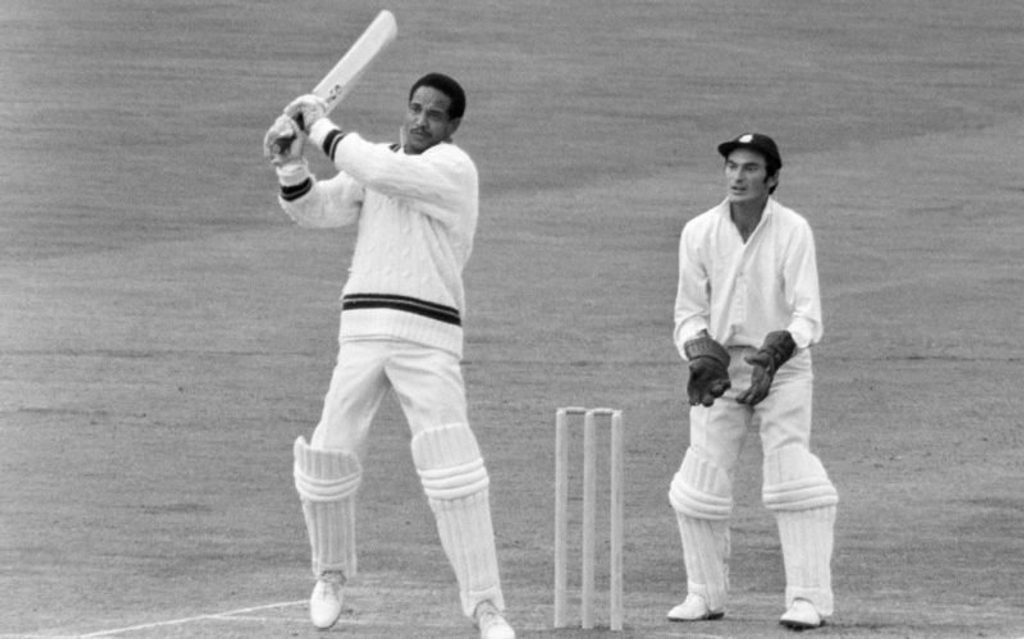

After a long career of extraordinary achievements and countless hours of entertainment, Sir Garfield Sobers retired in 1974. The following year’s Wisden Almanack paid this tribute.

Sir Garfield Sobers, the finest all-round player in the history of cricket, has announced his retirement from full time county cricket at the age of 38. Circumstances seem to suggest he will not be seen again in Test matches. He was not with West Indies on their recent tour of India and Pakistan; and they have no other international commitment until 1976, when their full-length tour of England might well prove too physically trying for a 40-year old Sobers, most deservedly given a knighthood in the New Year Honours.

So it is likely that international cricket has seen the last of its most versatile performer. For 20 years – plus, to be precise, seven days – he served and graced West Indian cricket in almost every capacity. To review his career compels so many statistics as might mask the splendidly exciting quality of his play. Nevertheless, since many of his figures are, quite literally, unequalled, they must be quoted.

Between March 30, 1954 and April 5, 1974, for West Indies, he appeared in 93 Tests – more than any other overseas cricketer: he played the highest Test innings – 365 not out against Pakistan at Kingston in 1958; scored the highest individual aggregate of runs in Test matches; and captained his country a record 39 times. His 110 catches and – except for a left hander – his 235 wickets are not unique: but his talents in those directions alone justified a Test place. I quote his West Indies figures.

Garfield Sobers was 17 when he first played for West Indies – primarily as an orthodox slow left arm bowler (four for 81), though he scored 40 runs for once out in a losing side. His batting developed more rapidly than his bowling and, in the 1957/58 series with Pakistan in West Indies, he played six consecutive innings of over fifty the last three of them centuries.

Through the sixties he developed left-arm wrist-spin, turning the ball sharply and concealing his googly well. Outstandingly, however, at the need of his perceptive captain, Sir Frank Worrell, he made himself a Test-class fast medium bowler. Out of his instinctive athleticism he evolved an ideally economic action, coupling life from the pitch with late movement through the air and, frequently, off the seam. Nothing in all his cricket was more impressive than his ability to switch from one bowling style to another with instant control.

Sir Garfield Sobers had a Test batting average of 57.78 – the highest among batsmen with a minimum of 8,000 Test runs

Sir Garfield Sobers had a Test batting average of 57.78 – the highest among batsmen with a minimum of 8,000 Test runs

He was always capable of bowling orthodox left arm accurately, with a surprising faster ball and as much turn as the pitch would allow a finger spinner. He had, though, an innate urge to attack, which was his fundamental reason for taking up the less economical but often more penetrative wrong’un, and the pace bowling which enabled him to make such hostile use of the new ball.

As a fieldsman he is remembered chiefly for his work at slip – where he made catching look absurdly simple – or at short leg where he splendidly reinforced the off-spin of Lance Gibbs. Few recall that as a young man he was extremely fast – and had a fine arm – in the deep, and that he could look like a specialist at cover point.

Everything he did was marked by a natural grace, apparent at first sight. As he walked out to bat, 6ft tall, lithe but with adequately wide shoulders, he moved with long strides which, even when he was hurrying, had an air of laziness, the hip joints rippling like those of a great cat. He was, it seems, born with basic orthodoxy in batting; the fundamental reason for his high scoring lay in the corrections of his defence. Once he was established (and he did not always settle in quickly), his sharp eye, early assessment, and inborn gift of timing, enabled him to play almost any stroke.

Neither a back-foot nor a front-foot player, he was either as the ball and conditions demanded. When he stepped out and drove it was with a full flow of the bat and a complete follow through, in the classical manner. When he could not get to the pitch of the ball, he would go back, wait – as it sometimes seemed, impossibly long – until he identified it and then, at the slightest opportunity, with an explosive whip of the wrists, hit it with immense power. His quick reactions and natural ability linked with his attacking instinct made him a brilliant improviser of strokes. When he was on the kill it was all but impossible to bowl to him – and he was one of the most thrilling of all batsmen to watch.

Crucially, Sir Garfield Sobers was not merely extremely gifted, but a highly combative player. That was apparent on his first tour of England, under John Goddard in 1957. Too many members of that team lost appetite for the fight as England took the five-match rubber by three to none. Sobers, however, remained resistant to the end. He was a junior member of the side – his 21st birthday fell during the tour – but he batted with immense concentration and determination.

He was only twice out cheaply in Tests: in two Worrell took him in to open the batting and, convincingly, in the rout at The Oval, he was top scorer in each West Indies innings. He was third in the Test batting averages of that series which marked his accession to technical and temperament maturity.

The classic example of his competitive quality was the Lord’s Test of 1966 when West Indies, with five second innings wickets left, were only nine in front and Holford – a raw cricketer but their last remaining batting hope – came in to join his cousin Sobers. From the edge of defeat, they set a new West Indies Test record of 274 for the sixth wicket and, so far from losing, made a strong attempt to win the match.

Sir Garfield Sobers took 235 Test wickets at 34.03 and was the first player to achieve a triple of 5,000 runs, 200 wickets and 100 catches in Test cricket

Sir Garfield Sobers took 235 Test wickets at 34.03 and was the first player to achieve a triple of 5,000 runs, 200 wickets and 100 catches in Test cricket

Again, at Kingston in 1967/68, West Indies followed on against England and, with five second innings wickets down, still needed 29 to avoid an innings defeat. Sobers – who fell for a duck in the first innings – was left with only tail-enders for support yet, on an unreliable pitch, he made 113 – the highest score of the match – and then, taking the first two English wickets for no runs, almost carried West Indies to a win.

For many years, despite the presence of some other handsome stroke-makers in the side, West Indies placed heavy reliance on his batting, especially when a game was running against them. Against England 1959/60 and Australia 1964/65, West Indies lost the one Test in each series when Sobers failed. His effectiveness can be measured by the fact that in his 93 Tests for West Indies he scored 26 centuries, and fifties in 30 other innings; four times – twice against England – averaged over one hundred for a complete series; and had an overall average of 57.78. There is a case, too, that he played a crucial part as a bowler in winning at least a dozen Tests.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JGdMKWZi7A

To add captaincy to his batting, different styles of bowling and close fielding may have been the final burden that brought his Test career to an early end. He was a generally sound, if orthodox, tactician but after 39 matches as skipper, the strain undoubtedly proved wearing. In everyday life he enjoys gambling and, as a Test captain, he is still remembered for taking a chance which failed.

It occurred in the 1967/68 series against England, when he made more runs at a higher average – and bowled more overs than anyone else except Gibbs – on either side. After high scores by England, the first three Tests were drawn, but in the fourth, after Butcher surprisingly had bowled out England in their first innings with leg spin, Sobers made a challenging declaration. Butcher could not repeat his performance and Boycott and Cowdrey skilfully paced England to a win. Thereupon the very critics who constantly bemoaned the fact that Test match captains were afraid to take a chance castigated Sobers for doing so – and losing. The epilogue to that failure was memorable. With characteristic confidence in his own ability, he set out to win the fifth Test and square the rubber. He scored 152 and 95 not out, took three for 72 in the first England innings and three for 53 in the second – only to fall short of winning by one wicket with a hundred runs in hand.

Sir Garfield Sobers held the record of highest individual score in Tests – 365*, for more than three decades, until he was surpassed by Brian Lara in 1994

Sir Garfield Sobers held the record of highest individual score in Tests – 365*, for more than three decades, until he was surpassed by Brian Lara in 1994

Students of sporting psychology will long ponder the causes of Sobers’ retirement. Why did this admirably equipped, well rewarded and single-minded cricketer limp out of the top level game which had brought him such eminence and success? He was only 38: some great players of the past continued appreciably longer. Simply enough, mentally and physically tired, he had lost his zest for the sport which had been his life – and was still his only observable means of earning a living.

Ostensibly he had a damaged knee; in truth he was the victim of his unique range of talents – and the jet age. Because he was capable of doing so much, he was asked to do it too frequently. He did more than any other cricketer, and did it more concentratedly because high speed aircraft enabled him to travel half across the world in a day or two. Perhaps the long sea voyages between seasons of old had a restorative effect.

In a historically sapping career, Sobers has played for Barbados for 21 seasons; in English league cricket for eight, for South Australia in the Sheffield Shield for three, and Nottinghamshire for seven; he turned out regularly for the Cavaliers on Sundays for several years before there was a Sunday League in England; made nine tours for West Indies, two with Rest of the World sides and several in lesser teams; 89 of his 93 Tests for the West Indies were consecutive and he averaged more than four a year for 20 years. There is no doubt, also, that his car accident in which Collie Smith was killed affected him more profoundly and for longer than most people realised.

The wonder was not that the spark grew dim but that it endured so bright for so long. Though it happened so frequently and for so many years, it was always thrilling even to see Sobers come to the wicket. As lately as 1968 he hit six sixes from a six ball over. In 1974 on his farewell circuit of England he still, from time to time, recaptured his former glory, playing a lordly stroke or making the ball leave the pitch faster than the batsman believed possible.

As he walked away afterwards, though, his step dragged. He was a weary man – as his unparalleled results do not merely justify, but demand. Anyone who ever matches Garfield Sobers’ performances will have to be an extremely strong man – and he, too, will be weary.

An amazing man, he still insists, “As long as I am fit and the West Indies need me, I will be willing to play for them.” Only time will tell if we shall see him in the Test arena again. In October last he joined the executive staff of National Continental Corporation to promote the company’s products in the Caribbean and United Kingdom.

And now he has joined his lamented compatriots Sir Learie Constantine and Sir Frank Worrell with the title Sir Garfield Sobers.