We’re just under two weeks into the 2022 Men’s T20 World Cup, and the contrast with the tournament last year is stark.

Numerous close games, plenty of upsets, and talking points galore, this fortnight has so far been everything that you want from a global event. The match between India and Pakistan was arguably the finest we have ever seen in this format, and that magic has rubbed off on everything around it. The rain has threatened to take the edge off things at times, but as it stands, even the games that haven’t happened have added to the narrative, given the qualification scrap at hand.

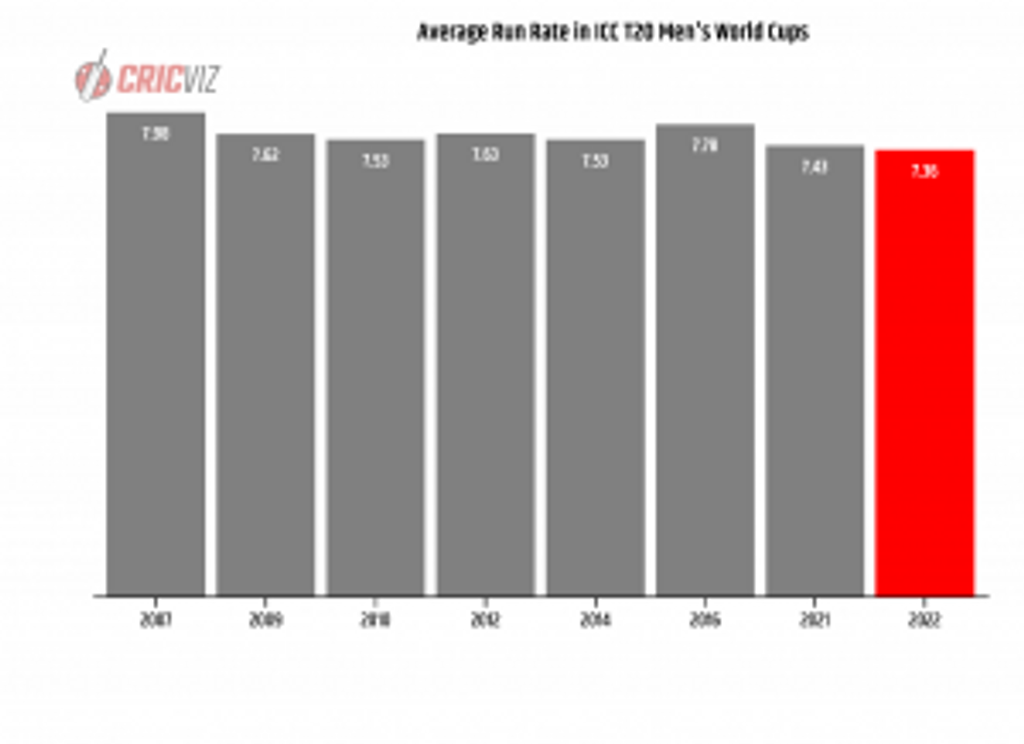

Yet despite the thrills and spills, one thing we haven’t seen are many high scoring matches. Indeed, right now the run rate for the competition is 7.36rpo, the lowest of any T20 World Cup. Generally, games have been lower scoring affairs – the scores at the MCG have been Pakistan’s 159, India’s 160, Ireland’s 157, with England not able to get up to the required scoring rate on DLS in that match.

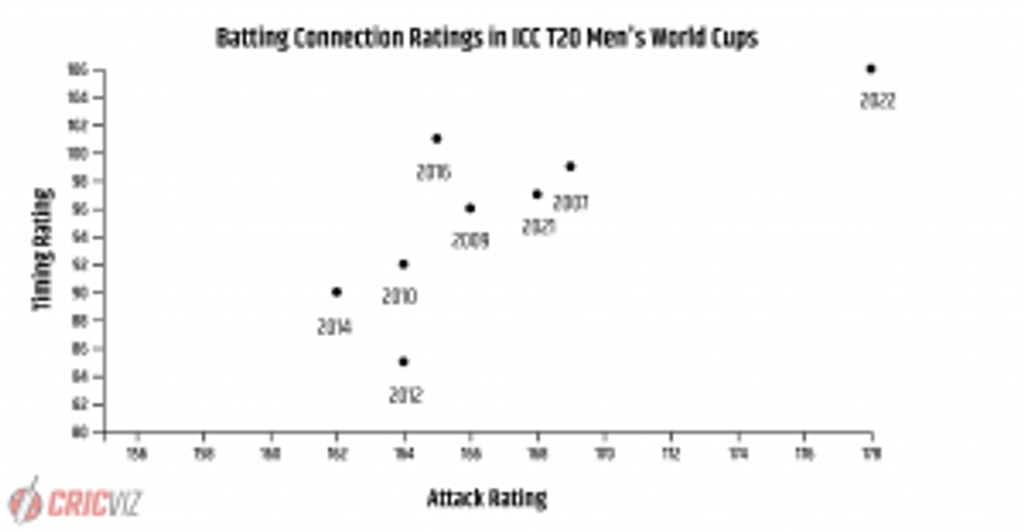

This doesn’t appear to be a result of batters lacking aggression, given that the Attack Rating and Attacking Shot Percentage, two distinct measures of attacking intent, are both the highest on record. Similarly, it’s hard to point to a lack of batting quality; the Timing Ratings we’re seeing in this competition, in essence a measure of execution, are also at an all-time high. Batters are attacking, and they’re making good contacts – but they aren’t scoring runs.

As Nathan Leamon and I explored in our book ‘Hitting Against the Spin’, the cricket played in World Cups is demonstrably different to bilateral series. You see more 90mph bowling, with teams fielding their first choice attacks more regularly and individuals pushing themselves to the limit. You see more high-intensity sprints in the field, for similar reasons, with everything on the line. Even without the ‘soft’ factors of pressure and expectation, the environments for batting in particular are generally tougher in world events.

However, on this occasion it appears that the conditions are as much to blame as the context. The key here is the unique nature of Australia as a host country, and in this particular instance, the dimensions of the venues. We’ve seen a six every 31 balls, the second highest figure for any competition. The Power Rating for this tournament – a measure of how often well-connected shots go for six – is the lowest for any World Cup. The large playing areas obviously make it harder to clear the ropes, and that’s changing the dynamic of the play significantly.

Of course, the 2021 World Cup did see conditions play a significant role. Abu Dhabi and Dubai, both large playing areas and long boundaries, were significantly different from the small boundaries and high scores of Sharjah. The dew saw chasing become a far easier route to victory across all three venues. The difference this year is that the conditions appear to be bringing sides closer together by creating a more even contest between bat and ball.

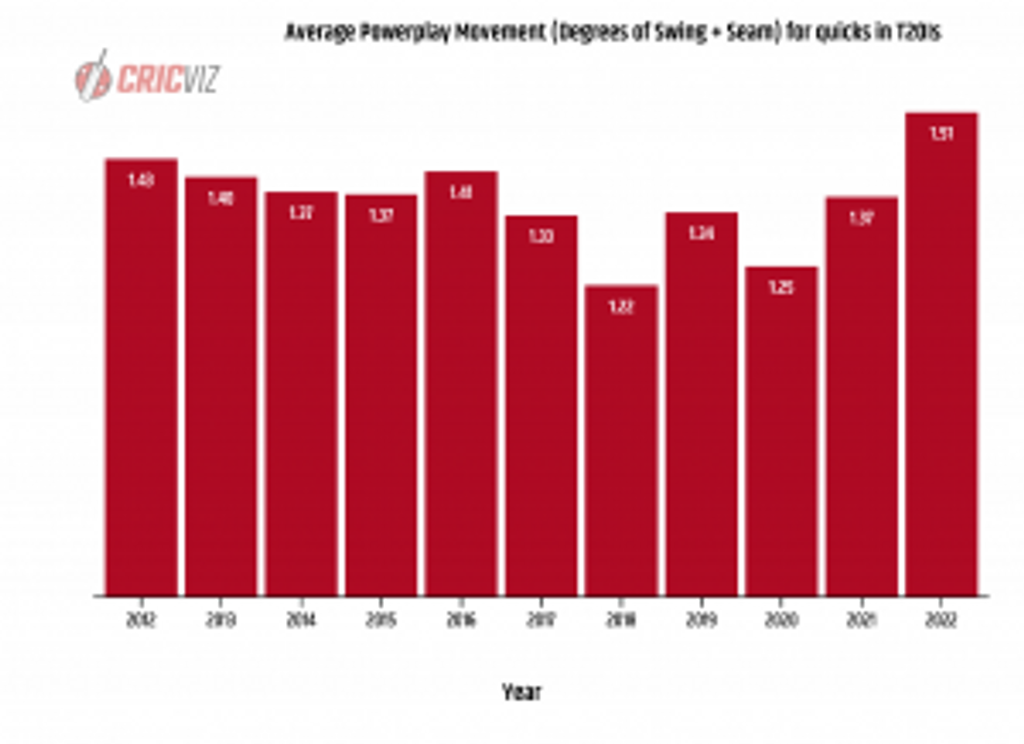

The Powerplays have been a serious test of opening batters’ ability, with more swing and seam than any World Cup since 2010. This current Kookaburra ball seems to be providing far more movement than previous versions. This year, T20I Powerplays have seen an average 0.9° of swing movement, and 0.6° of seam, both of which are the highest figures we have seen in a decade.

What’s more, it’s not only been the ball. The much vaunted pace and bounce of Australian surfaces has been clear to see. The length you have to bowl to hit the stop of the stumps as a quick bowler (6m) is the fullest for any World Cup; seamers have been finding top edges at unprecedented rates. The combination of new ball threat, bounce through the middle, then large boundaries making six-hitting at the death harder than usual, has dictated that batting against pace has never been straightforward.

What’s noticeable when you look at the main contenders for the tournament – or those that were considered such before a ball was bowled – is that only a handful of batting orders are well placed to cope with all three threats: pace, bounce, and new ball movement. Australia have been strong against pace and bounce, but average just 23 against early swing and seam in recent years. Pakistan have been excellent against the new ball of late (averaging 31), but average just 19 against high pace, and have a worse record against bounce than any Full Member barring Bangladesh. The strongest all-round batting orders against fast bowling in these conditions are India, England, South Africa, and New Zealand; they have all put up strong numbers for a sustained period of time.

With so much of the most high profile T20 cricket played in recent years coming in Asia, it’s been refreshing to see the best players pulled in a slightly different direction, and to see their skills tested in an alternative context. It adds to the richness and texture of the format – as all World Cups should.

Bet365 will be Live Streaming all of the T20 World Cup matches direct to your iPhone, iPad or Android device, as well as desktop. This means that every T20 World Cup