Bob Willis, who died aged 70 on Wednesday, December 4, 2019, is remembered by Wisden Cricket Monthly editor-in-chief Phil Walker.

Bob Willis

1949-2019

With the sudden, jarring death of Bob Willis aged 70, the English game has lost a towering presence. Cricket is a smaller, quieter, less interesting place for his absence.

Willis, all 6ft 6in of him, was totemic in every respect. Principally, of course, he was a truly great fast bowler, whose legendary appetite for the struggle underscored his achievements across 15 years and 90 Tests, 325 wickets and more operations than all but a hundred men alive could live with.

After all of that, he became a media personality whose reading of the game was invariably so astute – and his delivery so droll – that he effectively patented the no-bullshit punditry persona that these days clogs up our TV screens. While it’s true, however, that many have imitated Bob Willis, it’s equally true that no one’s ever pulled it off like the man himself.

Bob Willis will be remembered as much for his punditry as his on-field exploits

Bob Willis will be remembered as much for his punditry as his on-field exploits

Like all the great pacemen, Willis dragged his body through the drudge. It was 1975 when he collapsed midway through a county game for Warwickshire, his knee chronically busted. It needed three operations to get it right. He spent a long period on crutches, then longer periods pounding the Edgbaston outfield to rebuild it. “It was horrible, tortuous,” he once told me, “but it worked.”

He separated his career into two halves – pre-1975 and after it. The early part of the decade had seen the Surrey schoolboy tread the tarmac at The Oval as understudy to Geoff Arnold and Robin Jackman, finding just enough purchase to make it onto the great Ashes tour of 1970-71 – where at Sydney he would make his Test debut – but not much else. With opportunities limited, he landed up at Warwickshire in 1972, though back then, such were the times, he had to sit out half a season, by way of punishment for daring to move clubs.

After 1975, Willis was reborn. With a remodelled action that offered him a bit more pace, he was duly recalled to the Test side, promptly taking eight wickets against the West Indies. “I went from one of the worst moments of my life to one of the best, all in the space of a few months,” he’d say.

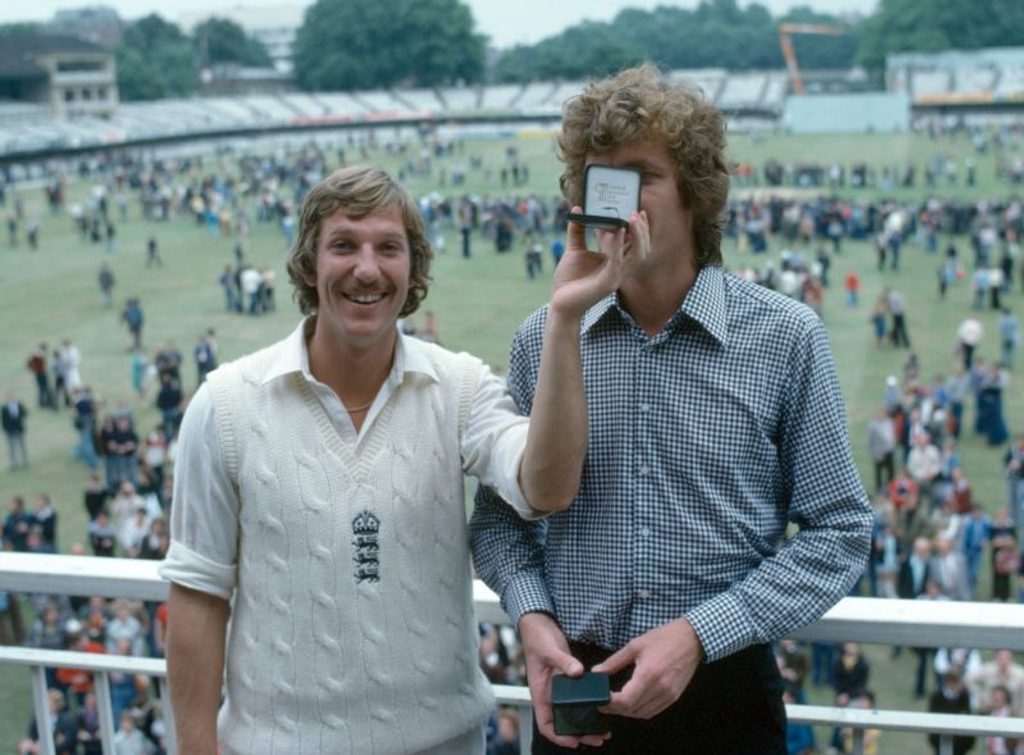

Ian Botham and Bob Willis display their series medals after victory over New Zealand

Ian Botham and Bob Willis display their series medals after victory over New Zealand

From that point on, the lionhearted windmill was unstoppable. By the turn of the decade, via a few twists and turns, Willis had turned himself into England’s most complete fast bowler of the time, the natural bridge between those other great fast-bowling mavericks, John Snow and Ian Botham.

Headingley ’81, of course, would seal the legend, though before it, Willis had feared his Test career might be over. His knees were giving him jip, he’d developed a serious no-ball problem, and with Australia already one-up in the series, the knives were sharpening in the press box even before England were forced to follow-on.

This was personally my first exposure to Bob Willis, via an old VHS videotape, Botham’s Ashes, in which Ian Botham smoked thin cigars by a fireside talking to Richie Benaud about the man they’d later christen “Bustlin’ Bob”.

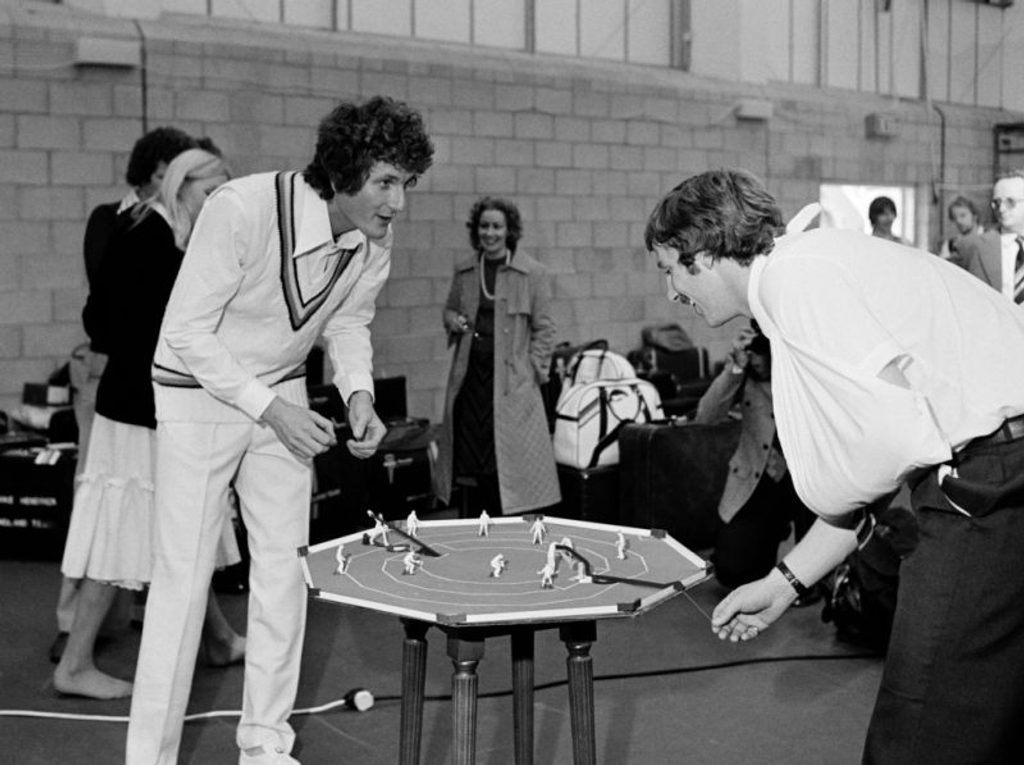

Botham nicknamed Willis ‘Bustlin’ Bob'

Botham nicknamed Willis ‘Bustlin’ Bob'

The story – that of Mike Brearley instructing him to come down the hill and not worry about overstepping the line, to bowl as fast as he possibly could and to hell with the consequences – would have been stirring enough. But the footage, of a crazed and evidently psychopathic madman with Einstein hair who didn’t speak or celebrate but just bowled like the end of days were upon us, a force of wild unchecked nature who would only open after the event with a punkishly sneering up-yours TV interview on the players’ balcony.

Naturally I was transfixed. This was my kind of cricketer, I thought; a feeling that only deepened when I found out that actually it wasn’t Einstein’s hair, but Bob Dylan’s. Ah, Bob George Dylan Willis. The folkie who went electric.

His career wasn’t quite done. He would yet do a stint as England captain, the last out-and-out fast bowler to take the job outright. He’d say he was pretty ambivalent about it – captaincy wasn’t his natural suit – but he led his country against Clive Lloyd’s unbeatable West Indians, as well as a tour to New Zealand which he was powerless to prevent being labelled forevermore as the ‘Sex, Drugs and Rock’n’Roll Tour’.

“Hmm, the relationship between players and the press rather changed after that one,” he’d later tell me wryly, though by that stage he was preparing to cross the floor himself. Act Two was ready.

In his later years on the telly, it was possible to misread The Bob Show as less than an act. Some viewers, tuning in after another day’s toil for a wild and woolly England side, may have found him unimpressed, perhaps even a little disillusioned, by the state of the game that confronted him. They just weren’t watching closely enough. The glint never lost the eye. The corners of the mouth always twitched upwards, even as daggers spat from it.

Bob Willis blew Australia apart at Headingley in 1981

Bob Willis blew Australia apart at Headingley in 1981

He was, and remained throughout his life, even on those grim days when England had been castled in a session on a featherbed, an advocate of cricket’s essential wonderfulness. Perhaps, now you listen back, it was true especially on those days.

It was inevitable that Sky would eventually ham up the persona, casting him as the modern game’s gavel-bashing overlord. But it never came at the expense of the work. He was always required listening, and never less than fair. He just said things on air that others did in private.

I didn’t know him well, but every time I met him was a good time. I did a podcast with him once, talking through the Headingley thing. That was mildly surreal. He was always gracious and even-handed. There was never any sense of a hierarchy at play, which can’t be said for all the others from his era.

And I was once involved in a magazine that he’d somehow been persuaded to contribute to as its ‘rock critic’. The gig involved him posing for photos dressed in leathers and drainpipes while channelling London Calling-era Paul Simonon.

I knew then, watching all that nonsense take place, that Bob Willis was unquestionably and indubitably one of the good guys.