Will Smith, Jamie Ellis and Richard Dawson revisit the worst England tours ever – from Ashes drubbings to West Indies annihilation.

First published in 2008

First published in 2008

10. Australia 2002/03

Former England off-spinner Richard Dawson remembers …

When I first set foot on the Perth runway at the start of the 2002 Ashes as a wide eyed 22-year-old, I never expected to play such big a part in what turned out to be another drubbing at the hands of Australia.

Ashley Giles got struck on the wrist in the nets, breaking it. This meant I was called in to the Test team for the final four matches. It’s what you dream about as a young lad. Was I nervous? Christ yes! But what an experience. The crowds, the buzz in the streets, the Barmy Army, going up against cricketing greats: I knew I was involved in something special.

Has a decision to bowl after winning a toss ever been given so much publicity? From the moment Nasser said, “We’ll have a bowl” in the first Test at Brisbane, the cricketing gods seemed to be against us. We lost by the small margin of 384 runs, blown away for 79 in 127 minutes in the fourth dig.

Yes, an unbelievable batting line-up, with Hayden, Langer, Ponting, Martyn, Waugh and Gilchrist pulling the strings, outplayed us. But losing Simon Jones on the first day of the series to a serious knee injury was desperately deflating. In all, we either carried or suffered injuries to Jones, Giles, Gough, Silverwood, Hussain, White, Tudor and Stewart.

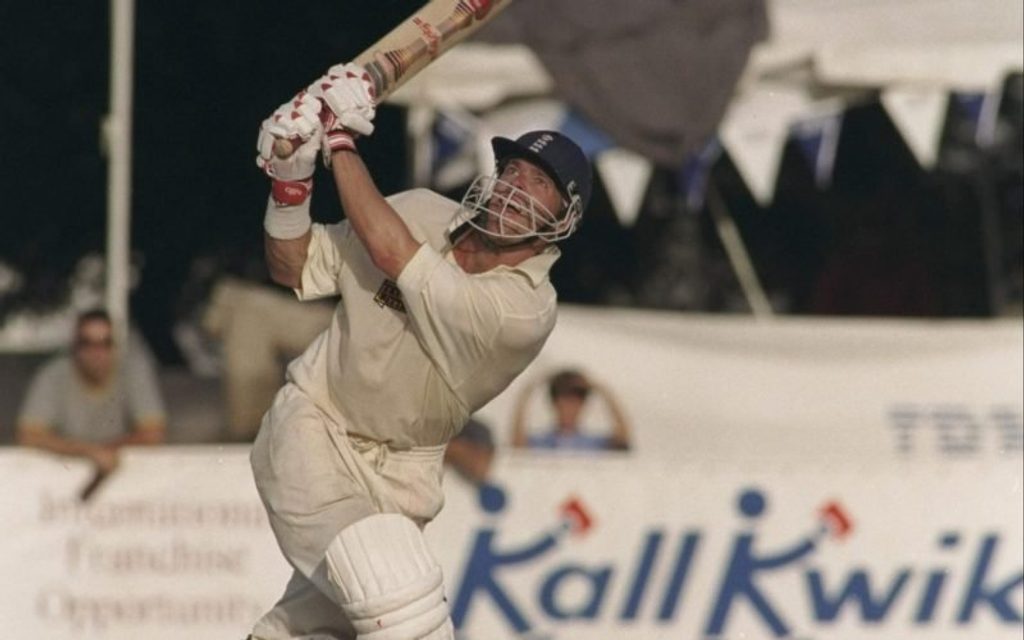

After the three-day Perth innings defeat the Aussies had retained the urn – it had taken just 11 days of cricket – and talk of a 5-0 whitewash wasn’t just idle chitchat. But at least Vaughany had continued to dazzle the crowds with his style, as well as sheer volume of runs. Sitting on the Sydney balcony, it was awesome to watch someone at the height of his game.

[caption id=”attachment_171706″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Vaughan scored a match-winning hundred in Sydney[/caption]

Vaughan scored a match-winning hundred in Sydney[/caption]

At least we finished on a high, beating them at the SCG. But my lasting memory will be bowling at Steve Waugh at Sydney. He needed four off the last ball of the day to reach his century. His home crowd resembled the one in Escape to Victory, when Stallone faced the penalty kick in the final minutes. The echo of ‘Victoire’ was replaced by the continuous chanting of ‘Steve Waugh’. Yes, he got his boundary, but it was fairytale stuff.

It ended 4-1, but maybe, just maybe, that match was the springboard for regaining the Ashes in 2005.

9. Australia 1974/75

With England in decline and without their best batsman, Geoffrey Boycott, this was never going to be an easy battle. The fact that they were facing two of the fastest and most fearsome bowlers on the planet at the time – the sweat-banded speed fiend Dennis Lillee and the less established but even quicker blond bombshell Jeff Thomson – meant that England’s mettle would be tested to the limit.

Boycott had cited the weakness of captain Mike Denness as his reason for not going. Other alleged that he was dodging the bullets. Only Geoffrey knows the real reasons.

Thomson took nine in Brisbane as England went down by 166 runs, but worse was to come. One of the few bright lights of the series was the incumbent captain, Tony Greig, who made a hundred in his sandshoes. Thommo claimed seven more in the second Test, targetting and then splicing Greig’s footwear with awful glee, as England, and their players, went down again. With spirits crushed and bones broken, in perhaps one of the most extraordinary developments in the history of the Ashes, they called up Colin Cowdrey (age: 42; condition: shapely) to provide some old-fashioned Englishness. When walking to the crease, M.C.C introduced himself to Thommo the wild man with the following line: “I don’t believe we’ve met. My name’s Cowdrey.” A rare touch of class from an Englishman in this series. His performance was no worse than many of the others.

Australia took four out of the first five, England grabbed a consolation in the sixth Test at the MCG.

8. Zimbabwe, 1996/97

A shambolic set of results, losing the one-day series 3-0, and two draws in the Test matches, but the first scrap in Bulawayo provides the lasting story.

Zimbabwe made 376 batting first, England replied with 406 with centuries from Hussain and Crawley. Bowling Zimbabwe out for 234, they had to chase 205 to win against a flaccid attack. With time the only impediment to an England win, Zimbabwe employed some dubious but frankly standard defensive tactics – legside wides, time-lasting tactics etc – which England got most upset about.

But the batters chipped away, and with 13 needed from the last over, Nicholas Verity Knight, new chinos-sporting star of Sky Sports, hit a six off Heath Streak, and got England down to needing three from the last ball. But Gough and Knight couldn’t make it back for the third and the game ended in an extraordinary draw, the only in history to finish drawn (not tied), with the scores level.

[caption id=”attachment_171709″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Knight struck a six in the final over but eventually failed to get England over the line[/caption]

Knight struck a six in the final over but eventually failed to get England over the line[/caption]

The reaction at the end was unforgettable. When David Lloyd, England’s coach at the time, uttered the line “We flippin’ murdered them and they know it!” the line had the strange effect of souring relations between the teams. It wasn’t Bumble’s finest moment, nor England’s. But worse was to come as they were bowled out for 156 in a rain ruined second Test in Harare, and then came the ODI whitewash.

Cricket writer Scyld Berry described the series as “some of the worst international cricket ever seen”.

7. India, 1992/93

Doomed from the start, Gooch’s ragbag band of troops ranged from Dad’s Army style renaissance men (Emburey/ Gatting) to some of the most statistically unsuccessful players in Test history (Blakey/Salisbury).

Gooch – problems in his private life, patently not at the races – had tried to duck out from the outset, but was eventually persuaded to captain, and the tour exemplified England’s woozy selection policy at the time, with great commitment and focused effort given to the scattergun approach. At Kolkata, the selection teddy picker picked four seamers – including workaday left-armer Paul Taylor for his debut – on a spinner’s paradise, buttressed by good old Ian Salisbury, not in the original squad but tossed in as the lone twirler after a few useful turns in the nets. A massive defeat ensued.

The farce continued at Chennai in the second. Tufnell was added as a second spinner, and Dickie Blakey, who would manage seven runs in his two-Test career, batted at number six. India racked up their highest ever total against England and won by an innings.

[caption id=”attachment_171710″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Anil Kumble bossed the England batsman throughout the series with 21 scalps at 19[/caption]

Anil Kumble bossed the England batsman throughout the series with 21 scalps at 19[/caption]

England crashed to another innings defeat in Mumbai. Graeme Hick scored a brilliant 178 to showcase his obvious potential, but Alec Stewart and Mike Atherton, the two young stars in the squad (Athers wasn’t even picked until the third match) and the obvious candidates to succeed captain Gooch, found themselves at the same end as England tried to save the match.

Anil Kumble took 21 wickets in the series – seven shy of England’s random nine-strong attack – after England’s McClarenesque manager Keith Fletcher had concluded his pre-series scouting mission with the line: “I didn’t see him turn a single ball from leg to off. I don’t believe we will have much of a problem with him.” Nice one Fletch.

6. Australia 2006/07

Troy Cooley, the Australian who coached England’s bowlers before taking up the equivalent role back in Oz, must have seen it coming. Either he’s some kind of lucky Tasmanian devil charm, or he just knew. Knew what though? Knew that it would be an incredibly tough tour, against the world’s best side hell-bent on sheer vengeance, culminating in a brave, tight loss? Or did his judgment lead him to conclude that the Test series would produce a drubbing the like of which Genghis Khan would be proud?

Talk was of the first ball, the first hour, the first session, the first day. Of setting the tone. Ricky Ponting knew this, and every moment of his first innings 196 at Brisbane was a cumulative lesson in redemption. He had held himself accountable for 2005. The resulting first-innings deficit of 445 kept the tour firmly on its slippery slope to perdition.

However in the second Test in Adelaide, this hell briefly froze over. You could almost imagine Satan himself chasing Collingwood and Pietersen, as they compiled that incredibly gutsy 310-run partnership. Unfortunately for us all, Satan manifested into a mercurial, blond leg-spinner in the second innings, serving to warm Hades once again.

Shorn of their unruffled Vaughan, their Trojan-horse Trescothick, and their reverse-swinging thoroughbred Jones, the task of winning was nigh on unachievable. Take into account the supreme physical condition and the keen mental state-of-mind of every one of Ponting’s team, and it is almost no surprise that it ended, whisper it… 5-0. Whisper it not, and you will be locked up, on the authority of the great broadcasting gods. The almighty ones have deemed it fit to oust any clip, any glimpse of Ashes 2006/07, from our screens: a complete media blackout. Did last winter even happen at all? These days you can’t be sure of anything.

5. Australia 1920/21

These were the days when an Ashes tour consigned its members to months at a time on one of HM’s most trusted vessels, and maybe the cabin fever got to them, because when they finally arrived on the other side of the world for a game of cricket, they’d lost all understanding of how to play it.

Not even the presence of the greats – Jack Hobbs, Frank Woolley, and Wilfred Rhodes – could do anything to alter the crushing outcome of the series. It may open up fresh wounds, and if so look away now, but the result was 5-0 to the Aussies.

Warwick Armstrong, who was undefeated in his ten Tests as Australia captain, passed away #OnThisDay in 1947.

The all-rounder’s @WisdenAlmanack obituary profiled an illustrious career.https://t.co/e079oOda5O

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) July 13, 2020

Much was made of how Ricky Ponting recently emulated the great Warwick Armstrong, who led the 1920/21 Aussies. Affectionately and appropriately nicknamed ‘Big Ship,’ Armstrong was a hulk of a man, and coming in to bat basically when he fancied it, he bludgeoned the tourists into submission.

You know when you’ve had a row, or lost a big game, and you sit in the car on the way home not saying a word, and the atmosphere congeals until you want to jump out the window? Given England’s noticeably inferior batting, vastly inferior bowling and the prospect of a round-the-world return journey spent licking their wounds, you can imagine the atmosphere on England’s own big ship back to Blighty. At least these days the boys get home quick, with only a 747-sized hole in the ozone layer to worry about.

4. Pakistan 1987/88

Mike Gatting’s side had just thrashed Pakistan 3-0 in the one-day series, and narrowly missed out on winning the World Cup less than a month prior. So they headed into the Test matches feeling adequately content with life…

You know the story.

To say that some of the decisions made by Shakoor Rana, and the man who perhaps gave him the Gatt-baiting idea in the first place, Shakeel Khan, were erroneous, would be to underestimate the barefaced swindling that was going on. Shakoor loved it, Shakeel loved it. Shakoor once called himself “the superpower of the game.” The attention, the notoriety, the power!

Steering clear of accusations of partiality, it was not just the English that found themselves with a rum deal. Shakeel’s tally of ‘victims’ from both sides shot into double figures during the first Test in Lahore, including Chris Broad, who made a stand, literally, when given ‘out’ caught behind. A show of inevitable dissent though it was, it only served to fan the flames.

It all exploded when, late in the second day of the second Test in Faisalabad, following some supposedly clandestine adjusting of the field by Gatting, Shakoor was overheard to mutter: “You’re a ****ing cheat”. Sweaty, tired, bemused and enraged in equal measure, Gatting had simply had enough. Much finger prodding, threats to abandon the game, political wrangling, and scribbled apologetic note-writing later, and the tour’s place in history is etched.

3. 2003 World Cup

When anything other than banal statements of support emerge from governmental spin doctors ahead of a major sporting tournament, you know trouble is brewing.

Such was the case with the World Cup campaign in South Africa and crucially, Zimbabwe, in 2003. The lead-up was unfortunately more about whether or not to travel to the Mugabe-run country, and less about winning the thing.

Results suggest that losses to India and Australia meant Nasser Hussain’s men never set foot into the Super Sixes. Realistically, the rot had set in long before. If only the performance of the powers-that-be off the pitch had matched the ballsy nature of Hussain and his men on the pitch.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

Two comfortable victories against minnows Holland and Namibia followed the forfeiture of the game in Bulawayo, for fear of being ‘sent back to Britain in wooden coffins,’ by the anti-Mugabe pressure group, ‘Sons and Daughters of Zimbabwe.’

The conditions then conspired to hand India the next game, and a morale-boosting win against the Aussies would have to suffice.

On a terrible wicket in Port Elizabeth, England mustered 204. It looked a winning score when Caddick removed the top four, only for Michael Bevan to do, well, what he always did; win the game with a perfectly paced innings. Andy Bichel was understandably man-of-the-match for his indescribable 7-20 and 34 not out from 36 balls, but without Bevan the game was England’s.

“I’m not apologising for what I said. I’m apologising for my behaviour and the way I handled it.”

A few nasty ones in this piece from the archives 👇https://t.co/FP0vzYDIuD

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) August 17, 2020

Amazingly, a place in the Super Sixes would still be theirs if Pakistan beat Zimbabwe in the last pool game in Bulawayo. Finally, there would be some justice in the whole kerfuffle.

We’ll let Nasser take up the story, from his autobiography: “It never rains in Bulawayo. Never…Yet when we turned on our TVs on the morning of the game, the start had been delayed by rain. We couldn’t believe what was happening…we were going home.” Nasser resigned a few days later.

2. West Indies 1980/81

A devastating tour, forever tainted by the untimely death from a heart attack of team manager Ken Barrington midway through the Barbados Test. Ken was one of your own, a cricket man to his bootstraps and the avuncular figure behind Ian Botham’s first foray into overseas captaincy. He lived every ball – one of life’s obsessive worriers, according to Botham – and perhaps it was this absolute immersion in the game that took him in the end.

Prior to this tragedy – needless to say a shell-shocked England were beaten heavily in Barbados, and went down 2-0 in the series – the choice of the replacement for the injured Bob Willis provoked a political outcry. Robin Jackman was born in India but raised in England and his performances for Surrey in 1980 had led to the call-up. But he had spent many winters coaching and playing in the sporting pariah nation of apartheid-rule South Africa.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

When he was picked for the Guyana Test, a local Guyanese journalist pointed out that his inclusion was a breach of the ‘Gleneagles Agreement’ (legislation against South African involvement in international sport). Once again, cricket and politics arranged themselves in an uncomfortable clinch, but with captain Botham receiving backing from the MCC, it was agreed that they would not be bullied into dropping the ‘Shoreditch Sparrow’.

There was now a poisonous atmosphere between the West Indian public and the England team, and when no agreement could be reached, the Test was abandoned for ‘visa reasons’. Jackman, who Botham says bore the whole crisis with great dignity, can now be heard delivering cricket commentary around the world, including in the West Indies.

1. West Indies 1985/86

Just prior to the 1985/86 West Indies tour, when Ian Botham came close to succeeding Roger Moore as Bond, he couldn’t have known he’d need a 007 performance to escape the tour unscathed. At the end of this particular two-month tour of duty, many of the party had been shaken on the pitch, and thoroughly stirred off it.

To the casual observer, a tour to the Caribbean is the big one. Sun, sand, sea, and… a jolly good game of cricket! Not this time. Not considering the rude health of West Indian cricket in the mid-1980s, not in the politically raw aftermath of a 1982 rebel tour to South Africa which was fronted by England’s main opening batsman, and most certainly not in the middle of the biggest tabloid witch-hunt since Charles II mentioned that he didn’t fancy those pointy-hatted old hags that much after all.

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]

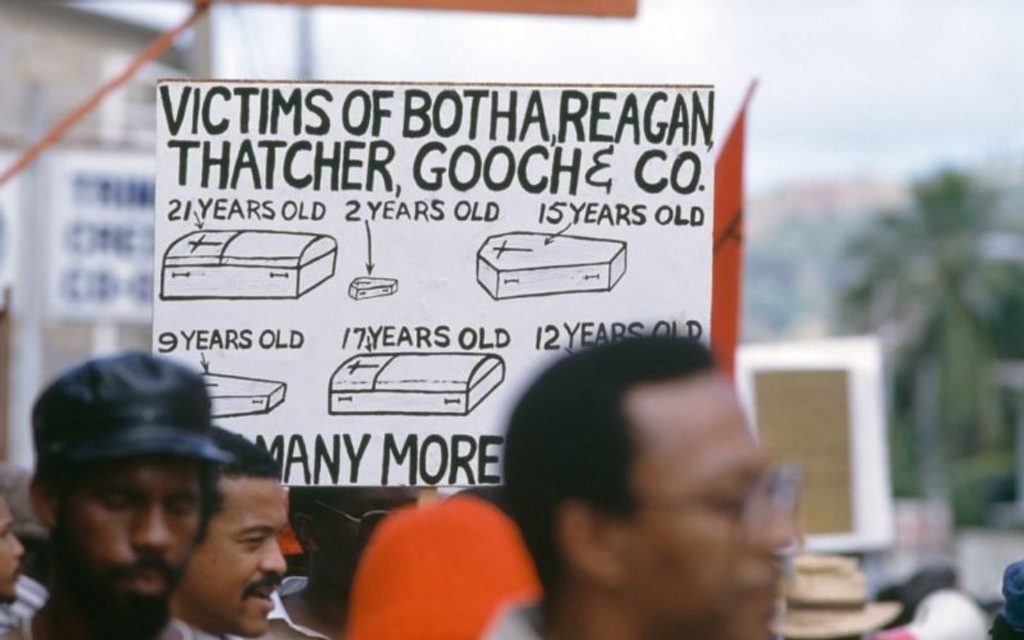

The constant threat of anti-apartheid protests, due to the status of Gooch et al as South African rebel tourists from 1982, and the statement from Lester Bird, Antiguan deputy prime minister of the time, that Gooch would not be welcome in the West Indies, hardly created an environment for a joyous tour. Coupled with the desire of the travelling press hordes to hound and hassle Botham – and anyone else for that matter – to distraction and indiscretion, and you had all the ingredients for a famously fiery trip.

On the pitch was hellish enough. First let’s consider the bowling attack that faced the recent Ashes-winning, varied and proven batting line-up of Gooch, Robinson, Gower, Gatting, Lamb and Botham. Taking the new ball were Malcolm Marshall and Joel Garner. A tough proposition, but that’s what Messrs Gooch and Robinson were there for, to stave off Maco and Big Bird.

[caption id=”attachment_171714″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Protesters display anti-apartheid slogans on banners during the second ODI at Port of Spain, Trinidad[/caption]

Protesters display anti-apartheid slogans on banners during the second ODI at Port of Spain, Trinidad[/caption]

This rarely happened of course, but with the worldly-wise middle order that England had to follow, it would surely be competitive at least, especially when the back-up bowlers were only some young kid called Patrick Patterson and a Michael Holding who’d seen better days. But Patterson was quicker than Marshall himself, and perhaps someone had riled Holding by suggesting that he was indeed past it, as these two inflicted even greater devastation. In five Tests no Englishman made it to three figures. Botham made 168 runs from ten innings.

After four thumping Test losses, a 3-1 one-day series defeat and an embarrassing loss against the Windward Islands, outright the worst side in the Caribbean, Gower’s gaggle moved on to the final Test in St. John’s Antigua, otherwise known as Viv’s backyard. The task for England was clear – avoid the ‘blackwash’ and dodge a place in cricket’s hall of shame.

Replying to 474, England battled. Gower fought harder than any, and after mustering a none-too-shabby 310 an adequate draw was within reach. Over to you Viv… With quick runs needed he strode to the crease at 100-1, and 56 balls later had mullered the fastest century in Test history, a record that still stands. The bowlers did the rest, and the series had been washed black forever.

[breakout id=”3″][/breakout]

This was the tour of bruised egos and battered balls. Twice the cherry itself found alien material lodged in its leatherness. In the first ODI at Jamaica, Mike Gatting’s nasal bone and cartilage was found, still embedded, in the shiny side when the ball was thrown back to Marshall following the scuttling lifter which rearranged Gatt’s proboscis. Botham’s autobiography recalls the Jamaican dressing room attendant ‘being kept busy for several minutes cleaning up the aftermath’ of Gatting’s attempt to blow his schnoz. And then, during Richards’ onslaught, one of his seven towering sixes flew into the stand and directly into an unsuspecting rum punch. It was not confirmed, much to Botham’s dismay, whether the glass had belonged to one of the many gutter press who’d made the trip.

And then there was the extra curricular stuff. Gower and Botham’s relaxing yacht trip when the team was succumbing to the Windward Islands didn’t look too great plastered over the red-tops of Thatcher’s Britain. Impressions weren’t helped by the constant questioning from the hacks, suppositions about who was doing what, where, and with whom. The murky mess reached its lowest point when Beefy’s alleged bed-breaking dalliance with Miss Barbados first broke. Here was a story which was unproven and flatly denied by the man himself, but by that point mud was slinging and sticking to anyone born within Britain’s borders not wearing a mac or carrying a notebook.

With Gatting’s nose splattered over his face and Botham’s name splattered over the tabs, the 1985/86 MCC tour to West Indies had its defining images.

Not one for the faint-hearted.