Richard H Thomas examines English cricket’s complicated relationship with the leg-spinner, the species known to deliver the game’s noblest art.

First published in 2014

First published in 2014

“Can he spin it?” we would ask amid rumours of a new leg-spinner. Usually he could. “Can he control it?” asked the selection committee; usually he couldn’t. Thereafter he was treated more suspiciously than an unexploded doodlebug. Fast bowlers are sweaty artisans with hammers. Medium-pacers are architects with precisely sharpened pencils. Contrastingly, leg-spinners are eccentrics in the garden shed. They might invent eight variations of googly or blow the roof off.

When the leggies come on, crowds are all nudges, elbows and eyebrows – ready, says Simon Briggs, for “what improbable feat might follow”. When Denzil Batchelor first saw Kent’s Doug Wright and his brisk, bouncy run-up he whistled like “a sailor whistles at a new wife in a new port”. But, as Stephen Brenkley observes, if some “chubby blond kid” can became one of the most influential cricketers of all time, leg-spin “can take you places”. Gideon Haigh after all, reminds us that it accounts for history’s two most famous deliveries – Eric Hollies’ googly to Bradman in 1948 and Shane Warne’s outrageous ‘ball of the century’ in 1993. The incentive is developing a novelty batsmen may find unfathomable; the charges against are that leg-spinners are eccentric, erratic and unsuited to English green tops. With fame, fortune and diamond ear studs waiting, there will always be a few choosing to strengthen their wrists instead of their fingers.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way.

But who and where are they? Four specialist English leg-spinners have played just 24 Tests in the last 50 years. When the last wrist-spinner took five-fer, notes Mike Selvey, Harold Macmillan was prime minister. Derek Abrahams describes them as common as “honest politicians”, their wickets, according to Lawrence Booth, rarer than “Australian sympathy for the Poms”. If England’s relationship with KP has been vexatious at least it was long-lasting; its relationship with leg-spin has been equally troublesome but far more fleeting.

Charges of eccentricity are unfounded; leggies aren’t flaky, they’re optimistic and dogged. At Lord’s in 1900, Bernard Bosanquet’s newly-invented googly claimed its first victim: Leicestershire’s Samuel Coe was stumped off a delivery that bounced four times. Through dedicated resolution, the googly survived. Tommy Greenhough had his Lancashire contract cancelled after falling 40 feet in an industrial accident aged 16 – injuries to his wrists and ankles were so severe a cricketing career seemed inconceivable yet he recovered to play Test cricket. Eric Hollies had an “innate cheerfulness” wrote Michael Billington, and Walter Robins epitomised the brotherhood’s pluck. “There was something about his cricket,” concluded RC Robertson-Glasgow, suggesting “half-holidays and kicking your hat along the pavement”. Ian Salisbury, for so long almost England’s only exponent reports the value of having “a point of difference” but that during his apprenticeship it often occurred he might’ve picked “something a little easier…” But he, like all the others, stuck to his task.

The next charge is that when the wheels come off, the wagon doesn’t come meekly to rest on the hard shoulder. At Adelaide in 2012, South Africa’s Imran Tahir recorded excruciating match figures of 37-1-260-0. When Victoria posted their record 1,107, leg-spinner Arthur Mailey took most of the tap – a jaw-dropping 4-362. On Bryce McGain’s toe-curling Australian debut at Cape Town in 2009, his first spell of 11-2-102-0 and match figures of 18-2-149-0 “did not flatter”, according to Vic Marks. It would be nice to report that he bounced back but when leggies implode bouncing is not the issue; they can’t stop bowling full tosses.

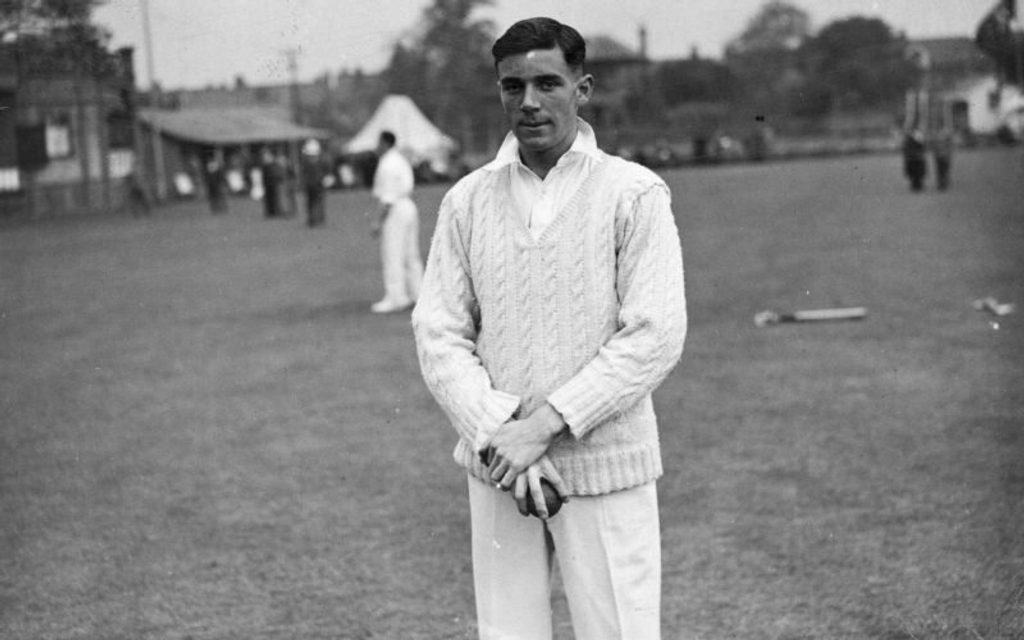

Of the 10 most expensive Test match figures, leg-spinners account for all but two. Notions they are untidier than undergraduate dormitories are at least plausible. Most clubs have their own leg-spinning folklore, usually featuring discourses of profligacy. We knew one that suffered from a painful affliction called “leg-spinner’s neck” – a permanent crick caused by years of jerking his head to watch the ball sail into the next postcode. The “expensive” tag sticks; Arthur Mailey bowled like a “millionaire” and there is consensus too, regarding Doug Wright – “unplayable” one day and “frustrating” the next according to Brenkley; “engaging” yet “exasperating” according to David Foot. David Frith describes Wright as “quiet” and “calm” with “a touch of genius”, but also describes his wickets as “costly”. Such was his occasional waywardness for Kent, Colin Cowdrey described it as akin to playing with 10 men.

Of those who took more than 100 wickets for England (there are 44) Wright’s are the second most expensive. In his defence, he was unlucky. Batchelor recalled his best deliveries beating the batsman, but also “sadly missing the stumps”. Wright himself claimed in his finest ever over he beat Bradman twice. The rest went for boundaries. ‘Father’ Marriot, also of Kent, took 11-96 in his only Test for England and was, according to Allan Massie, annoyed by “the fallacious notion that a wrist-spinner could not bowl as accurately as any other type of bowler”. The statistics suggest this may not have been as fallacious as he claimed, but they are not inherently expensive; England’s five most successful wicket-taking Test leggies have better economy rates than Steve Harmison, Darren Gough, Matthew Hoggard, Mitchell Johnson, Brett Lee and Dale Steyn.

Doug Wright is the only English leg-spinner with 100-plus Test wickets (108)

Doug Wright is the only English leg-spinner with 100-plus Test wickets (108)

They may be scarce nowadays, but until the Seventies, numerous county leg-spinners took bucketfuls of wickets and regularly dismantled batting line-ups – a generation of home-grown twirlers, says David Frith, with “long, productive county careers”. The biggest of these achievers was the smallest of men and another Kent bowler – 5ft 2in Tich Freeman. In a career straddling the first war, he dismissed an astonishing 3,776 batsmen. In each of eight seasons between 1928 and 1935 he took over 200 wickets, and in the first of them, over 300 – the only bowler ever to do so. He claimed five in an innings 386 times and 10 in a match 140 times. Shane Warne did those things 69 and 12 times, respectively. According to RL Arrowsmith, Tich was “the greatest wicket-taker county cricket has ever known”. Most agree that he wasn’t as deadly in Tests, but 66 wickets in 12 matches is none too-shabby, especially with a strike rate, bowling average and economy rate all lower than Botham and Anderson to name but two.

Then there was Eric Hollies. Doing Bradman with a googly was no fluke; the week before he’d bowled him with a regulation leg-spinner but noticed The Don couldn’t pick the wrong ’un. At least at Edgbaston there is a stand named after Hollies to reflect the two decades of toil before and after that single delivery. Roly Jenkins of Worcestershire would beseech the ball to “spin for Roly” as he released it. Mike Vockins suggests he probably talked out as many batsmen as he bowled but there were plenty of both; county colleague Martin Horton remembered a dedicated bowler always refining his technique. Disliking batsmen sweeping him, Roly once wished horrible things on Bill Alley’s chickens. In addition there was Tommy Mitchell, Jim Sims and a legion of others, sometimes expensive but wicket-takers all. To the doubters now shouting “helpful uncovered pitches” only two words are needed to counter: Mushtaq Ahmed. “Statistically, romantically and emotionally,” according to Chris Adams, “the best player to ever pull on a Sussex shirt”. He took 459 wickets between 2003 and 2007. Ian Salisbury concludes that Mushtaq found the right club and the right pitch: “A slow, low one at Hove”.

In sum, it isn’t temperament, pitches or potency, and the case for habitual untidiness is moot. So why has our relationship with leg-spin never progressed further than smooching on the sofa? Between Salisbury’s last Test in 2000 and Scott Borthwick’s first in 2014, English leg-spin at the highest level comprised of 18 wicketless overs from Chris Schofield. Collectively, Tich Freeman, Tommy Mitchell, Eric Hollies, Jim Sims, Peter Smith, Roly Jenkins and Tommy Greenhough took 12,920 Championship wickets, yet altogether appeared in fewer Tests than Monty Panesar. Since the Sixties, the art has all but disappeared and little wonder; seemingly selectors trust them less than a toddler with an iTunes password. As a youngster, Salisbury turned to wrist-spin despite having “no role models and no one to watch”.

Goodness knows we’ve been taught enough hard lessons from Australia lately, but here we may have to take another. Aussie leg-spinners are as popular as beer in a barracks. Hordern to Mailey to Grimmett, O’Reilly to McCool to Benaud to O’Keefe to Higgs. This was a seamless, almost blue-blooded lineage. Then, the greatest of all – Warne, but overlapping with Stuart MacGill, who Frith suggests was almost Warne’s equal. One English leg-spinner took over 100 Test wickets; four Australians took more than 200. Australia’s top five leggies in the last 125 years took 1,524 wickets in 316 Tests, England’s top five took 327 in 91. Longstanding familiarity with the art has enabled Australia to develop their own and disarm England’s. Batchelor for example, reports that in Australia, Freeman was “all but powerless”. So used to such stuff were the Aussies, he wrote, “they’d developed footcraft” in self-defence “as fish developed gills”.

What. A. Delivery.

Adil Rashid proving it’s not just India who have a world-class wrist-spinner in their ranks.#ENGvINDpic.twitter.com/Iecb6E0C07

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) July 17, 2018

There was no deliberate succession of Australian leg-spinners, suggests David Frith, “but they were there, one after the other”. His compelling explanation is that while traditionally English cricket is more hesitant, Australian confidence abounds. While the English look for the leash, Australia give it the lash. When Tiger O’Reilly claimed the English never understood leg-spin “so they killed it”, he implicitly suggested every circumstance was loaded against it. He would have also meant, suggests Frith, that leg-spin needs daring – from bowlers, captains and selectors. Daring indeed, like saying “have a fifth” to Warne after four wickets in his first four Tests. Frith’s compressed analysis is that leg-spin expresses character and “Australians are by nature more adventurous”.

Moreover, in providing the ultimate role model of Warne, Australia may have further indirectly damaged English leg-spinning. Salisbury contends that Warne made it fashionable but remains the unreachable bar. He is an “outlier” and a “freak of nature”, argues Salisbury, and such was his uniquely sublime talent, he could bowl beautiful, controlled, leg-spin “ball after ball with his eyes closed”. It is unfair to measure everyone against the Warne yardstick, he suggests, noting that new batsmen are not instantly compared with Tendulkar or Lara.

Education and preparation are key now, claims Salisbury, implicitly contesting Tiger O’Reilly’s advice that when leg-spinners see coaches approaching they should “run for their lives”. Salisbury would agree with Tiger though, that self-sufficiency is critical. With England finally investing – though perhaps not enough – in specialist spin bowling coaching, the emphasis is on self-diagnosis and independence. Young spinners construct their own development manuals, says Salisbury, transcending the numerous different coaches and clubs encountered during development. The self-made templates are personal portfolios including scientific metrics, biomechanics, and tactical planning so that adjustments are made on the field, “not in the dressing room two hours later”. Recognising the hard realities of professional cricket, without such personalised blueprints, “that kid may not be bowling spin next year”, warns Salisbury.

In supporting every aspect of leg-spin, says Salisbury, bowlers become “their own best coaches” so that by their first Test matches all manageable performance elements are under control and heads are clear to focus on taking wickets. With the involvement of colleagues like Peter Such and Richard Dawson, Salisbury feels “things are heading the right way” but there is more to attend to than just wrists and fingers. Again emphasising English cricket’s underlying conservatism, he asserts that bowling coaches – most often pace bowlers – are generally nervous of leg-spin and should be more confident.

England cricket is currently showing some conservative tendencies and a mistrust of mavericks, so immediate embracing of Australian-style audacity looks unlikely. But, despite leg-spinning heroes being more global than local, in bowlers like Borthwick, Will Beer at Sussex, and, as Salisbury keenly points out, young Matt Taylor of Northants, there are reasons to be chipper. You must be “brave” as a young leggie, observes Stephen Brenkley. It requires “patience and practice” says Intikhab Alam. Toss in investment, science and trust and we have the answer. Then England’s affair with the noblest of bowling arts can move from smooching on the sofa to something altogether more exciting.