From Curtly Ambrose’s Perth brilliance to England’s not so amazing Adelaide, Phil Walker and Will Smith on the tales of Test cricket’s most epic batting collapses.

First published in 2008

First published in 2008

In cricket’s vast library of agonising moments, the doomsday book of infamous batting collapses sits at the top of the pile. For the bowling side, unexpected joy. But for those rooting for the batting side, watching their boys fall like ninepins to lose at the death is the worst feeling in the game. Just ask those Englishmen who happened to be in Adelaide two Decembers ago. Here’s a look at that and the rest.

10. Sri Lanka v Australia, Colombo, 1992

Long before poker was even a twinkle in his eye, back when Shane Warne would dream of XXXX and playing footy for St. Kilda, and on the back of nascent Test figures of one wicket for 335 runs, came the first hint of what was to come.

In tandem with Greg Matthews, and defying a first-innings deficit of 291, Warne bowled Australia to a ridiculously audacious win. The Aussies had ground out a second innings of 471, serving to at least make it interesting, but all reasonable thoughts were on a famous Sri Lankan win. Aravinda de Silva had stroked a nonchalant 37 before Allan Border took a brilliant tumbling catch to dismiss him, running fully 30 yards in the process. That was 127-3, which would become 164 all out, leaving the distraught Lankans 17 runs shy of the target.

Warne took the last three wickets, and critically was trusted with the ball at a vital time in the game – a move that proved to be yet another Border masterstroke. In Warne’s words: “I felt like I belonged.” The story had begun.

– WS

9. Sussex v Surrey, Eastbourne, 1972

Eastbourne is famed for its grand Victorian hotels and septuagenarian visitors. What transpired in the final few overs of this County Championship game however, would have had the old codgers choking on their afternoon scones. Pat ‘Percy’ Pocock was a fine off-spinner, in a golden era for English tweakers, and he was an even finer chap. Many can recount Percy’s many japes, tales and yarns – and August 15 1972 always features prominently.

Having been set 205 to win, after three rain-forced declarations, Sussex were cruising at 187-1 with three overs remaining. Percy’s figures at that stage were an uninspiring 14-1-63-0. Cue mayhem. At the beginning of the third last over, the Surrey coach Arthur McIntyre had phoned the dressing room to hear of the impending defeat. Roughly 20 minutes later he hung up, sure he had been the victim of an elaborate practical joke. Percy’s last two overs brought three world records, all of which are likely never to be threatened.

Here goes…the score with three overs left: 187-1. The final score: 202-9 – a somewhat anticlimactic draw given the circumstances. That the middle over, bowled by Robin Jackman, was taken for 11 runs, is just incredible. It means Percy’s dozen wicket-infested balls included a hat-trick, four in four, five in six, six in nine, seven in 11. Oh, and there was a run-out off the last ball of the game. Sussex had lost eight wickets for 15 runs in 20 crazy minutes and 18 absurd deliveries. By the end of it Percy’s figures read 16-1-67-7.

To quote the final statement relayed to McIntyre on the phone, taken from Percy’s memoirs: ‘Coach, you’re never going to believe this!’ Quite.

– WS

8. India v Australia, Sydney, 2008

Racism, spirit of the game, bad umpiring, claimed (non-) catches, blah blah blah. It seems this Test match has been dissected from every possible angle. Except, it seems, from the ‘it was a bloody cracking game’ angle, and that India’s hurried demise, from their assured Kumble-Dhoni entrenchment, was simply stunning.

Stunning for two reasons. Firstly, India lost three wickets in five balls in the penultimate over of a game they didn’t deserve to lose. And secondly, the protagonist was the altogether non-penetrative Michael Clarke and his round-arm darts. Though when you consider Clarke’s second ever Test spell had brought him 6-9 against India in Mumbai in 2004 – to date the only other time he had taken more than one in an innings – then you may question Ponting’s disinclination to throw him the ball earlier.

“Seldom can one Test have been so simultaneously thrilling and disturbing.”

From the archives, looking back at the infamous Sydney Test between India and Australia, and its gripping final session.https://t.co/J8uemdPG0E

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) August 2, 2020

It’s the first ball of the 71st and penultimate over. He catches the edge of Harbhajan’s bat, and Hussey takes a simple catch. Second ball he traps RP Singh dead in front. So out strides Ishant Sharma, bizarrely with two right-handed gloves – deliberate stalling tactic, or action of a monumentally nervous young man? He survives two balls and India have hope. Kumble has a word in his ear. Two more blocks and Kumble (who was blocking his life away at the other end) would surely have thwarted whoever Ponting unleashed for the last over. Two balls. A nervy waft and it was all over, Hussey again the snarer. Sadly it is a Test that will be remembered more for its malevolence than its breathtaking conclusion.

– WS

7. England v Pakistan, Old Trafford, 2001

Any Test that lasts deep into the final session of the final day is generally a bore draw or an absolute cracker. Old Trafford – that most famous and traditional of venues – has seen fair share of both. If the grand old pavilion could talk it would recount tales of Laker ten-wicket hauls, Warne wonder balls and West Indian barbarity. There would be one other tale that may sneak in too – the one of the day that eight wickets fell in the final session, and Old Trafford turned into Karachi.

On a pitch that Waqar Younis described as ‘the best we have played on,’ the game snaked towards a tumultuous conclusion. Centuries from Inzamam-ul-Haq, Michael Vaughan and Graham Thorpe, plus an imperious second-innings 85 from Inzy, laid the foundation for a last innings England run-chase of 370. A tough, tough task, but one that was drawing ever closer. Until fifteen minutes before lunch that is, when the promising opening stand between Michael Atherton and Marcus Trescothick was ended by a Waqar yorker. 146 for 1, and the shop was shut. England now wanted the draw, and with it a satisfying series win.

Given England’s documented middle order frailties, this was a risky option. One which seemed even less wise given that Waqar and Wasim were the two best exponents of old-ball bowling around, given also that they were great new ball bowlers, and given that Saqlain, on a dry fifth day wicket, is no walk in the park. You could claim hindsight is a wonderful thing.

That England were 201/2 soon after tea, when the new ball was taken, should have given them enough to stave off defeat and navigate a safe path. History charts a different course, one that led to a rousing Pakistan victory. All through some extraordinary bowling, batting lacking in clear judgement (Alec Stewart allowing a dead straight Saqlain delivery to thud into his front pad), some shocking umpiring (no Shep!) and a candidate for catch of the series to seal the deal (Imran Nazir’s one-hander to dismiss Darren Gough).

Waqar Younis sends Graham Thorpe’s off stump cartwheeling

Waqar Younis sends Graham Thorpe’s off stump cartwheeling

England had lost their last seven wickets for 48, on what was still a good wicket. A result that was a fitting tribute to the skill and perseverance of Wasim, Waqar and Saqlain. And also to Manchester’s Pakistani population, who had vacated curry mile, descended on Old Trafford in their droves, and become part of the ground’s hallowed history.

– WS

6. England v Australia, Edgbaston 1981

A fortnight after the Headingley miracle, all the brilliance of Bob and Beefy looks to be coming undone. On Edgbaston’s crackling minefield of a pitch, baked solid under an untypically vicious English sun and as dry as the parched outfield, Australia are 105-4 in pursuit of 151, and a 2-1 lead in the series. At Leeds they’d been dispatched for 111 chasing 130, but this was the side of Border, Marsh, Lillee and Yallop, all seasoned gunslingers. Surely it couldn’t happen again.

Australia need 46 to win with six wickets in hand and Border, their best player, at the crease. Mike Brearley moseys over to Botham to prod him for one last spell. Beefy, in his wisdom, suggests that maybe Pete Willey, a part-time off-spinner who gives it a rip, should be given a few overs. Botham recalls in his autobiography a further conversation between Brearley and umpire Dickie Bird. “I think it’s all over, skipper. Best thing you can do is put on the twirlers so we can get off early,” offers Dickie.

The next over changes the game and the series. Suddenly John Emburey gets one to spit at Border, who fends it to short leg. Five down. The door is ajar. Willey is forgotten. Brearley throws Botham the ball. The crowd is frazzled by heat and hope, but as the bulwark jounces in, off an arced run and with that irrepressible leap in delivery unmasking brown sweat stains under his armpits, the hordes scream themselves dry.

Round the wicket Botham pitches one straight and true and Rod Marsh tries to hit it over the gantry. He misses. Middle pole unearthed, 114-6. In comes Ray Bright, a canny and prodigiously bearded bowling all-rounder who made runs at Headingley. A beard for a crisis. Botham screams a yorker under his bat first ball.

The next to go is Dennis Lillee, slashing at a wide half volley, where Bob Taylor juggles it before pouching the bounce-out. Then the big one. Martin Kent, a stylish number five, is the last remaining batsman. Eight down with 30 still needed, Botham spears another into leg stump and Kent’s whip shot misses the missile. When last man Alderman is bowled, just like the rest, Botham has taken five wickets for one run in 28 balls, and Australia has lost six wickets for 16 runs. In his follow-through he grabs a stump, spits, and sprints through the throng towards the pulsing dressing room. Another miracle accomplished. Next!

Botham later wrote: “I had bowled well – fast and straight – but on that wicket it should not have been enough to make the Aussies crumble that way. The only explanation I could find was that they had bottled it.” You can well imagine the smile drifting over the old boy’s face as he put those words to paper.

– PW

5. New Zealand v Pakistan, Wellington, 2003

During the early years of this century, the Kiwis couldn’t work out whether they wanted to flay the Pakistani attack everywhere or collapse in spectacular style. They did both in equal measure. In March, 2001 they managed to lose nine wickets for 26 runs in Auckland at the hands of Mohammed Sami. Yet worse was to come.

The 2002/03 series lurched from one extreme to the other for the Black Caps. The first Test in Hamilton saw them plunder 563 in the first innings, followed by a twitchy 96-8, after Moin Khan had nurdled Pakistan out of a thumping loss. The second Test followed a similar pattern. New Zealand rack up 366, thanks to a turgid seven-hour 82 from everyone’s favourite stonewaller, Mark Richardson. In reply, Pakistan scrap to 196, surrendering a seemingly insurmountable lead of 170. New Zealand then close the third day on 75-3 – an overall lead of 245.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-ckTHnU9VA

The fourth day dawns, and again Richardson is sticking like mud slung at a bent politician. They reach 95-3 when he wafts at a wide one from Shoaib Akhtar. 51 minutes later New Zealand are 103 all out – having lost seven wickets for eight runs. Scott Styris is bowled off an inside edge first ball, Daryl Tuffey is run out comically by Craig McMillan, Shabbir Ahmed traps left-handers Jacob Oram and Daniel Vettori lbw, and finally Shoaib’s violent reverse-swinging boomerangs account for tail-enders Robbie Hart and Ian Butler. Collapse complete.

Pakistan are thus set a difficult 274 for victory, which they accomplish with inevitable ease, three down. The Kiwis had not just snatched defeat from the jaws of victory, they had reached down its throat, bowel deep and somehow dragged it out.

– WS

4. Australia v West Indies, Perth, 1992

Curtly Ambrose often features in these lists; he’s a difficult man to ignore. Australians still speak in hushed tones about what Ambi did to them at Perth in 1992. This was the famous series when West Indies fought back to tie the rubber with a one-run win at Adelaide, after Lara had made his maiden century (277 at Sydney) and Warne had taken his first five-fer (7-52 at Melbourne). But the decider was decidedly one-sided, and this was all due to Ambrose, a brooding joker who let his bowling do his work, and who enjoyed nothing more than playing his bass while hiding behind the immortal line: “Curtly talk to no man.”

It comes to something when a man’s final figures of 18-9-25-7 don’t do justice to his performance, but in Curtly’s case he actually took his seven wickets in a single spell, on day one on a fl at but typically deathly Perth strip, for the cost of ONE whole run. So that’s seven wickets, for one run. Seven for one. 7-1. It wasn’t so much that Australia collapsed, more that Curtly hosed them down, one after the other. Boon, M Waugh, Martyn, Border, Healy, Hughes, Angel: all for a run. Australia sloped from 85-2 to 119 all out.

It wasn’t intimidating. It wasn’t chin music at full blast. It was controlled back-of-a-length seam bowling from one of the best bowlers who ever played the game (and undoubtedly the greatest who ever got his mum to ring the village bell in the marketplace every time he got a wicket).

In reply, All Out Cricket’s favourite cricketer, Lord Keith Arthurton of Nevis, made 77, Ian Bishop took a six-fer in the second dig, and West Indies could hold on to their crown for a few more years.

– PW

3. England v Australia, Adelaide, 2006

No one day in English cricket memory conjured up as much gut-wrenching pain. The first Test loss had been banished as a distant memory by Collingwood and Pietersen – the two men in the England side who had the passion, guts and skill to right the wrongs of Brisbane.

Australia, as we now know, counter attacked well, clawing run by run, minute by minute until they were within touching distance of England’s first innings 551. All that was left was for England’s restored fight and pride to forge a positive end to the Test, and take a draw and a 1-0 deficit to Perth. All we needed was more of Colly’s bastard fight (which we got) and more of KP fighting fire with his own fire (which he tried), only for Warne to fizz a leg-break around his arcing slog-sweep and pin back his off-stump. That moment, that seminal moment, was when it all fell apart.

From 69-1, Englnd lost their last nine wickets for 60 in 42 harrowing overs, to be all out for 129. Game over. 2-0, spirit shattered. We know the rest.

– WS

2.

Beaten at home by New Zealand in 1999, by South Africa the following winter, and then emphatically outplayed in the first Test at Edgbaston against one of the West Indies’ weakest post-war touring teams, when England prepared to bowl again in the second match at Lord’s, staring at a first innings deficit of 133 having just limped to 134 themselves (a recovery, considering they were 9-3), it’s fair to say that English cricket was well on the road to oblivion. 31 years since a series win against West Indies, 13 years since they won the Ashes, England’s past cast its shadow over every ball bowled that day.

The West Indies, meanwhile, were clutching to theirs. No longer the force they once were and nursing Curtly and Courtney through their final duties, when Andy Caddick took the new ball on Friday afternoon and dug one in short and wide – a nice fat four ball – in the fourth over of the innings, the West Indians were desperate to take full toll. Sherwin Campbell duly carves it over the slips and down to third man. It is seriously travelling, but then so is Darren Gough, who pelts round the boundary and dives full length to take a ridiculous two-hander at full tilt before rolling at least 20 times on the turf. It’s one of the great catches, not least because it suspends the flow of mediocrity that was discolouring England performances. 6-1.

Andrew Caddick weaved his magic all over the Windies

Andrew Caddick weaved his magic all over the Windies

So Caddick gets to work. Nasser Hussain, his captain, later said, “Caddick decided to get out of bed this morning.” Mercurial, diffident, gifted, that day Caddick was irrepressible. In the same over he gets one to climb at Hinds from a good length: 6-2. Then Gough finds the edge of Griffith’s bat: 10-3.

The big one comes next, with Lara fending Caddick to gully: 24-4. Shiv Chanderpaul, Ridley Jacobs (after a counter-attacking 12) and Jimmy Adams are the next to fall, and suddenly it’s 39-7. Dominic Cork cleans up the tail, and after 26.4 overs and 128 minutes, West Indies are all out for 54, and Caddick has 5-16, Gough 2-17, Cork 3-13; Ridley hit two fours – half his side’s full quota.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tAne308rEyo

And yet England still needed to win the thing. Chasing 188, they were 95-1, before Courtney kicked into gear. A young lad called Michael Vaughan nicked off and, guess what, the England middle order collapse swiftly followed. Although it was anyone’s at 160-8, the critical blow was struck by that arch attention seeker Cork, who cut the tension by swatting a long hop by Franklyn Rose high into the Mound Stand.

Cork’s 33 not out was one of the most significant contributions to English cricket at the time. Without it they would have lost, gone two-nil down, and would have been too crushed to mount a comeback. History tells us that England would eventually triumph 3-1 and become a rather good cricket team, and the old powerhouse would inexorably continue what they’d started at Lord’s; astonishing and sad to note, a West Indies victory against South Africa, at PE in December last year, was their first overseas win since that first Test in 2000.

– PW

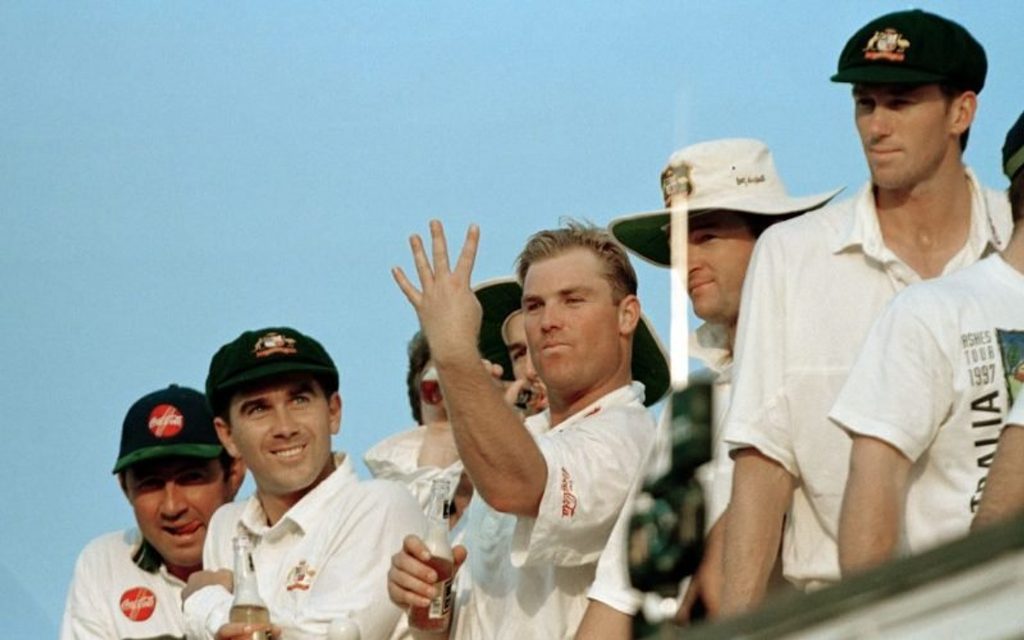

1. England v Australia, 1997

In the naughty Nineties, the words ‘Middle’, ‘Order’, and ‘Collapse’ were as synonymous with English failure as ‘Recession’, ‘John’, and ‘Major’.

These were words with enough clout to hang whole jokes on, and not just to serve as comedy of errors slapstick, but as actual jokes. Eerily, Major himself would work a cracker into his after-dinner routine about a mystic, a broken leg, and a gypsy wish to be spared another England Middle Order Collapse. Oh, how the corporates rolled in the aisles.

The EMOC reassured a fragile national psyche. In an age of sleaze the collapse was something we could trust. If nothing else it stopped us getting too excited. And it taught us the important life lesson that nothing’s ever as good as it seems, that misery is just a loose drive away. A deal was struck. We would watch our boys with cynical amusement, and in return, they would be sure to cave in as one when the going got rough. We had an understanding, which naturally extended to any visits from Australia – on those occasions the EMOC would faithfully be deployed every fortnight for a whole series.

But we were still unprepared for the heady summer of 1997. After years of downbeat repetition, for a brief and baffling moment it looked as though the twin totems of visionary new government and adhesive middle order would replace the established patterns of English life.

Okay, so maybe the effect of bleary Blair’s morning pose on May 2, complete with rictus kids and orchestrated cuppa, didn’t actually make our cricketers play better. But for a time, you can’t deny it, there was a strange whiff of optimism drifting over the country, and a month after the landslide, in the first Test of the summer, England caught the mood by thrashing Australia at Edgbaston.

This was the game when Australia approached lunch on day one of the series with the scoreboard reading 54-8; this was the game when England replied to Australia’s 118 with 478 despite being 50-3, and when middle order chancers Hussain and Thorpe put on 288 for the fourth wicket to smash the fabled EMOC out of sight. This was the game when Alec Stewart hit the winning boundary on day four to seal a nine-wicket victory for England’s first meaningful Ashes win in seven years. Harold Wilson once cheekily pointed out that England’s football team only wins the World Cup during a Labour government; no doubt Blair’s mandarins were readying a press release connecting Ashes success with New Labour.

Australia retained the Ashes – again

Australia retained the Ashes – again

A fortnight later the teams rocked up at Lord’s. England were full of it. And so was Glenn McGrath.

Remember McGrath? Pretty good on a featherbed, seriously good on a flat one, lethal on a pitch with life, and gothic at Lord’s? In all he took 26 wickets in three Tests at HQ, averaging 11 runs per scalp, and in this match he took 8-38 to rout England for 77. There was no EMOC here, just a systematic dismantling of England’s belief in themselves, from top to bottom, nick after snick after three-card trick.

Oddly England drew this match. It rained for over half of it, and they escaped. Positives were sought and found in press conferences. But we knew. We knew, in our hearts, what was to come. 77 all out. Eight wickets for 38. It said it all. There would be no third way, and no second resolution.

In the next match at Manchester, Steve Waugh duly makes a pair of cussed hundreds and Shane Warne takes nine wickets. In the fourth at Leeds, Australia win by an innings. In the fifth Test at Nottingham Australia’s top five all make half-centuries and England lose by 264 runs. Just for old time’s sake, that match features a good old EMOC, the home side losing its last six wickets for 65. This collapse lasted a whole summer. After the honeymoon of Edgbaston, hyped up too high and drunk on the promise of power, we’d cheered and hollered and waved our flags, and dreamt that the big beasts had gone. Well, they hadn’t.

Afterwards on the Trent Bridge balcony Warne does that wobbly ban-worthy dance with a stump, and that, with brutal clarity, is that.

And the legacy? Another eight years of Aussie rule makes it an 18-year stranglehold on power. The public are tired, apathetic; it would need a popular uprising, led by a serf from Preston, to awaken them.