Charlie Griffith was West Indies’ leading bowler during their 1963 tour of England with a staggering 119 wickets – 32 of which came in their 3-1 Test series win. He was named a Wisden Cricketer of the Year the following spring.

Charlie Griffith couldn’t quite carry his brilliance at the Test level after 1963, and finished with 94 wickets from 28 Tests. In 96 first-class games, he took 332 wickets at 21.60.

English cricket received due warning at Bridgetown, Barbados, on New Year’s Eve, 1959, that Charles Christopher Griffith had arrived. At 21 years of age, in his first-class debut, he dismissed MC Cowdrey, MJK Smith and PBH May in two overs.

The following day KF Barrington was added to his formidable list of victims and in the second innings Smith again and ER Dexter tasted a further sample of things to come.

To claim the wickets of three England captains was a feat of which Griffith or any young bowler could feel justly proud. Indeed, that initial burst of success rates still as Griffith’s finest hour, the event of a short career which gives him the greatest thrill.

So Griffith started life in first-class cricket as he intended to continue, by matching his skill and intelligence against the best batsmen in the world – and emerging triumphant. He did so with great regularity in England last summer, finishing the tour as West Indies leading bowler with 119 wickets at an average of 12.83 each. With Hall, he shared an opening attack which ranks now as one of the finest and fastest of all time.

The game has been well served by pace bowling partners – Barnes and Foster, Larwood and Voce, Tyson and Statham, Trueman and Statham of England, Gregory and McDonald, Lindwall and Miller of Australia. Now Griffith and Hall join their fellow West Indians Constantine and Martindale among the best of them.

Charles Griffith hails from Barbados, that sceptred isle which in modern times has produced men like FM Worrell – the finest captain in the world, says Griffith – ED Weekes, CL Walcott, and GS Sobers. He was born at St. Lucy, a small sugar-growing community eighteen miles north of Bridgetown, on December 14, 1938. One of eight children – five brothers and two sisters – he took an immediate interest in cricket when starting his education at St. Clement’s Boy’s School, St. Lucy, at the age of five.

No member of his family played with any proficiency before him and there was no one to give Griffith special coaching. It was as a wicket-keeper-batsman that he first showed promise. The youngest member of his school side, he was also the best and Griffith established in those early days a love for batting which he still holds dear today.

He left school at 15 and spent two years with Crickland Cricket Club before joining Windsor where he came out from behind the stumps to begin his career as a bowler. Off-spin was his stock in trade and it brought him moderate rewards but nothing which Griffith can recall with great enthusiasm.

It was a different story when he joined his third Barbadian club, Lancashire. He went as an orthodox spinner but found the side without a fast bowler. The willing young Griffith volunteered to fill the breach and vividly remembers the day he took seven wickets for one run with his new mode of attack.

In his first season with Lancashire, when still only 19, he claimed seventy-three wickets, including a hat-trick. His next and present club was Empire, a side which boasts members of the calibre of Weekes, CC Hunte and SM Nurse, and it was this move which put Griffith on the road to fame. For Weekes, one of the greatest of all West Indies batsmen, also knew sufficient about bowling to spot the talent which Griffith possessed and pass on tips which proved of infinite value.

So quickly did the prodigy develop that, in his first season with Empire, Griffith caught the eye of the Barbadian selectors and was plunged into big cricket when MCC began the 1959/60 tour. Their faith was justified.

Griffith, on that memorable occasion, had figures of four for 64 and two for 66 as his contribution to a ten-wickets victory, but it was not until the fifth Test of the series at Port of Spain that he won international recognition and shared the new ball with Hall, the bowler he considers the best and fastest in cricket today.

In this match, too, Griffith made a favourable beginning. He dismissed GA Pullar, caught at second slip by Sobers, with only 19 on the board, but then faded disappointingly. To quote his own words, he was not a success. Griffith in fact did not play in another Test match until he came to England in 1963.

He began the tour as a bowler of whom English followers knew comparatively little. Hall was rated the No. 1 attacker and King, with whom Griffith shared hotel rooms throughout the tour, was considered his likely opening partner. But Griffith was an early success with eight for 23 and five for 35 against Gloucestershire at Bristol and five for 37 against the Champions at Middlesbrough and became an automatic choice for the Tests.

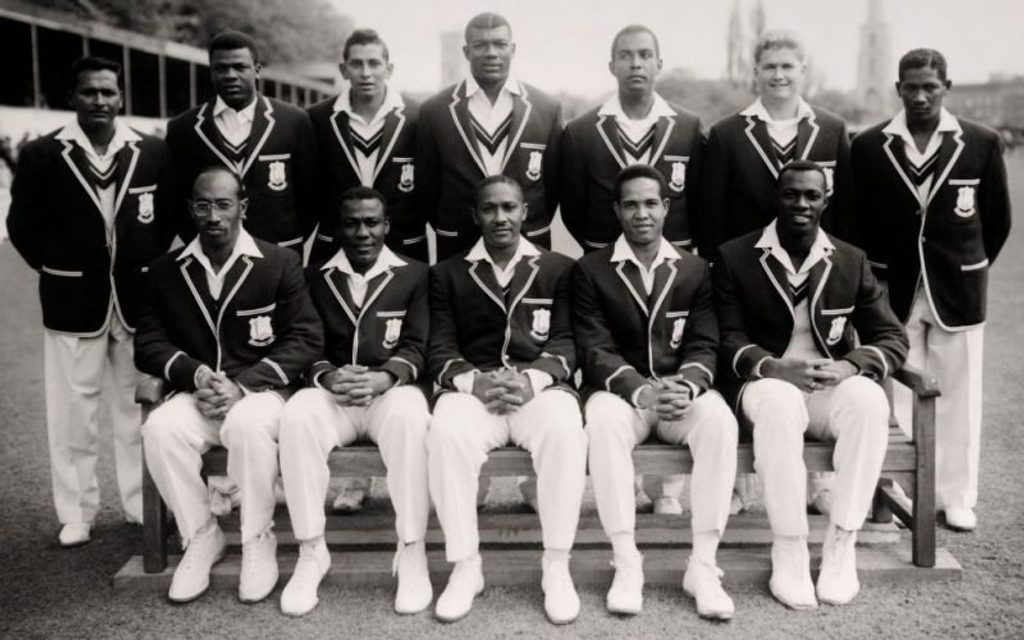

The West Indies team at Worcester, May 1963

The West Indies team at Worcester, May 1963

His deadly yorker – “I can produce it at will” – proved virtually unplayable and he finished the tour with 37 more wickets than Sobers, the next most successful West Indian bowler.

Life has not always been so sweet for Griffith who works as a clerk for the Barbados Transport Board when he is not playing cricket. The incident in which he was involved during the tour by India to the West Indies in 1962 still ranks as one of the blackest in the game.

NJ Contractor, the Indian captain, playing against Barbados, was hit on the temple by a ball from Griffith and taken to hospital with a fractured skull. The fight for his life, which lasted several days, was successful but his cricket career was cut short. That Bridgetown tragedy of March, 1962, is one about which Griffith, not unnaturally, does not like to talk.

This was not a happy match for the deeply sensitive Griffith. While the Island’s leading surgeons were fighting for Contractor’s life, Griffith was no-balled as a thrower for the first and only time in his life. Griffith, convinced nothing was wrong with his action, consequently took no steps to put it right and has met with no further reproach in the shape of being no-balled again.

Griffith, six foot two inches tall, of massive build and powerful legs, is a bachelor. He does not smoke and takes only the occasional drink, owing his superb fitness to clean living and vigorous exercise. He contributes his success to concentration, dedication and the seriousness with which he plays.

Only as a batsman does Griffith allow himself the luxury of a smile. When thundering along his 20-yard run to the wicket, Griffith is a determined man who regards the occasional bouncer as a legitimate weapon of the pace bowler’s armoury and uses it not to intimidate batsmen but to dismiss them.

Griffith has never tried to develop his style on that of any other great cricketer. Although a boyhood worshipper of Lindwall and Miller, he has always tried to remain an individual, learning from others but never copying.

Griffith exceeded his wildest dreams in England last year, but confesses that he still has much to learn. That is why he is returning in 1964, having signed a two-year contract as professional to Burnley in the Lancashire League. Charles Griffith, then, is visiting again the country he loves so much, the country in which he refuses to believe the sun ever shines for an entire day.