Back in 2009, Ben Dobson wrote about Malcolm Marshall, a smiling Bajan revered as one of the world’s greatest-ever fast bowlers.

Published in 2009

Published in 2009

To be the most lethally effective fast bowler of your generation and somehow remain universally liked, even loved, by peers and fans alike, is a special achievement. But ‘Maco’ was pretty special.

When cancer took him tragically early at the age of 41, former team-mate Colin Croft said that it was as if one of his relatives had died. He doubted there was anyone in the world, player or spectator, who had been touched by Maco, who would not have something good to say about him. He was right. And given that Maco had spent a career splintering stumps, and in the case of Mike Gatting, a nose, this points to a singular character. At a time when the game was becoming more commercial, intense and confrontational, he lost none of his fierce pride and competitiveness and still managed to play and live with a smile on his face.

If you grew up, as I did, as an English cricket lover in the Eighties, you will recognise the struggle I had in trying to enjoy the exploits of some undoubted greats of the game who were regularly engaged in dealing out thrashings to England. Once they had retired and they could inflict no further damage, of course, I was big enough to miss them. But at the time, there was this terrible dichotomy; they were lighting up the game but ruining my summers.

For a young Hampshire and England fan, one of the benefits of South Africa’s absence from the international game was being able to enjoy Barry Richards safe in the knowledge he could cause me no real pain. When I saw Shane or Viv or a Carl Hooper cameo, I knew I was watching greatness and should enjoy it rather than just appreciate it. I tried and, regularly and shamefully, failed; but that is my problem, my loss, not theirs.

Malcolm Marshall was somehow different. There was a certain ghoulish fascination, sadistic and masochistic in equal measure, in watching him dismantle my favourite batting line-ups, not to mention Gatt’s nose. How could a man inflict such physical and mental torture on my England heroes and still become my favourite cricketer? Lest we forget, he was a phenomenal player – perhaps the most complete fast bowler of them all, with figures to match. A Test average of 20.94 and strike rate of 46.76 are tartling enough. An ability to switch from venomous pace to artful swing and cut, based on the prevailing conditions, made him extra special.

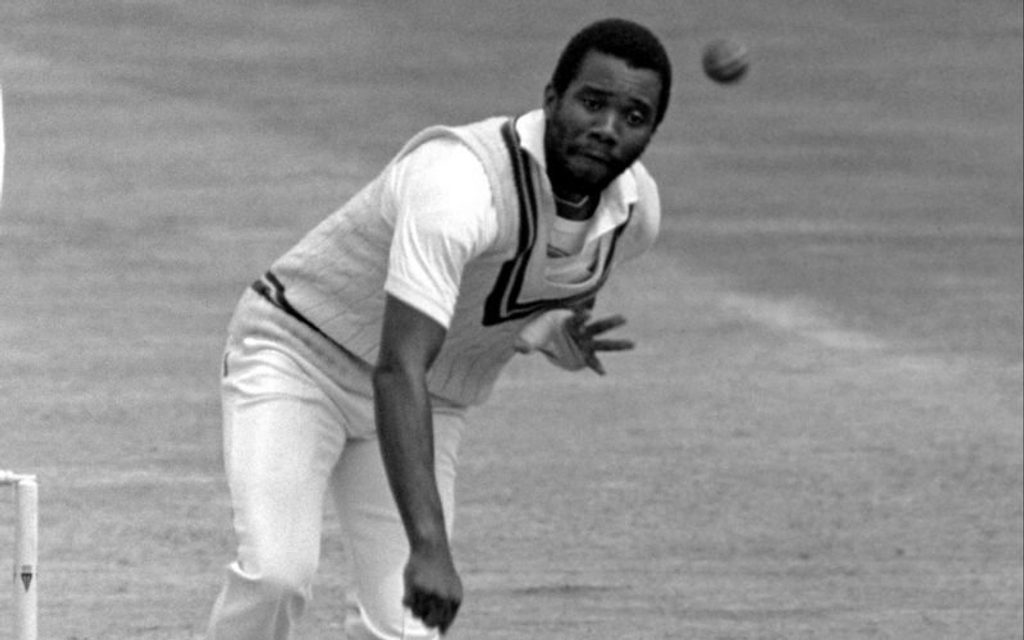

The most iconic image is probably his (literally) single-handed destruction of England at Headingley in 1984, taking 7-53 with one arm in plaster. Personally the more lasting memory is of being there to witness an even more mesmerising 7-22 taken on a slow Old Trafford pitch four years later, using leg cutters and pitched up swing – he was no one trick pony. The short stepped, curving run, the whoop of delight, the arm raised in triumph and the flashing smile will remain a fond memory as long as I follow the game.

Malcolm Marshall bowling with a fractured left hand at Headingley

Malcolm Marshall bowling with a fractured left hand at Headingley

They say you should not get to meet your heroes as they are likely to disappoint you. Maco never did. The root of the affection I have for Maco lies as much with the man as with the cricketer. In these bewildering days of the instant overseas player, hired for a month or so and seemingly gone before they have arrived, it is easy to forget a time when players from all over the world could become so interwoven into the fabric of a county that they stayed forever, in spirit if not in body. So it was with Marshall and Hampshire. He became not only one of the greatest servants the county ever saw, but also a true son of Hampshire. His love for the place and the pleasure he gave were epitomised by his unrefined joy in winning the Benson & Hedges Cup in 1992, having missed the long awaited one-day triumphs of 1988 and 1991 whilst touring with the West Indies. The road at the Rose Bowl which now bears his name, along with that of his fellow Bajan and namesake, Roy, is merely a physical confirmation that, for us, he will always be around.

Walsh: 519 wickets at 24

Ambrose: 405 wickets at 21

Marshall: 376 wickets at 21

Garner: 259 wickets at 21

Holding: 249 wickets at 24

Roberts: 202 wickets at 26

Croft: 125 wickets at 23Which of these great West Indian fast bowlers was the greatest, in your opinion? pic.twitter.com/n1EF4chhYF

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) November 25, 2020

Later in his career I was lucky enough to get to know the man when the cricket company I worked for began to supply him with equipment. A meeting with Maco was always fun, and I was unfailingly greeted with a glowing smile, regardless of how many overs he had put in that day and how mine was probably the last face he wanted to see at the time. A meeting arranged at the 1991 NatWest final, partly to supply a bat for the ’92 World Cup, rather fell apart when Hampshire’s first victory in the competition saw your correspondent, somewhat the worse for wear, running around the Lord’s outfield waving said bat around his head. It was later used for an impromptu game of cricket with an orange on St Pancras station, and never made it to South Africa. It was not my finest hour professionally and many sports stars I have come across would, quite understandably, have been rather upset. Maco thought it was priceless.

That he made a mark on those who met him was brought home to me by the emotional involvement I felt when he died in 1999, the level of which caught me by surprise. Ours was a fleeting acquaintance rather than a friendship but that smile was something I shall never forget.