West Indies’ sensational impact on their 1950 England tour meant that four of them were Wisden Cricketers of the Year the following spring. Frank Worrell was one of them.

Frank Worrell continued to be one of the leading batsmen in world cricket in the 1950s. In 51 Tests, he hit 3,860 runs at 49.48 with nine hundreds. But his greatest impact came as West Indies’ first black captain.

Few, if any, eminent cricketers can view the game with such a detached attitude as the slim, lithely built Frank Maglinne Worrell, one of the most prominent members of the 1950 West Indies touring team. To him, a match, be it Test or club fixture, is just another game of cricket to be enjoyed. Furthermore, he never reads the sports columns in the newspapers, so that he is unaffected by the opinions, favourable or adverse, of the critics.

Born on August 1, 1924, in Barbados, he comes of a non-cricketing family. His father took no more than a passing interest in cricket, and the only relative to achieve even minor distinction at the game was his elder brother, who was in the second XI at school. Frank Worrell proved the exception. He cannot recall when he first handled a bat or ball, but certainly it was at a very early age.

Never coached, he at no time engaged in arduous practice. Nor, as one to whom cricketing ability was a gift of nature, was this ever necessary; but he modelled himself upon the youngest of all Test debutants – JED Sealy, a master at his school, who played 11 times for the West Indies. Worrell’s maxim is that if he makes a mistake in one innings he endeavours to rectify it in the next.

At Combermere School, which he attended till 19, success came early, for he played in the highest class of cricket in the island at the age of 12, representing Barbados at Bridgetown in 1942, when he dismissed five Trinidad batsmen in an innings for 47 runs. Primarily a slow left-arm bowler, he distinguished himself when 14 by taking seven wickets for 18 runs against Harrison College, and for years he occupied one of the last three places in the batting order. From this it may be deduced that his capabilities as a run-getter were, to say the least, regarded lightly.

Chance provided the opportunity which led to him becoming one of the foremost batsmen in present-day cricket. Towards the close of the day in a match for Barbados against Trinidad in 1943, he was sent in upon the fall of the second wicket as nightwatchman to play out time and avoid the possible sacrifice of the wicket of a more reputable batsman.

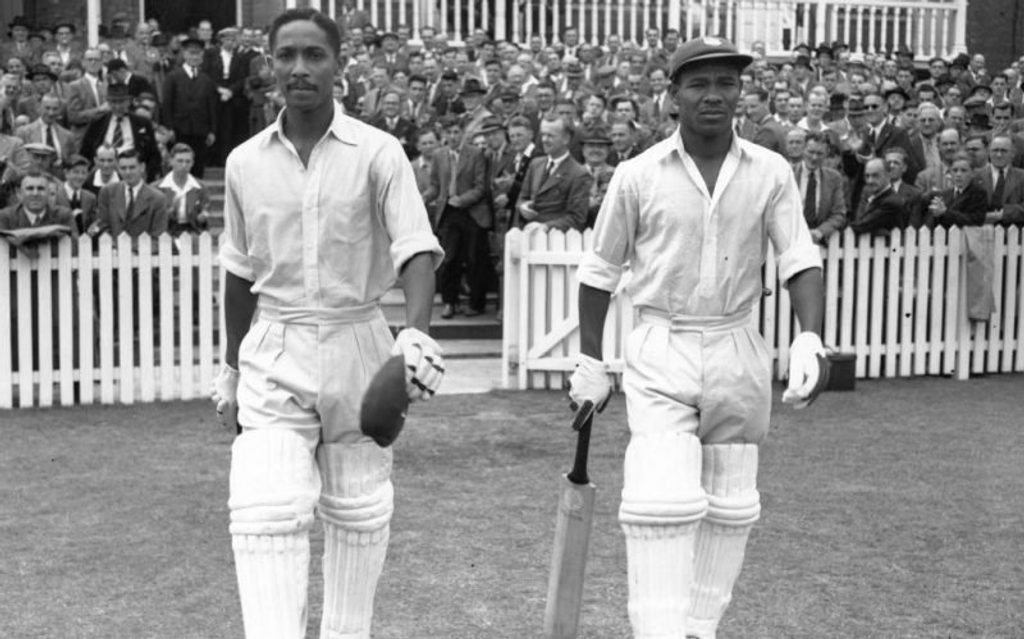

Frank Worrell (left), and Everton Weekes walk out to resume their record-making innings at Trent Bridge

Frank Worrell (left), and Everton Weekes walk out to resume their record-making innings at Trent Bridge

To the surprise of his colleagues, he took out his bat for 64, a performance which warranted his continued promotion in the batting list. In the second meeting with Trinidad in the same month he hit 188 and 68, and thenceforward he did not look back. Next season he placed his name among the record-holders when, for Barbados against Trinidad at Bridgetown, he and John Goddard (218 not out) shared in an unbroken partnership of 502. This was a world’s record for the fourth wicket, and Worrell’s innings of 308 not out remains his highest in first-class cricket.

In 1946, this time with Clyde Walcott (314 not out) as partner, Worrell (255 not out) again inflicted dire punishment upon the luckless Trinidad bowlers, the pair making 574 without being parted, and so raising the fourth-wicket figures still higher. This is no longer a world’s record, for the following year, at Baroda, Vijay Hazare and Gul Mahomed did even better by adding 577, but one cannot trace a parallel instance of a batsman taking part in two stands of over 500.

At times a little uncertain at the start of an innings, he is, when set, most difficult to dismiss, and elegant style, command of every orthodox stroke and perfection of timing make him a delight to watch. He fully demonstrated his skill against GO Allen’s MCC team in the West Indies in 1947/48, when he headed the Test averages with 147 and failed by only three runs to hit a century in the first of his three Tests of that tour. In eight innings against the MCC side he made 472 runs, average 118.

After that he became a professional with Radcliffe, the Central Lancashire League club, for whom in his first season he scored 1,501 runs – a League record – average 88.29, and took 66 wickets. In the 1949/50 winter he toured India with the Commonwealth team and, with 684 runs in nine innings, average 97.71, topped the unofficial Test batting figures. In all matches on that tour he made 1,640 runs, including five centuries, for an average of 74.54. Radcliffe released him for last season’s West Indies visit, and once again he headed the Test batting list. Scoring 539, average 89.83, he brought his average for ten consecutive Test innings against England to 104.12.

The ‘Three Ws’: Worrell (left), Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott at the West Indian Club, London, circa April 1957

The ‘Three Ws’: Worrell (left), Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott at the West Indian Club, London, circa April 1957

He took part in the creation of some new records. His 261 in the third Test at Nottingham was the highest ever hit in a Test at Trent Bridge, and the biggest by a batsman on either side in an England v West Indies game in England. His stand of 283 with Weekes in that match was not only a record for any wicket by either team in the history of the Test series, but for the fourth West Indies wicket in any part of the world.

Again in partnership with Weekes, he set up a record at Cambridge, their 350 against the University being the biggest stand for the third West Indies wicket in England and helping substantially towards the largest total (730 for three wickets) by a team from the Islands in England.

With his advance as a batsman, Worrell was called upon rather less as a bowler, but by varying his style to fast-medium he accomplished some valuable performances last season. Notable among these was his feat in taking two of the first four England wickets at Nottingham and precipitating a collapse; and in the second meeting with Yorkshire his employment of leg-theory did much to turn the scale in a close struggle in favour of his side.

No sooner had the tour of England ended than this seemingly tireless, non-smoking cricketer was away to India again with the Commonwealth team as vice-captain.