded a considerable workload; yet his appetite for the game and that keen concern for the economy rate have remained undimmed. His consistency has become a byword since the 1988 tour of England, his first, which produced 22 Test wickets at cost 20.22.

Ambrose has Botham tumbling over his stumps at The Oval – the latter’s only hit-wicket dismissal in international cricket

Ambrose has Botham tumbling over his stumps at The Oval – the latter’s only hit-wicket dismissal in international cricket

In Australia in 1988/89 he was the most outstanding performer with 26 wickets at 21.46, and last summer against England his 28 wickets cost 20 apiece. Moreover, he was arguably the essential difference between the two sides in what proved to be a zestful series.

Assuredly, not many batsmen will relish another confrontation, but they have at least been granted some respite. West Indies’ next full series is not until the winter of 1992/93, in Australia, when “Amby” will be looking to improve on an outstanding Test record of 140 wickets at 23.14. By then, he will have entered the peak years for a bowler of his type, 28 to 32, still with only five years of international cricket behind him. It is an awesome prospect.