Bert Oldfield still ranks as one of Australia’s greatest wicketkeepers and was a key figure in the game between the Wars. After his death in 1976, Wisden published this tribute.

Oldfield, William Albert Stanley (Bert), died on August 10, 1976, aged 81

The Test match career of William Albert (Bert) Oldfield, MBE, might easily have finished before it had begun. A corporal in the 15th Field Ambulance, 15th Brigade, he was buried for several hours during the heavy bombardment of Polygon Wood in 1918 and was barely alive when rescued.

His great opportunity came in 1919 when the Australian Imperial Forces team (AIF) was touring England. Ted Long, the AIF wicketkeeper, had been injured, and C Kelleway needed a replacement for the match against Oxford University. Oldfield, who had been keeping wicket for the second of the two AIF elevens, was called upon, and he seized the opportunity with both hands.

He had learnt his cricket at Cleveland Street School in Sydney, where he showed promise both as a batsman and as a bowler. On leaving school he took up wicketkeeping, playing for Glebe in Sydney club cricket. In this match against Oxford, on May 29 and 30, 1919, Kelleway saw that here was a great wicketkeeper in the making, and Oldfield continued playing with the first eleven of the AIF, sharing the wicketkeeping with Long.

WA Oldfield’s Test career extended from 1920 until 1937, during which period he played in 54 Test matches for Australia, the same number that Herbert Sutcliffe played in for England. It is interesting to compare Oldfield’s record of Test match appearances with some of his contemporaries; Bradman (52) played in fewer Test matches than Oldfield, JB Hobbs (61) played in seven more. Other wicketkeepers, Strudwick (28) and George Duckworth (24), mustered 52 appearances between them; Leslie Ames played 47 times for England. Nowadays, with seven countries of Test match status, it is by no means uncommon for a cricketer to clock up ten or more Test matches in 12 months; whereas between the two wars, there was often a two-year gap between tours.

Oldfield played in the first three Test matches of the MCC’s ill-started 1920/21 tour, and came over as second wicketkeeper to Hanson Carter with Warwick Armstrong’s legendary Australians of 1921. In his account of this tour, (Wisden 1922) Sydney Pardon wrote: “Neither of the wicketkeepers was a Blackham, but Carter more than upheld his old reputation and Oldfield-the youngest player in the team-got on wonderfully well. It was quite a fitting compliment to give him his place against England at The Oval.”

Bert Oldfield in action for Australia against Worcester, circa 1934

Bert Oldfield in action for Australia against Worcester, circa 1934

Oldfield acquitted himself well in this Test match: in the England first innings of 403 for eight, the only extras recorded were three leg byes; the bowling of Gregory, McDonald, Mailey and Armstrong presented him with no problems.

It was in Gilligan’s exciting tour of 1924/25 that Oldfield became established as one of the great wicketkeepers. Australia won the first two Test matches. In the third Test, set 375 to win, England had scored 348 for eight at the end of the sixth day’s play, Gilligan and AP Freeman being the not out batsmen. On the next morning, nine runs were added before Gilligan was out for 31. Freeman and Strudwick took the score to within 12 runs of victory when Oldfield caught Freeman off Mailey-and the Ashes remained with Australia.

In the fourth Test match Oldfield provided unforgettable evidence of the astonishing speed of his reflex actions, when he stumped Hobbs, Woolley, Chapman and Whysall in England’s first and only innings. Hobbs was stumped off Jack Ryder, Woolley and Chapman off Mailey, and Whysall of Kelleway. Oldfield’s pièce de résistance was evidently the dismissal of Hobbs, when Ryder sent down an unexpectedly fast delivery that rose cap high: Hobbs, in avoiding the ball, moved momentarily out of his crease; Oldfield, meanwhile, in an amazing movement, had taken the ball and flicked a bail off.

In the fifth Test match Oldfield caught Hobbs in the first innings and stumped him in the second. In the first innings he caught him wide on the leg side off Gregory; this catch, says Wisden (1926), greatly influenced the course of the match – Australia in fact, went on to win by 307 runs. In the second innings, Oldfield stumped Hobbs for 13, the bowler being a newcomer to Test cricket named Clarrie Grimmett, who signalled his arrival by taking five for 45 in the first innings and six for 37 in the second. Four of Grimmett’s victims were stumped by Oldfield.

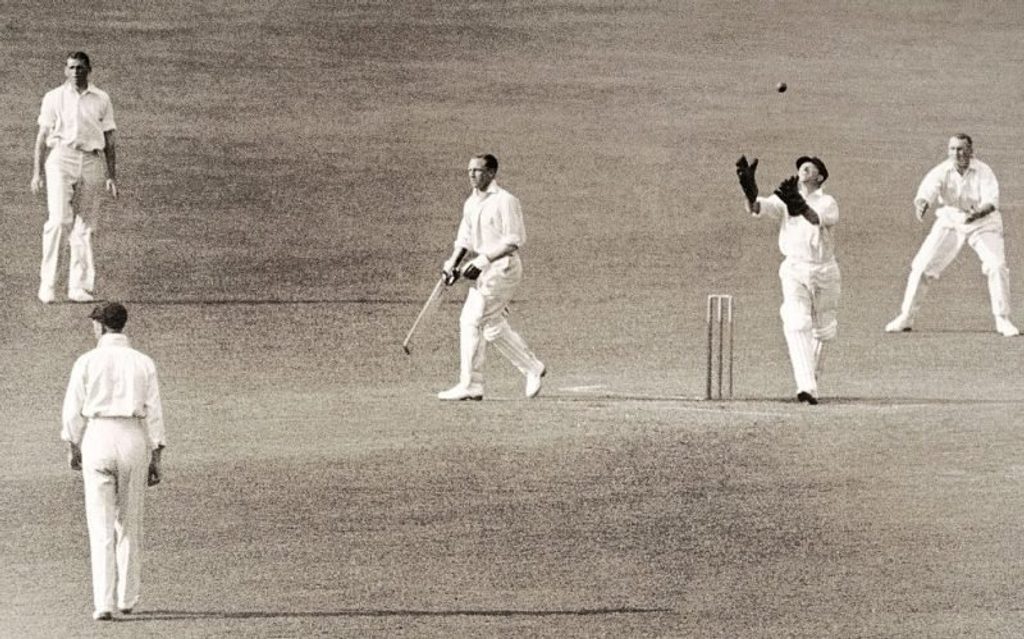

England’s Walter Robins is caught behind by Bert Oldfield off Percy Hornibrook at Lord’s, circa 1930

England’s Walter Robins is caught behind by Bert Oldfield off Percy Hornibrook at Lord’s, circa 1930

England regained the Ashes after 15 years, in 1926, when Australia was defeated in the final Test at the Oval. H.L. Collins, the Australian captain, said that he couldn’t remember Oldfield making a solitary mistake during the entire tour. Neat, quiet, and skillful said Wisden (1927), Oldfield showed himself as well-equipped a wicketkeeper as any side could desire to possess and completely overshadowed his deputy Ellis.

England’s first five innings in the 1928/29 series totalled 1912 runs, Oldfield conceding three byes. In 1930 the Australians came to England, bringing with them the incredible Bradman. Oldfield’s unobtrusive excellence behind the stumps was one of the factors that helped them to regain the Ashes.

Then came the MCC’s 1932/33 tour of Australia, the unfortunate bodyline series. Excitement reached its peak in a crescendo of anger in the third Test, pungently described at the time as the battle of Adelaide, when Oldfield, trying to duck a cannon-ball delivery from Larwood, was hit on the head, and carried unconscious off the field. His comment on regaining consciousness was typical of Oldfield: “My own fault.” Later, when Larwood settled in Australia, the two became the closest of friends.

Australia toured England in 1934; Oldfield’s wicketkeeping was as good as ever, and, as usual, he rendered good service in the lower half of the batting order. His last game against England was in the fifth Test at Melbourne, in 1937, when Australia, having lost the first two Tests, came up from behind to win the match, and the Ashes. His farewell performance in a Test match was highly successful; he sent back Barnett, Allen and Voce in England’s first innings and did not give away a bye in either innings.

Altogether Bert Oldfield played in 38 Tests against England. Ten of his eleven matches against South Africa and all five against the West Indies were played towards the close of his career, so it is chiefly in the matches against England that he will be remembered. There can be no doubt that he was at his peak in the 1924/25 series against Gilligan’s men; and in the 1926 tour of England.

Altogether in his 54 Tests matches, his bag was 130 dismissals; he made 78 catches and stumped 52. The 52 stumpings are a record for Test match cricket.

Percy Freeman is caught behind by Bert Oldfield off Arthur Mailey at the Adelaide Oval – the moment that clinched the 1924/25 Ashes series for Australia

Percy Freeman is caught behind by Bert Oldfield off Arthur Mailey at the Adelaide Oval – the moment that clinched the 1924/25 Ashes series for Australia

Bert Oldfield was small and wiry, with a quiet sense of humour and a genius for making friends. He had wonderfully quick reflexes, and, as an acquaintance said, a mind like a compass needle. He was neat, efficient and unobtrusive in his movements. You never knew he was there until he had you out said CG Macartney. Not for Bert Oldfield the raucous appeal.

Once, in a Test match, Strudwick appealed for a catch at the wicket against Oldfield. The umpire said not out. Strudwick recalled that Oldfield, who knew he had touched the ball, walked.

Neville Cardus has written of the apparent reluctance with which he dismissed his victims. J.H. Fingleton said that if he congratulated Oldfield on a brilliant piece of stumping, the latter would look embarrassed and then say quietly, “It’s nice to get them, isn’t it?” “He was a real gentleman on and off the field,” said Harold Larwood.

Oldfield took the fliers of Gregory and McDonald and the googlies of Mailey, Grimmett, O’Reilly and Fleetwood-Smith. Unlike the blood and iron wicketkeepers of the old school, he didn’t keep raw meat in his gloves: a more fastidious craftsman, he used two pairs of inners and finger stalls: even so, the expresses of Gregory and McDonald left their mark.

His teammates nicknamed him Cracker – a tribute to his crackerjack elasticity and to his badinage. In later years, he loved talking cricket, at his house in the Sydney suburb of Killara, or in his sports shop in Sydney. Betty Snowball, who kept wicket for England in the first women’s Test match between England and Australia in 1937, was introduced to him at Sydney in 1948, and remembers with delight the enthusiasm with which he chatted about every aspect of the art of wicketkeeping.

It was in keeping with his enthusiasm for cricket that in his later years he promoted the game in Ethiopia; and in 1976, with Larwood, he flew to Hong Kong for the opening of their new cricket ground. Tiger Smith, in his 91st year, the oldest surviving cricketer of England-Australia Test matches, who first kept wicket for England in 1911, considers Bert Oldfield and Dick Lilley the two greatest wicketkeepers that have ever played. In particular he refers to “an enthusiasm even more important than dedication.” Strudwick himself placed Evans, Oldfield, Cameron and Lilley equal top; Gilligan placed Oldfield first and without an equal.

The game has produced some great wicketkeepers, especially from England and Australia; there is little doubt that pride of place should go to the quiet Australian from Killara, who might so easily have found an unknown grave in the bombardment of Polygon Wood.