Of all the battery of fast bowlers produced by West Indies in the 1970s and 1980s, Malcolm Marshall was the greatest. His death in 1999 stunned the cricket world.

Marshall, Malcolm Denzil, died on November 4, 1999, aged 41.

Malcolm Marshall was one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time. Even in the formidable line-up of West Indians whose speed and ferocity dominated world cricket for the last quarter of the 20th century, Marshall stood out: he allied sheer pace to consistent excellence for longer than anyone else; he was relentlessly professional and determined; and he was also the best batsman of the group, coming nearer than any recent West Indian to being an all-rounder of the quality of Garry Sobers. Though batsmen feared him, he was exceptionally popular among his peers: his death was mourned throughout the cricket world, but his fellow-professionals, who knew him best, were most deeply affected.

Marshall was born in St Michael, Barbados. As with Sobers, his triumphs grew out of childhood tragedy: his father was killed in a road accident when he was a baby, and he learned the game from his grandfather as well as at the beach and the playground. He began as a batsman, then discovered his ability to strike back. After playing just one first-class match for Barbados as a 19-year-old, he was taken to India amid the confusion of the World Series schism in the weakened team captained by Alvin Kallicharran.

He made his Test debut, aged 20, in December 1978 at Bangalore. Marshall made no immediate impact at that level but showed enough to be taken on by Hampshire as successor to Andy Roberts. He missed part of the 1979 season because of the World Cup. But, with West Indies back to full strength, he could not get on the field for them; on the team picture, standing next to Joel Garner and Colin Croft, he looks an insignificant figure. In county cricket, meanwhile, he did not yet have the firepower to carry a struggling team.

However, on the 1980 tour he secured a Test place and at Manchester was instrumental in causing a collapse of seven wickets for 24. It began to be noted that, although not physically imposing – he was 5ft 11in – he had a natural balance and athleticism. Furthermore, he applied himself to his craft. In 1982, he was devastating, taking 134 wickets for Hampshire – a figure no one else touched in county cricket in the last 32 years of the century – and building a reputation as the bowler best avoided by anyone with a sense of self-preservation.

Careful observers noted that he also bowled more Championship overs than anyone else. His first really dominant Test performance came at Port-of-Spain the following March, when he took five for 37 against India. When West Indies played Pakistan in the 1983 World Cup semi-final at The Oval, he worked up top speed even in a one-day game, and it was obvious – though he was still first-change – that the global fast-bowling crown now rested on his head.

And there it stayed. Batsmen agreed that Marshall was hardest of all to face because of the way he used his ordinary height to produce telling rather than exceptional bounce. He was, they said, a skiddy bowler. His out-swinger was magnificently controlled. And when he dropped short of a length – he was never shy of doing that – especially from round the wicket, he produced deliveries that were as physically intimidating as anything the game has seen.

In 1983/84 he was the prime avenger for the World Cup final defeat by India, taking 33 wickets in a six-Test series which West Indies won 3-0. Less than four months later, he overpowered Australia’s batsmen, taking five for 42 when they were 97 all out at Bridgetown, and five for 51 at Kingston. But it was at Headingley in July 1984 that he produced his most astonishing performance: on the first day, he broke his left thumb in the field and was assumed to be out of the game. When the ninth West Indian first-innings wicket fell, the England players were about to stroll off. Suddenly, Marshall marched down the dressing-room steps and batted one-handed long enough for Larry Gomes to score a century. Then, with his lower arm encased in pink plaster, Marshall took seven for 53: bowling first at his normal pace, then swinging the ball in the heavy northern air, throughout showing an indomitable ability to play through pain that in itself helped force England into submission. He recovered from the injury to blast England out with a fusillade of bouncers at The Oval: his seventh five-for in ten Tests, a sequence he took to 11 in 14 a few months later when he took command of the series in Australia.

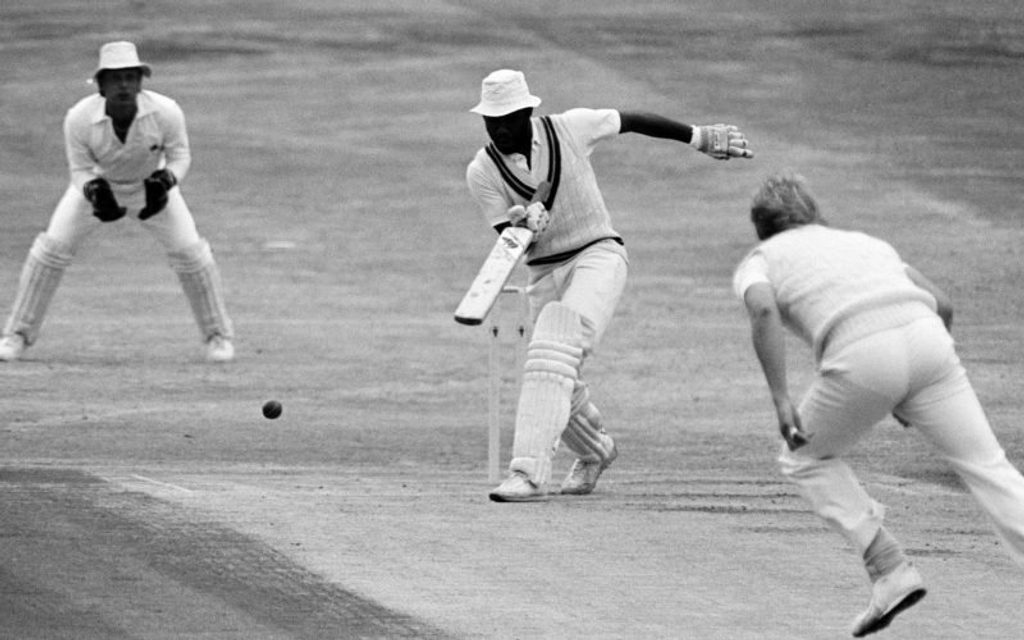

The unbreakable spirit – Malcolm Marshall batting one-handed at Headingley

The unbreakable spirit – Malcolm Marshall batting one-handed at Headingley

At this point, Marshall was in his unbeatable prime. He set the tone for the 1985/86 series against England by breaking Mike Gatting’s nose in a one-day international, just as he had done when he hit Andy Lloyd (who never recovered as a top-level cricketer) at the start of the 1984 series. And he led an assault on the New Zealand batsmen at Kingston in 1984/85 that may well have been the most intimidatory of the lot. No umpire in the world – and certainly none in the West Indies – had the courage to limit properly the number of bouncers.

But venom was only part of his armoury. Marshall acquired ringcraft at an early stage: he developed the in-swinger and the leg-cutter. And he became capable of playing vital Test innings as well, at No.8 or even higher (he made 92 against India in 1983/84, and scored seven first-class centuries) without ever quite losing his fast bowler’s relish in batting as a hobby. He produced another commanding performance with the ball at Lahore in 1986/87, and against the England rabble of 1988 took 35 wickets at just 12.65. Five of them came in an hour at Old Trafford where he finished with seven for 22 and England were 93 all out.

He rarely bowled a bouncer in that series; there was no real need. But in the report of the Old Trafford game Wisden noted the progress of the unknown Ambrose at the other end. Batsmen never threatened Marshall’s dominance but soon after West Indian bowlers did. He had another blazing match (11 for 89) against India at Port-of-Spain in 1988/89, but more often he was one of the pack, and he played his 81st and final at The Oval in 1991, where Graham Gooch became his 376th Test victim. This remained a West Indian record until Walsh overtook him in 1998/99. But Marshall’s average of 20.94 is unsurpassed by any bowler who has taken 200 Test wickets.

Marshall continued playing for Hampshire for the next two seasons, and was thrilled to bits when they won the 1992 Benson and Hedges final. He returned to the club as coach in 1996, emphasising that this was not the ordinary businesslike relationship that exists between a county and an overseas pro. He became West Indies’ coach that year too, though by the time he was taken ill during the 1999 World Cup, Marshall was inevitably taking his share of the blame for the team’s inability to live up to the standards he had himself helped to set. The fact that both his old teams wished to employ him was a testament to the esteem in which he was held. He was diagnosed with cancer of the colon in the spring of 1999. Chemotherapy in England failed, and he went home to Barbados, marrying his girlfriend Connie a few weeks before he died.

It was his willingness to work hard at his game that made Malcolm Marshall supreme even in a great generation. He was a relentlessly probing and thoughtful opponent – his Hampshire team-mate Robin Smith said he could nominate the deliveries that would get players out. And, to an extent matched only by the slightly more sedate Walsh, he was willing to produce his best on dull days and dull pitches when other overseas players might lay off the accelerator.

After play, he was affable among his fellow-pros and polite to all-comers. He was contemptuous of his West Indian contemporaries who went to South Africa to bolster apartheid in 1982/83 but, when the politics changed in the 1990s, he went to play and coach in Natal, where he became as revered as in Southampton or Bridgetown. Across the continents, to a generation of cricketers unused to the death of their friends, the loss of Marshall came as a savage blow. Five West Indian captains were among the pallbearers.