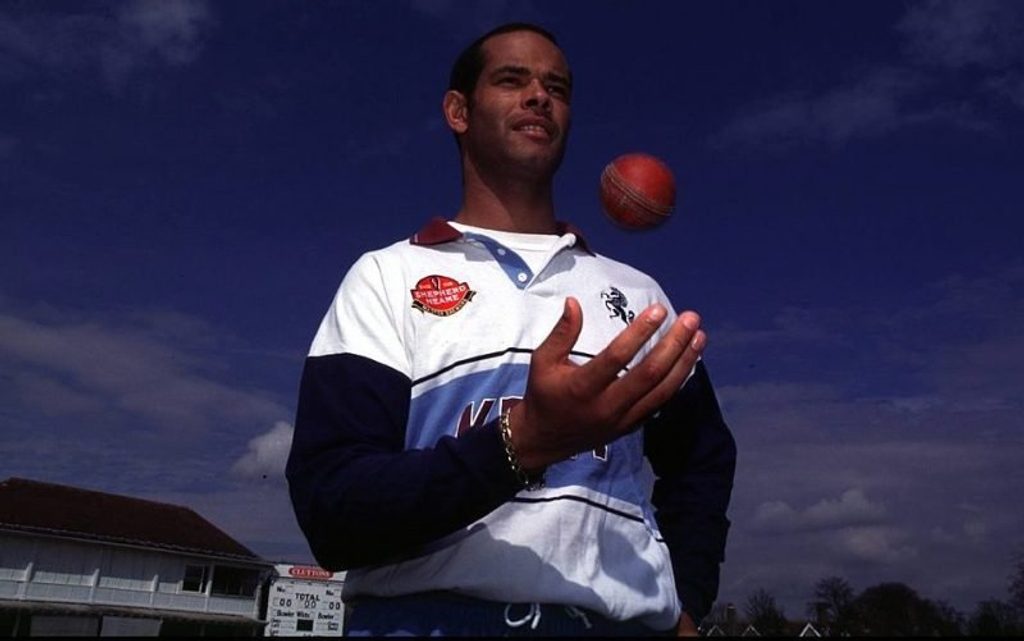

At his best, Dean Headley was irresistible. But injury restricted him to just 15 Tests and cut him off in his prime. Jo Harman looks back on the career of the former England fast bowler who paid the price for never saying no.

It’s December 29, 1998, and we’re deep into the longest day in Test history. Australia, already 2-0 up in the Ashes, are cruising to victory in front of a bumper crowd at the MCG – 103-2 in pursuit of 175 to clinch the series.

An outrageous one-handed grab by Mark Ramprakash at square-leg to dismiss Justin Langer appears to only delay the inevitable, as the final session – extended to make up for a washout on day one – rolls on and on. Steve Waugh joins his twin at the crease, determined to finish the job that evening. Then something extraordinary happens.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365.

Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way.

Mark Waugh is the first to go, a thick edge flying to a tumbling Graeme Hick at second slip. Then Darren Lehmann, Ian Healy and Damien Fleming follow in rapid succession with the score stuck on 140. Suddenly, Australia are going nowhere. They’ve lost four wickets in the space of 24 deliveries and Dean Headley, who had earlier dismissed Michael Slater, has taken all of them.

Leaning on his bat at the non-striker’s end, Waugh watches on, his expression inscrutable. He and the debutant Matt Nicholson take Australia to within 14 of victory, and at 7.22pm Waugh decides to claim the extra half hour. Alec Stewart protests – the session has already been going for three hours and 50 minutes by this point – but Headley, who’s almost two hours into his second spell and getting the ball to reverse, steams in yet again and gets his reward, finding Nicholson’s edge to reignite the contest.

Headley is undeniably the game-changer though, receiving the Player of the Match award for his Test-best figures of 6-60, including a marathon second spell of 10-3-26-5. Richie Benaud describes the final session, which eventually concludes after four hours and three minutes, as “one of the most exciting and dramatic things I’ve seen in Test cricket”.

A few days later, Headley bowls even better at Sydney, claiming eight wickets in a losing cause and taking his overall tally to 35 in six Tests against Australia. England coach David Lloyd says the Kent fast bowler has “come of age” on the tour: “This series will give him the platform to go and do great things for us.”

But Headley will play only 14 more first-class matches, retiring from the game in 2001 after a mysterious loss of form which is belatedly revealed to be the result of a chronic back injury. English cricket is left to lament what might have been, with Headley’s career serving as a cautionary tale.

***

“Dean was a real thoroughbred,” says Lloyd now. “Effortless, completely effortless. And a consistent 90mph bowler. He was a fantastic bowler to left-handers and had an amazing engine. But his asset was his pace, from nowhere. Someone like Mark Wood has got to strain every sinew to bowl fast, but not Dean Headley. Like Jofra Archer, it would just come out and you’d think, ‘Crikey where’s that come from?’ And he just kept coming.”

“He was accurate and he was fast,” says Dave Fulton, who played alongside Headley at Kent for seven seasons. “He was a lot slipperier than people realised. He was always at you and he’d get the ball to nip back in. He didn’t have much of a front arm, so he could be tough to pick up, but he had a lovely approach to the crease – very athletic and languid; almost a Michael Holding-type run-up. And he could reverse-swing the ball as well, so he had a lot of attributes. If it hadn’t been for his back, who knows what he could have accomplished.”

Despite his raw talent and pedigree (his grandfather, the great George Headley, and father Ron both represented West Indies) Headley’s first steps in the professional game were far from straightforward. Released by Worcestershire as a teenager, it had taken an intervention from Clive Lloyd, a close family friend, to re-energise his career – first securing him a contract at Leycett in the North Staffs and South Cheshire League and then trials at Derbyshire, Middlesex and Somerset. Receiving offers from all three, Headley opted for Middlesex, taking a five-for on his Championship debut against Yorkshire in 1991 including a wicket with his first ball. “It’s all downhill from here,” said his teammate Angus Fraser as they left the field.

After two hit-and-miss years at Middlesex he turned down a contract extension and moved to Kent, where his career took off. A haul of 44 first-class wickets in 1995 led to his selection for the England A tour of Pakistan that winter where, under the captaincy of Nasser Hussain, he bowled relentlessly in unforgiving conditions.

“It was just ridiculous the amount of overs I bowled,” Headley tells Wisden.com. “I bowled 45 overs out of 110 in an innings [of a first-class match against Pakistan A]. It wasn’t sensible but when you’re trying to make your way in the game, you’re not the best barometer. If your captain comes up to you and says, ‘How many have you got?’ I’d always go, ‘How many do you want?’ It probably cost me in the end.

“At Worcester there were a couple of people who labelled me a shirker, and actually told other people that I was a bit of a prima donna and didn’t want to play. And that really hurt me. I knew that I wasn’t a shirker, I’m definitely not a prima donna. Quite often when I left the field, I’d be broken. If I could play, then I’d play. Today it’s not necessarily the player’s choice.”

“When you looked Dean in the eye, he always wanted to bowl more,” wrote Hussain in his autobiography. “So many people are not like that. When I was on the ‘A’ tour in Pakistan, the contrast between Headley and Ed Giddins was pronounced. Whenever I asked Ed if he wanted another one, he had to know if Dean was having one, because he felt he had to do what his supposed rival for a Test place in the future was doing. Headley didn’t care what anyone else was doing. He just wanted the ball. It’s a tragedy that injury stopped Dean playing a bigger part for England.”

Headley took 5-109 in that epic spell at Peshawar (and 25 wickets at 15 across the tour of Pakistan) and would have had six but for Nick Knight shelling Asif Mujtaba at slip – a missed chance which would have given him a hat-trick in the very first over of the match.

With 19 wickets from three Tests, Headley was England’s most consistent bowler in the 1998/99 Ashes series

With 19 wickets from three Tests, Headley was England’s most consistent bowler in the 1998/99 Ashes series

He wouldn’t have to wait too long for more hat-trick opportunities though. Across the 1996 summer he took three of them, becoming only the third player – after Charlie Parker in 1924 and Joginder Singh Rao in 1963 – to achieve the feat in a first-class season.

After dismissing Kim Barnett, Chris Adams and Dean Jones in successive deliveries of Kent’s Championship fixture at Derby in July, Headley did the same to Tom Moody, Reuben Spiring and Vikram Solanki against Worcestershire in his very next match. When he removed John Stephenson and James Bovill in consecutive balls during Hampshire’s visit to Canterbury the following month, it wasn’t just the bowler who realised he was on the brink of history as Simon Renshaw, the No.11, took guard.

“There were a lot of not-outers at that time but Ray Julian was a good umpire because he gave people out when he felt they were out,” says Headley. “Ray said to me, ‘This will be a world-record, won’t it?’. So I said, ‘It would be great to be part of that, wouldn’t it Ray?’ I hit him on the foot. Gone. No complaints.”

Headley and his teammates celebrated by re-enacting Chelsea footballer Roberto Di Matteo’s trademark goal celebration, sliding across the turf in the shadow of the old lime tree at St Lawrence and raising an arm in the air.

Incredibly, the match featured another hat-trick, Kent quick Martin McCague marking his own three-in-three in Hampshire’s second innings by lifting his shirt over his head and running around wildly à la Middlesbrough striker Fabrizio Ravanelli. “We called it the Rava-belly,” says Headley. “Martin was a big lad.”

***

Headley made his ODI debut against Pakistan in the midst of his hat-trick heroics but had to wait until the following summer’s Ashes series to receive his Test cap. Following in the footsteps of his grandfather and father, he become the third Headley to play Test cricket – the first instance of three generations of the same family doing so.

He made an immediate impact, terrorising Australia’s left-handers to take eight wickets on debut at Old Trafford, and he continued to make a positive impression on the winter tour of the Caribbean. He had a quieter summer in 1998, playing a solitary Test against South Africa, but won his place back on the 1998/99 Ashes tour, paving the way for his show-stopper at Melbourne.

Headley returned home “on top of the world”, only to slip on a training mat in pre-season and suffer a seemingly innocuous injury. From there, things began to go badly wrong.

“That was a horrendous year,” he recalls. “I just didn’t feel right, but I had no pain. John Wright [then Kent coach] got stuck into me massively, telling me I needed to pull my finger out – that I’d gone to Australia and done well and now I was ‘Billy Big Bollocks’. That there was nothing wrong with me. But I had no snap, I couldn’t get the ball through. I played two Tests that year and I promise you I didn’t know if I was going to bowl short, full, leg-side, off-side. Can you imagine that? Going into a Test match and trying to blag it.”

“I think in our dressing room at the time, people were too quick to criticise,” says Fulton. “It used to frustrate the hell out of me when people would say so and so isn’t trying, or he’s shirking it. Hold on a second, you’re not in their body. That’s what they live for and you’re suddenly saying he’s got too big for his boots or his injury’s not that bad. You’ve got to be very careful when you make those kinds of calls.

“I think there was a bit of tall poppy syndrome, too. Maybe there were one or two who were quite happy to bring him down a peg. Don’t get me wrong, Deano did have a confident aura. We’d go out of a night-time in Canterbury and there’d be a queue of people outside the nightclub chanting ‘Deano, Deano’. He used to like rocking up in one of those white Mercedes taxis and I’d be like, ‘Deano, it’s 300 yards, we can walk’. So he had a little bit of that in him but in terms of trying 100 per cent for his team, there was never any question. He’d bowl his heart out for his side.”

Headley averaged 39 with the ball in first-class cricket across the summer of 1999 and took figures of 1-115 at Old Trafford against New Zealand in what proved to be his final Test, but he was so highly regarded after his Ashes exploits that he was still picked to tour South Africa that winter.

“I got selected because Nasser had faith in me. I got out there and I hadn’t bowled for six weeks. I’d just been to the gym, getting myself physically fit, because actually I didn’t want to touch a ball. I’d gone mentally and I started believing some of the shit that people were talking about me.

Headley took 466 first-class wickets at 28.52

Headley took 466 first-class wickets at 28.52

“I came to nets, Duncan Fletcher is there [in his first series as England coach] and I’m just hoping I’ve still got it. I bowl the first ball, that’s alright. And then bang, I’m back again. I’m thinking, ‘Thank God, whatever it was is gone now’. I bowled for two days in practice and Fletcher was really impressed.

“Third day of practice, Chris Read is batting, and with the very last ball I go wide on the crease, angle the ball in and knock his off stump out of the ground with a yorker. And then I went, ‘Oh, my back…’”

Two days later Headley pulled up during a tour match and returned home, but it still took months before he got an accurate diagnosis. It was only when he was finally given a scan in April 2000 that it became clear he had been bowling with a cracked spine. “They said it wasn’t a new injury. I’d done it months before. When people realised I had these stress fractures, they knew what I’d been talking about.”

Even then, Headley was one of the first 12 players awarded central contracts by the ECB in 2000 but he was never able to get back on the park and retired the following year, with 60 wickets from 15 Tests and the 10th-best strike of any England bowler in history (minimum 50 wickets).

“The best thing that ever happened to English cricket was central contracts, to protect lads like Headley, lads like Chris Lewis,” says Lloyd. “They were special talents but they would be turning up after bowling 40 overs or more in a county game to then start a Test match. Bloody ridiculous. I would definitely say that the quick bowlers, like Headley, paid a price. We would be asking Kent, through [chairman of selectors] David Graveney: How fit is he? It was a messy process. You had to go through a third party, i.e. the county, to decipher how fit the bloke is.

“Look at the longevity of James Anderson, who is monitored. Whether people like it or not, if a player gets into the red zone, it’s time to come out. Because you’re risking injury more and more. I would say that they’re now managed properly. Central contracts have made it really professional. England are now directly looking after the welfare and fitness of the player.”

Whether a central contract would have allowed Headley to fulfil his potential on the international stage is a moot point, but it certainly would have given him a better chance. Now working as director of cricket at Stamford School, he prefers to focus on what he was able to achieve in his brief but eye-catching England career, rather than wondering what might have been.

“I was extremely privileged to have the chance to play in the places that I did, with the people that I’ve met, the friendships that I’ve formed, the battles with people that I’ve had. I don’t see how you can look back with ifs, buts and maybes.

“People say, ‘If you’d carried on playing you’d have got 200 Test wickets’. Well, I didn’t. I’ve got 60. But 60 is better than none. I realise that it could have been more, but it could easily have been a whole lot less.”