Rob Steen on one of cricket’s most evocative names and a key figure in the anti-apartheid movement, Basil D’Oliveira.

First published in 2007

First published in 2007

Let’s rewind to 1966. And no, not to Wembley, Sir Geoff and all the usual footie-centric stuff associated with that wondrous year. And yes, forget, for a moment, all those wars, disasters and race riots; think Blonde on Blonde, think Pet Sounds, think Revolver, think Blow-Up, think Alf Garnett, think lil’ ol’ London town when it was the creative hub of the known universe.

Between April and October, the sporting stages of our nation’s capital were graced by the three most important sporting icons of the first half of those perplexing Sixties, Muhammad Ali, Garry Sobers and Pele, lords, kings and Holy Roman Emperors of their chosen trade. Not a shabby hat-trick.

Ali made a mess of Henry Cooper’s aspirations and eyebrows at Highbury. Some scruple-free Portuguese made a mess of Pele’s knees, ensuring, with rich irony, that the star of the World Cup would instead be their own man, Eusebio, another black pearl. Sobers, captaining the West Indies, added an improbable 274 for the sixth wicket with his cousin David Holford to save the Lord’s Test. By the end of the decade, nevertheless, all three maestros would be trumped for sporting and political significance by another black man playing at HQ that day.

Sobers, a Swiss army knife in flannels and oh-so-cool upturned collar, was en route to the finest all-round Test series known to man: 722 runs, twenty wickets, ten catches. Beg to differ? Put it this way: there have been only eight instances of the 400 runs-twenty wickets double in a five-day rubber; of these, only Aubrey Faulkner (545 runs and 29 wickets for South Africa against England in 1909/10) has come within 175 runs of Sobers’s tally. Alone among the 400-20 Club, Sobers averaged 100 with bat and under thirty with ball.

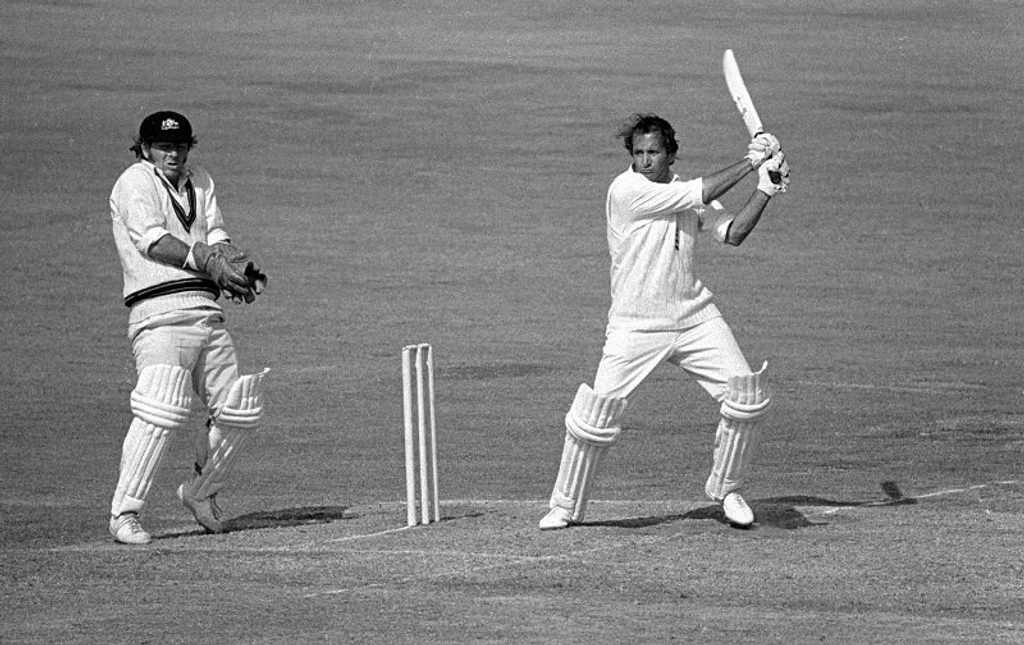

[caption id=”attachment_175686″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Basil D’Oliveira scored 19,490 first-class runs and picked up 551 wickets[/caption]

Basil D’Oliveira scored 19,490 first-class runs and picked up 551 wickets[/caption]

That second-innings stand with the ingénue Holford – which set up shop from a positively pregnable position of 95-5, nine runs ahead – was possibly the most heroic feat of the sporting summer. No sixth-wicket alliance in Tests has ever contributed as much (74 per cent) to a team’s innings.

Looking on, and comparatively unnoticed, was another all-rounder. England’s rather ancient-looking debutant, D’Oliveira of Worcestershire, had had a pretty decent start. He’d nipped out the mighty Seymour Nurse in both innings and, having been crassly dropped at the wicket off Sobers, put in some impressive short-arm drives for the Saturday full house of 30,000. After all he had endured to get this far, all the agonies and sacrifices, was it a harbinger of doom that he should be run out backing up? Jim Parks’ drilled shot rebounded off his foot for Wes Hall to complete the most unfortunate of dismissals, whereupon, astonishingly, Sobers and his men applauded him off. Can you imagine a fielding side doing that now, or ever, for a batsman who had made 27? There was relief there, sure, but that was only a small part of it. Here was black solidarity, an ingrained empathy for a fellow race warrior.

The next two Tests brought successive scores of 76, 54 and 88, six wickets and a last-wicket rally of 65 with new boy Derek Underwood, though I can’t claim, in all honesty, to have been a witness to any of this. I was eight, and the first Test I saw did not come until the final chapter at The Oval in August, by when Sobers et al had sewn up the five-match series.

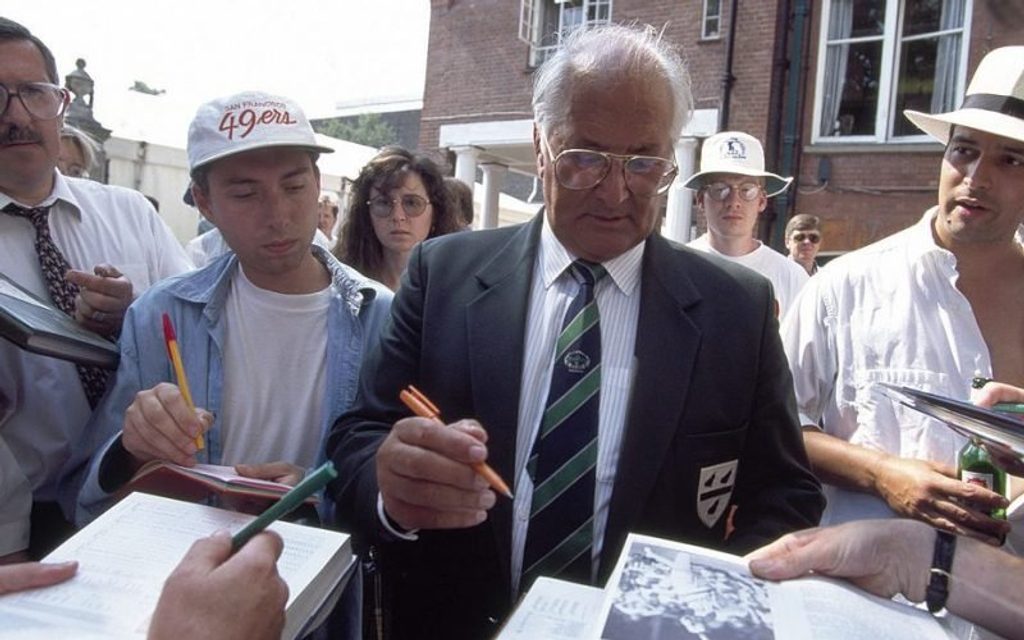

[caption id=”attachment_175687″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Basil D’Oliveira signing autographs during the Lord’s Test between England and South Africa in 1994[/caption]

Basil D’Oliveira signing autographs during the Lord’s Test between England and South Africa in 1994[/caption]

I can’t say I even noticed Dolly in that game. How could you? Tom Graveney made 165 of the most sublime runs imaginable, Rohan Kanhai was at his impish, lavish best, John Snow and Ken Higgs put on 127 for the last wicket, new skip Brian Close caught Sobers at short leg first ball, refusing to flinch an inch as the great man hooked, and England won by an innings while we were en route to Majorca.

In truth, not until the following summer (no regular winter tour back then), when he made a century in the first Test against India, did Basil dawn on my pre-teenybopper consciousness. But I was still too tender of foot to have any notion whatsoever what the expression “Cape Coloured” meant, much less apartheid. To me, he was a black South African whom England were kind enough to let play for them.

Barely a year later, though, I sat glued to the family transistor radio on a beach in Devon, cheering when Australia’s normally impeccable Barry Jarman dropped him on 31, urging him towards his century as if my life depended on it as well. By now, I fondly imagined, I was almost up to speed. By now I even knew that that fully-qualified soulless bastard John Vorster was South Africa’s PM.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

Come the fateful MCC selection meeting that omitted Dolly from the South Africa tour party, I was well pissed-off, but only as a consequence of that same boyish mentality that once enabled us to care whether The Kinks went up or down the pop charts. When Tom Cartwright pulled out (and no, he didn’t do so because he was injured but because he’d heard that the South African MPs had stood and cheered when Dolly’s exclusion was announced), joy was unconfined. The ramifications eluded me, but hey, my new favourite cricketer had been picked for his first tour…

For all the untold wonders Ali did for the pursuit of civil rights, for the eradication of racism, for the explosion of that hoary old mythical nonsense about sports and politics not mixing, Basil D’Oliveira, I would contend, was more important to the black struggle. Even Nelson Mandela has insisted that, without him, apartheid, the single most evil regime of the 20th century, would not have been conquered as soon as it was.

Unlike Ali, Dolly’s battle was a lone one, a lonely one. There was no manager for him, no cornermen, no promoter, no lawyer and no entourage of self-affirming if ingratiating hangers-on and backslappers. Nor did he have any trailblazers – such as baseball’s Jackie Robinson or basketball’s Bill Russell – from whom to draw inspiration. Nor any politician leaders – such as Martin Luther King or Malcolm X – hailing him to the skies on prime-time TV. Nor millions of dollars to cushion his rebellion.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

In resisting those Vorster-authorised bribes to pull out of the 1968/69 tour if selected, in sticking it out, sticking to his guns and sticking it to the white supremacists who gaily predicted failure when he accepted John Arlott’s invitation to leave hot, sunny and cruel Cape Town for wet, dreary and strange-but-welcoming Lancashire, what Dolly did was arguably even more sapping of will, faith and self-belief. What he did, however quietly, modestly and undemonstratively, was send a defiantly uncoded message to his people’s tormentors: these buggers can’t keep us down forever.

Basil D’Oliveira: Most Important Sportsman Who Ever Lived. Not an overly ridiculous claim.