CricViz analyst Ben Jones looks at the impressive performance of Chris Jordan in England’s T20I series defeat to India.

In the conversations surrounding Eoin Morgan’s departure as England white ball captain, there was never a debate over who would be the next man to take up the job. Jos Buttler has been groomed as Morgan’s successor almost from the day he took charge, and the wicketkeeper’s excellent form with the bat – plus his demotion from the Test side – only made the case clearer. There were occasional muted calls for Moeen Ali as an outsider pick, but in general, people were sold on Buttler.

One name which seemed to be absent from the discussions was that of Chris Jordan. In some respects, this was a surprise; Jordan is immensely experienced both for his country and in T20 leagues around the world, is England’s leading wicket taker in T20 internationals, and has leadership experience in domestic cricket. Add to that his status as a universally popular and well liked member of the dressing room, and here stood a great candidate to take the armband.

And yet in other respects, his absence from succession talks was not a surprise at all. In recent times, Jordan’s stock has fallen significantly. Despite having a solid T20 World Cup overall, his mauling at the hands of Jimmy Neesham in the semi-final last year was the defining moment of England’s campaign, as they let slip a strong position and failed to reach a third final under Morgan’s leadership. Six months later, Jordan followed up with a very difficult tour of the Caribbean; across four matches, he managed just one wicket, conceding 136 runs and going at more than 10 runs per over. Shortly after came a poor performance in the IPL for Chennai Super Kings. Jordan’s trajectory was not good, and his place in the England side was far from secure.

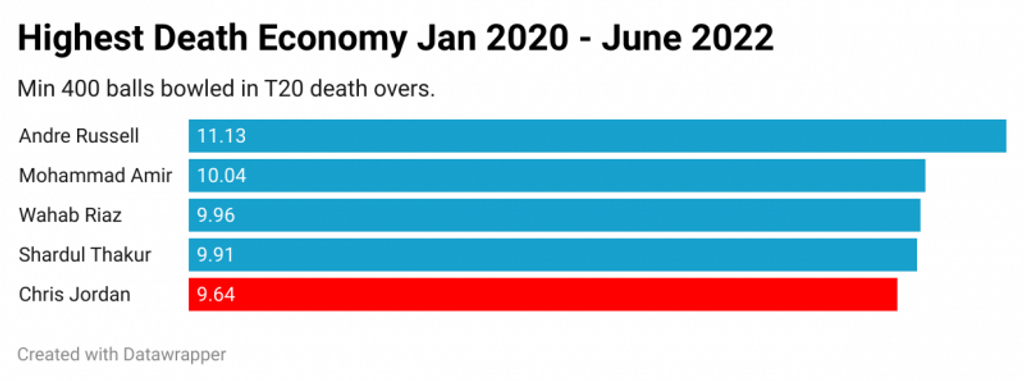

Increasingly, his reputation as one of the world’s best T20 bowlers – death bowlers, specifically – has been a result of his own commitment to the format, rather than excelling within it. The role of death bowler is always a volatile one, but in recent years Jordan’s standards have often fallen well below the elite. There was a sense – as written on this site – that Jordan’s trademark yorker hunting method was becoming too predictable against the best in the world.

[caption id=”attachment_259472″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] CricViz: Chris Jordan’s economy rate in the death overs is the fifth-worst in the world in recent times[/caption]

CricViz: Chris Jordan’s economy rate in the death overs is the fifth-worst in the world in recent times[/caption]

Yet this summer has offered something of a rebirth. The T20 Blast has offered a welcome return to form, as Jordan captained an outstanding Surrey side to the quarter-finals of the competition, delivering strongly on a personal level taking 17 wickets in 13 games.

More impressively, that form followed through into an excellent showing against India this last week, with five wickets and an economy a tick under seven runs per over. His Average Bowling Impact, +6.3, is the third best he’s ever managed in a series for England, a substantial turnaround in a very short space of time.

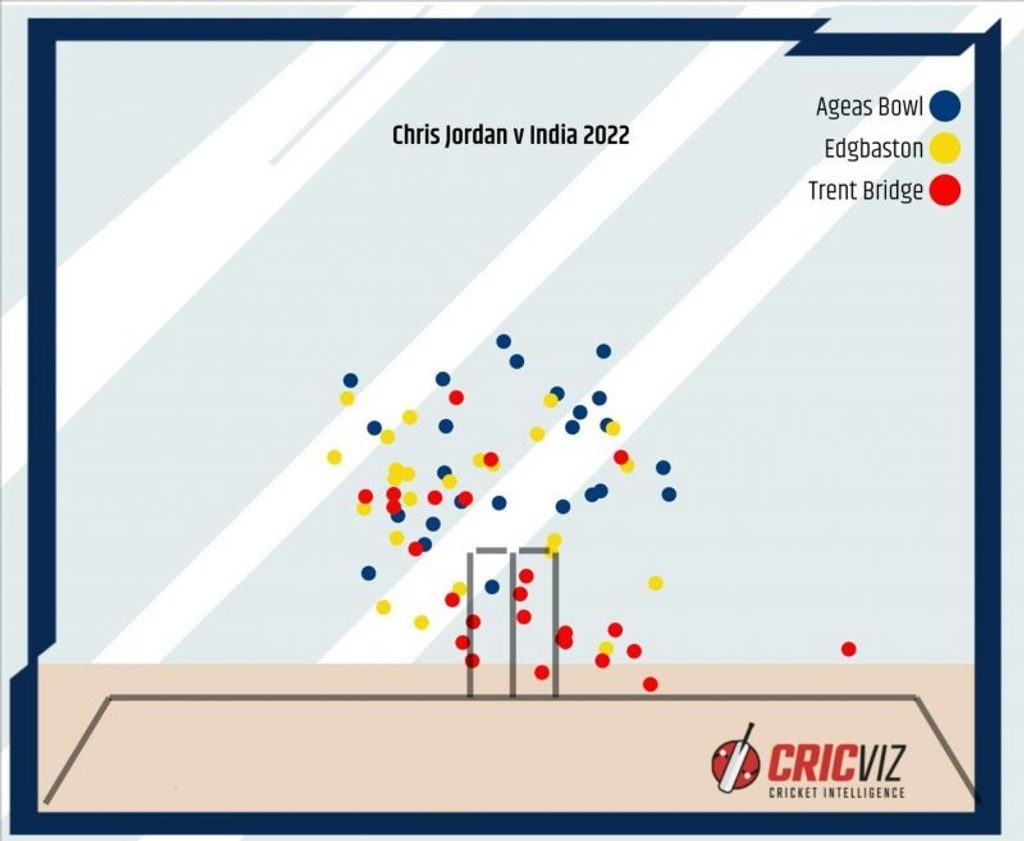

This renaissance has coincided with a clear strategic change in Jordan’s bowling. More than half of his deliveries against India were classified as ‘short’, the first time that’s ever been the case in a bilateral series; in the opening match at the Ageas Bowl, only two of his deliveries were pitched full of a good length. More so than ever before, Jordan was moving away from his classic yorker strategy, and towards a method of hitting back of length, or ‘hard length’, as often as possible.

Statistically, a landed yorker is an outstanding delivery, but the average bowler lands one out of three. Even the best in the world only nail around one in two, and Jordan is not at that level. And while a successful yorker will earn you a dot, a failed yorker is pretty much the most expensive ball in the game; on average, you’re giving up two boundaries to get that dot ball – it’s not a good exchange rate. In T20 cricket right now, an attempted hard length delivery is on average a more consistent, reliable death overs option than an attempted yorker.

Of course, a degree of Jordan’s change in approach will be because of the batters involved. Hardik Pandya is a highly skilled hitter who destroys anything pitched up, but struggles against quicker, shorter bowling. There’s also an element of the conditions encouraging a certain approach, with England often adopting a back-of-length strategy when they play in Southampton, using the large boundaries at the Ageas to their advantage; at Trent Bridge, faced with a set Suryakumar Yadav on a very flat track, Jordan returned to his yorkers.

[caption id=”attachment_259473″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] CricViz: Chris Jordan’s deliveries by venue[/caption]

CricViz: Chris Jordan’s deliveries by venue[/caption]

It helps that he’s bowling with heat. In Nottingham, 20 of Jordan’s 24 balls were above 140kph, a figure he’s beaten only once in a T20I for England. That pace was there all series, and the combination of that pace and his change in length has been hugely effective. What’s more, Jordan’s success wasn’t only about length, but also line. More often than not, he was able to bowl that length and still get in that channel outside off, with 56 per cent of his short balls this series coming on that line – he’s never managed a higher figure in a series. It also points to why Jordan was less successful with this approach in the World Cup, given that he was hitting the channel with only 30 per cent of his short balls during that tournament. When bowling to the world’s best, these margins matter.

Death bowling, or any bowling in fact, is about striking a balance between delivering your best ball as often as possible, and having enough variation to keep the batter second-guessing. The challenge for Jordan is to blend his new approach with his old one, to carry through the strengths associated with finding that blockhole and smashing out yorkers, but combine them with the strengths of high pace into the ribs.