The news that Alastair Cook was to be knighted in the New Years Honours list was celebrated widely, though not everyone was pleased.

However, even the most curmudgeonly were surely at least a little happy that Sir Chef’s anointing brought the number of Englishmen knighted for services to cricket up to a prime 11, allowing for a semi-coherent team to be formed out of those honoured. It may be heavy on openers, light on bowlers, and with a few too many deceased than is ideal, but there is surely no team that could match this for chivalry.

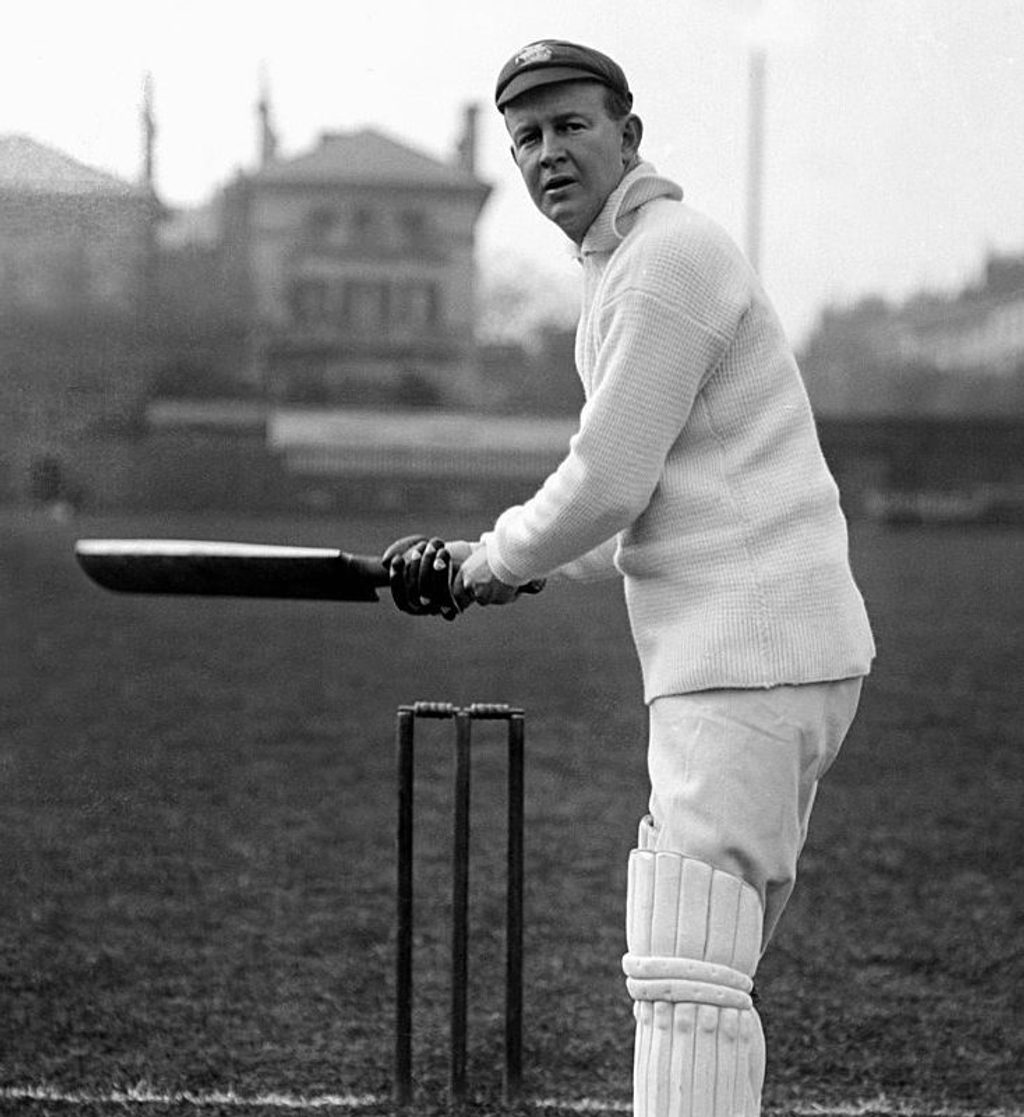

No.1: Sir Jack Hobbs

The most prolific run-scorer cricket has ever known. His 61,760 first-class runs and 199 first-class centuries are marks that no one is likely to even reach half of again. He played until he was into his fifties, and is one of only two players to be selected as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year twice. Hobbs was the first professional cricketer to be knighted, and you can’t say he didn’t earn it.

No.2: Sir Len Hutton

Judged alongside Hobbs as one of the two finest batsmen England have ever produced, it’s only right that they join each other in facing the new ball. Hutton’s 40,140 first-class runs at 55.51 are made all the more impressive by the fact that the majority of those were made with a shortened ‘harrow’ bat, necessitated by a badly broken arm during the Second World War.

No.3: Sir Alastair Cook

He might be the most prolific Test opener England have ever had, but there are no guarantees in this game, and the calibre of the two men above him means Chef is shunted to No.3. Not that a man who always put his country first will have any qualms, and it is of course where he made his century on Test debut. Having turned 34 a day before he was knighted, Cook is England’s youngest ever cricketing Sir, beating Hutton to the mark by six years.

No.4: Colin Cowdrey, Baron of Tonbridge

One of two to be awarded a peerage for their services to cricket – West Indian Learie Constantine is the other – Cowdrey was the first to play 100 Tests, and while he averaged close to 45 with the bat, he was noted as much as for his captaincy exploits. He exhorted his charges to chase down 215 in 165 minutes to secure England’s last series win against the West Indies for 32 years in 1968, before rolling up his trousers and manning the squeegee, as a frantic mopping operation gave Derek Underwood just enough time to level the series against Australia the very same year.

After retiring Cowdrey continued to contribute as President of the MCC, the ICC, and Kent, overseeing, among much else, the introduction of match referees and neutral umpires to international cricket. He was also a close friend of former Prime Minister John Major, who recommended he be made a Baron.

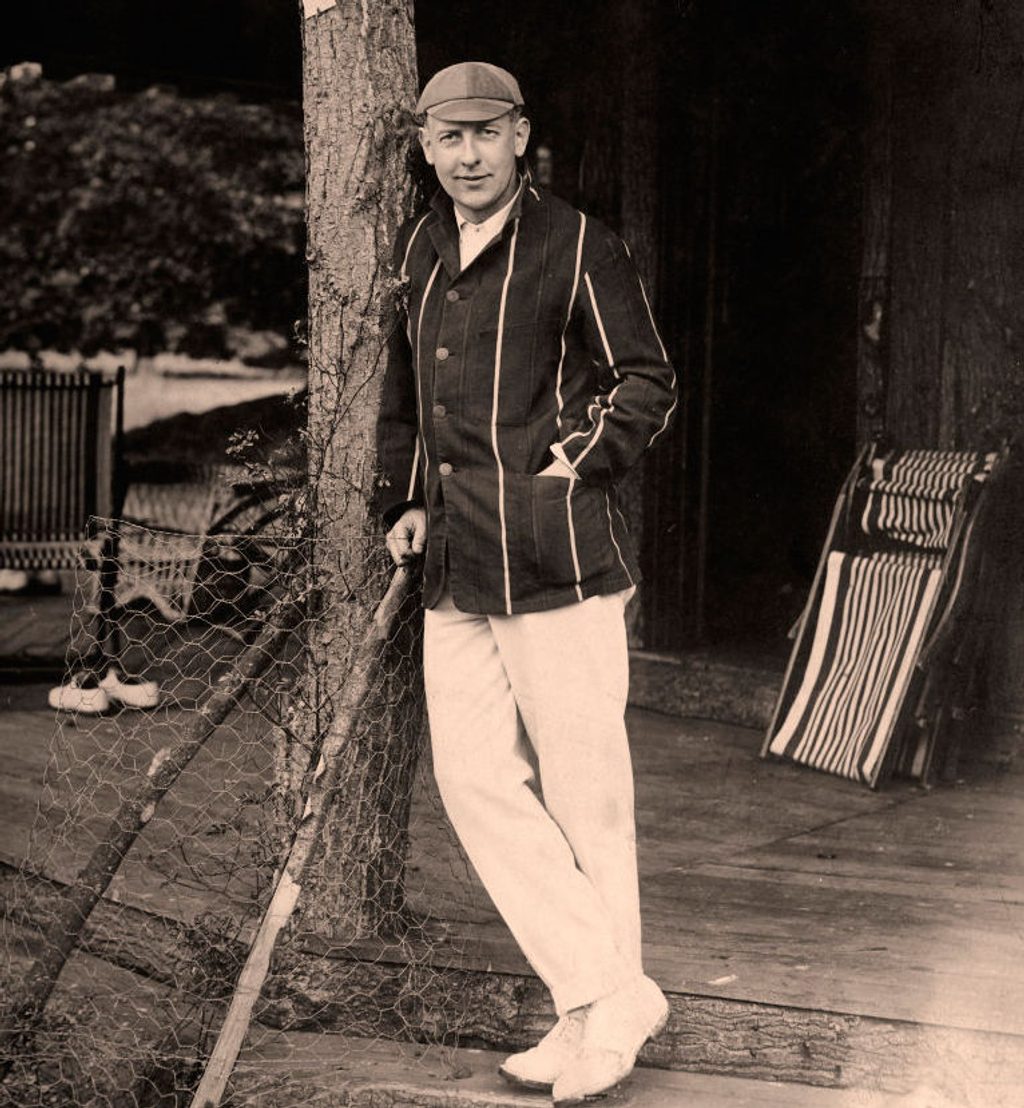

No.5: Sir Pelham Warner

‘The Grand Old Man’ of English cricket, ‘Plum’ was equally accomplished as a cricketer, administrator, and writer on the game. Born in Trinidad – his brother Aucher was the first to captain a combined West Indies side – Warner made his Test debut on Valentines Day in 1899, marking his bow by becoming as yet, the only Test debutant to carry his bat.

It still stands today as one of the great Test innings – England’s next highest score in the game was 29 and they defended 131 by 32 runs – and was his only Test hundred, though he managed 60 in first-class cricket and almost reached 30,000 runs. After retiring he was a tour manager, most notably during the ‘Bodyline’ series, a chairman of selectors, and President of the MCC. He also founded The Cricketer magazine.

No.6: Sir Francis Lacey

The first to be knighted for services to any sport, Lacey, with a first-class batting average of 33 and bowling average of 22, is our Botham. He only played 50 first-class games, since for most of his career Hampshire were consigned to the Minor Counties – his 323* against Norfolk remains the highest-ever Minor Counties score. His knighthood came more for his time spent as secretary of the MCC, playing a key role in helping to tidy up a previously ramshackle organisation.

No.7: Sir Gubby Allen

An all-rounder in every sense – apart from being a properly fast bowler, a capable batsman, and an excellent close fielder, Allen worked in the London Stock Exchange and in military intelligence during the Second World War. He refused to follow England’s ‘Bodyline’ tactics during the infamous Ashes series, but still came away with 21 wickets to his name, second only to Harold Larwood.

He continued in his refusal to be swayed as President of the MCC, when he played a key role in the D’Oliveira Affair, arguing against the all-rounder’s inclusion on cricketing grounds, and then asking the British government to intervene before South Africa’s visit to England in 1970.

No.8: Sir H.D.G. Leveson-Gower

Sir Henry Dudley Leveson-Gower, as he was almost never known – he was referred to by most as H.D.G, by his friends as ‘Shrimp’, and by American newspapers as ‘The Hyphenated Worry’ and ‘The Man with the Sanguinary Name’ – earned his knighthood more for his work as chairman of selectors and as administrator at Surrey and the MCC than for his exploits as a cricketer. His three Tests gave reaped a top score of 31. Were he around today, he might be more likely to win recognition as a leg-spinner; his 46 wickets at under 30 in first-class cricket are the kind of numbers that would pencil you in for a Test debut in an Ashes dead rubber.

No.9: Sir Alec Bedser

Bedser (left) with Ian Botham (right) in 1978

Bedser (left) with Ian Botham (right) in 1978

Alec and his twin Eric were inseparable – Alec once turned down a military promotion so the two could continue to serve together, and the pair remained unmarried and lived together until the latter’s death. The 10 minutes-younger Bedser twin enjoyed the more fruitful career, perhaps due to Eric plying his trade as an off-spinner after Alec won a coin toss deciding which of the pair would remain a seamer. Alec ended his career as the leading wicket-taker in Test cricket, and bowled a delivery described by Don Bradman as “the finest to ever take my wicket.”

“It must have come three-quarters of the way straight on my off-stump, then suddenly dipped in to pitch on the leg stump, only to turn off the pitch and hit the middle and off stumps,” wrote the Don. Post-playing, Bedser was a successful selector, though his part in the D’Oliveira affair, and his subsequent advocacy for the maintaining of sporting relations with South Africa during the Apartheid era were marks against him.

No.10: Sir Frederick Toone (wk)

The second man to be knighted for services to cricket, and one of two who never played a first-class game, though Toone did play high-level rugby union, scoring a try for Leicester in the first game at Welford Road – his hand-eye coordination earns him the gauntlets in this team. Toone managed three successive tours of Australia, the second of which, in 1924/25 came when there were growing concerns in Australia over the rise of communism, something Toone, a member of the British Fascists, would have been particularly worried about.

The Australian secret service were notified of Toone’s political allegiances, but still shortly after the conclusion of tour, evidence was uncovered that the British Fascists had established chapters in several Australian cities. As historian Andrew Moore noted, “it may be totally coincidental that the Australian chapter of the British Fascists was established so soon after the MCC tour,” and after his death Toone was reckoned by the Wisden Almanack as “the most capable manager who has ever represented [the MCC] on a foreign tour”.

No.11: Sir Neville Cardus

Born into poverty, Cardus earned his title for his work as a cricket and music critic. “Before him, cricket was reported,” wrote John Arlott. “With him it was for the first time appreciated, felt, and imaginatively described.” Cardus’ description of Wilfred Rhodes’ bowling is just one of many examples of his incomparable work.

“Flight was his secret, flight and the curving line, now higher, now lower, tempting, inimical; every ball like every other ball, yet somehow unlike; each over in collusion with the others, part of a plot. Every ball a decoy, a spy sent out to get the lie of the land; some balls simple, some complex, some easy, some difficult; and one of them — ah, which? — the master ball.”

Ian Botham – 12th man

It’s a rare team that can afford to leave out Botham, but with England’s greatest all-rounder knighted for his services to charity rather than cricket, it’s only fair that he carries the drinks.