CricViz analyst Ben Jones dissects the recent performances of Mark Wood, the fastest bowler England have ever had.

Subscribe to the Wisden Cricket YouTube channel for post-match awards, player interviews, analysis and much more.

As England have taken a 2-1 lead over arguably their closest challengers for the T20 World Cup crown, there have been plenty of performances to cheer about. Jos Buttler’s controlled destruction of the top of the order was a joy to watch, Jason Roy has rediscovered some form, while Adil Rashid’s work in the Powerplay has somehow made one of England’s key bowlers an even more versatile and effective operator. Defeat in the second T20I has kept a lid on any overconfidence, but England have made important, if subtle, improvements throughout the side.

However, one aspect of England’s play has been anything other than subtle. For two games running in Ahmedabad, faced with some of the most impressive T20 batsmen in the world, Mark Wood has been breathing fire.

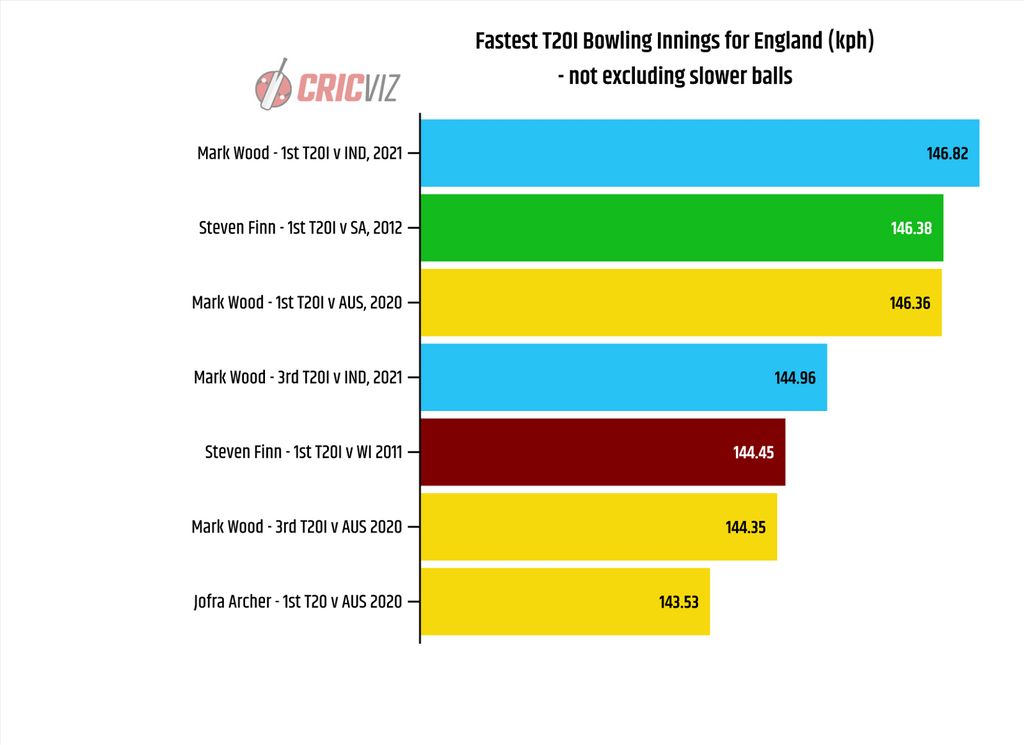

The raw numbers tell a certain amount of the story. Four wickets in 48 balls, with an economy of just 6.4rpo, is impressive work on the scorecard, but it’s been the way in which he’s taken those wickets which has caught the eye – and more bluntly, the pace at which he’s done it. Wood’s average speeds in the last two matches – 147kph and 145kph – are two of the four quickest ever T20I performances for England. Over the course of a long weekend, he’s stolen the record books and scrawled his name all over them.

[caption id=”attachment_198100″ align=”alignnone” width=”6600″] CricViz: Mark Wood has bowled four of the six fastest spells by an Englishman in a T20I[/caption]

CricViz: Mark Wood has bowled four of the six fastest spells by an Englishman in a T20I[/caption]

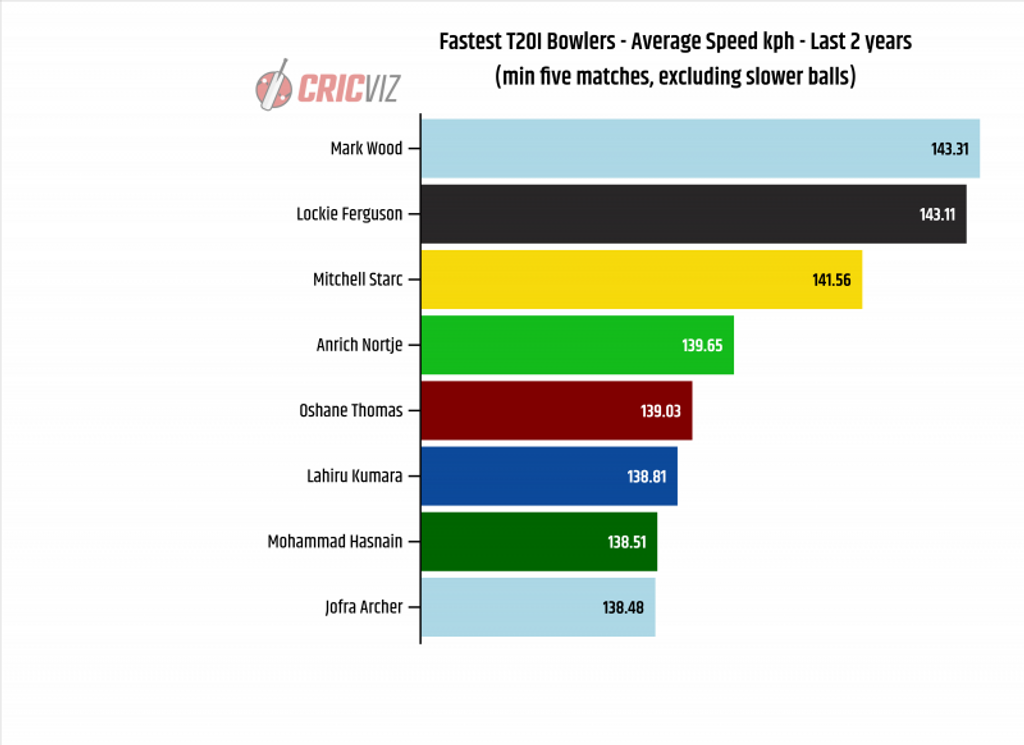

These performances aren’t a shock by now. England’s enforcer is the quickest T20I bowler in the world. There are nuances to bowling quick, the whens and wheres, but ultimately cricket can be a simple game. A 150kph bowler, hurling a rock-hard new ball at your head, then your stumps, is not pleasant. Analyse it all you want, but pace is pace.

[caption id=”attachment_198101″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] CricViz: Mark Wood has the fastest average speed of any T20I bowler in the world in recent times[/caption]

CricViz: Mark Wood has the fastest average speed of any T20I bowler in the world in recent times[/caption]

High speed bowlers are often associated with death bowling, and spearing in yorkers in the final overs. And yet for England, the benefit of Wood’s aggression has come much earlier on in the innings. Before this series, England had been finding it really tough to take Powerplay wickets, and since their 2019 series against the West Indies, they had gone two years with the worst Powerplay bowling average of any Full Member in the world. Many had criticised the premature move away from David Willey, a bowler with a T20I Powerplay record that stands comfortably alongside the best ever in the format.

However, they’ve now played three matches in this series, and taken three Powerplay wickets in two of them – largely thanks to the work of Wood, whose strike rate now compares very favourably to Willey’s. While Sam Curran has shown signs that he’s the more natural heir-apparent to Willey’s left-arm new ball swing, for now England are happy to back Wood and Archer’s ball-speed as their primary Powerplay threats.

However, Wood’s effectiveness isn’t only limited to the Powerplay. A key tactical trend of modern T20, in the leagues more than international cricket, is the deployment of two high pace quicks in the same attack, often overseas players, with at least one of them bowling through the middle overs, countering spin-strong batsmen who have been groomed for that role. Wood, alongside Archer, allows England to do this.

The dismissal of Shreyas Iyer on Tuesday was a textbook example; Iyer is an excellent player of spin, and a capable player of standard pace, but he has an issue against the short ball, particularly when delivered with a bit of venom. Previously, batsmen of his type could safely bat at No.4, avoid the new ball and the death overs, and avoid this high pace threat – but not any more. Wood was used specifically to target Iyer, and bounced him out.

Wood’s record in the last two years is the backdrop to this wicket, the proof right there that it wasn’t a fluke. He is incredibly effective for England through the middle.

[caption id=”attachment_198099″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] CricViz: Mark Wood is more effective in the Powerplay and the middle overs than he is at the death in T20Is[/caption]

CricViz: Mark Wood is more effective in the Powerplay and the middle overs than he is at the death in T20Is[/caption]

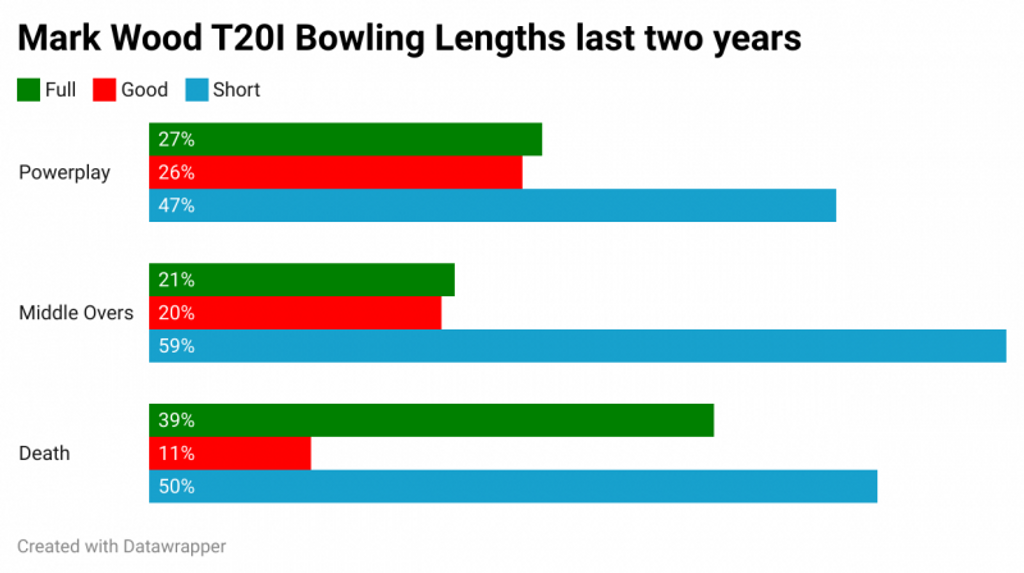

One thing England will want to keep an eye on, is Wood’s performance at the death. During this latest version of Wood, England have rarely used him in the final overs, and when he has it’s not gone well. Only 36 of his 198 T20I deliveries in the last two years have been at the death, but they’ve gone at 10.7rpo, with an Average Bowling Impact of -0.7. In part, it may be an understandable attempt to vary what’s worked throughout the match; his lengths in the first two phases of the games err strongly towards shorter lengths, but at the death he goes much fuller, and all but abandons good length deliveries.

[caption id=”attachment_198098″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] CricViz: Mark Wood bowls much fuller at the death than he does at other phases of a T20I innings[/caption]

CricViz: Mark Wood bowls much fuller at the death than he does at other phases of a T20I innings[/caption]

England are keen to adapt their plans to the opposition and surfaces with which they are confronted – their determination to bowl nothing but short balls to Hardik Pandya shows this quite clearly – but Wood may need a more consistent method in order to perform at his best. The use of an effective slower ball, something which has been a very small feature of his death bowling, might make him a touch more effective in this later phase. England’s sparing use of Wood in the final stages of the innings insists that it’s not a big issue in isolation, but just one worth following.

Wood’s had an odd career, in some ways. He’s won an Ashes series, and taken the wicket to secure it; he’s won a World Cup, as a crucial cog in England’s attack; he’s developed a public persona which has resonated with England fans, and made him one of the most universally loved members of the national side.

https://twitter.com/ibuprofenfan/status/1371909040922624000

He has already achieved more than the vast majority of professional cricketers could dream of. And yet, this year will be the one which decides Wood’s legacy.

His exploits in South Africa and the Carribean across the last two winters are the stuff of legend, but for English fans Australia is still the dream. His white ball strength is no purple patch, and he can look forward to the lucrative offerings of domestic T20 leagues very shortly, but leading England to a second white ball title in two years would cement him as one of England’s finest bowlers. It is hard to overstate Wood’s importance to winning the Ashes, and the World Cup, but also the importance those matches will have in shaping the reputation Wood leaves behind once he’s gone.

This return to the side followed a match off, after he’d pulled up sore following his four overs on Friday night. Before that, well-documented injuries and rehab have limited Wood’s time on the field. It’s to be expected – with reasonable certainty, we can say Wood is the fastest bowler England have ever produced. There haven’t been many, ever, who have bowled quicker than Wood for any period of time. The strain on his body is obscene, because what he’s producing is almost unprecedented.

An issue with the rotation policy which has dominated conversation of late, is that it’s hard to get behind a plan which, by its very nature, takes cricketers away from view. Deep down, no England fan can find it easy to support a policy which deprives them of watching Jos Buttler, Mark Wood, Jofra Archer. But the ECB and the staff involved in making these decisions need to borrow some Don Draper wisdom – if you don’t like what’s being said about you, change the conversation. Because the flipside is that what the rotation policy does allow you to see, is Wood in full-flight, fully fit and raring to go. All being well, it should allow you to see that in a World Cup, and an Ashes series.

Because until those matches, Wood should be doing…not a lot at all. Some matches in the The Hundred to keep the machine running smoothly, select games for Durham, the odd ODI appearance as England rotate through their catalogue of seamers, but the temptation to pick him in the Test side – in home conditions – should be ignored. England are well stacked for swing and seam options, and the emergence of Olly Stone gives them the opportunity for some 90mph muscle without compromising Wood’s fitness. The risk associated with Wood playing Test cricket before the Ashes, and breaking down, is simply too great – because the reward of England getting him at his best, for a career-defining six months, is perhaps even greater.