In an extraordinarily powerful piece in the 2018 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Tanya Aldred argued that cricket has a long way to go to rid itself of sexism.

Cricket’s first global event: the 1973 women’s World Cup. The first player to score a double-century in a one-day international: Belinda Clark. The first player to take ten wickets and score a century in the same Test: Betty Wilson. Don’t blush, baby. For over 200 years, cricket has had an unapologetically male gaze. Its public face – players, umpires, scorers, writers, photographers, advertisers, commentators, cameramen, producers – has been almost exclusively male, and its product has been tailored for a male audience.

So when Chris Gayle made a pass at journalist Mel McLaughlin on live television in January 2016, he felt safe. When the commentators in the studio snorted with laughter, and when Ten Sport’s Twitter account chuckled “#smooth”, they felt safe. It was fine to judge McLaughlin on how she looked, to humiliate her in her place of work. Why? Because it was banter. It was the way the world worked.

Then something happened. The public didn’t like Gayle’s behaviour. Commentators backtracked furiously. Andrew Flintoff, Chris Rogers and Ian Chappell all criticised him. He was fined $A10,000 by Melbourne Renegades, his franchise, and reprimanded by Cricket Australia. “Those sorts of comments border on harassment,” said James Sutherland, CA’s chief executive, “and are completely inappropriate in cricket.”

Did England’s 2017 Women’s World Cup win mark the start of a new era for the game in this country?

Did England’s 2017 Women’s World Cup win mark the start of a new era for the game in this country?

Gayle has not found another Big Bash franchise since – but he has played in the Indian Premier League, the Bangladesh Premier League, the Pakistan Super League and for Somerset in the Vitality T20 Blast. Indian condom company Skore thought it was a good idea to make an advertisement referencing the McLaughlin incident. And yes, there were still people who believed his behaviour was OK, even when a young woman had been harassed in plain sight.

The world has turned, but there are many revolutions to go. Records of women playing cricket go back to the 18th century. Matches between married women and their single sisters were popular spectacles, often attracting large bets,though regarded by many as grotesque.

In 1890, a crowd of 15,000 turned up in Liverpool to watch the Original English Lady Cricketers, the first professional women’s side. They were forced to disband after their (male) manager ran off with the money. But cricket grounds remained bastions of male privilege. On April 11, 1913, the suffragettes burned down the pavilion at The Nevill ground in Tunbridge Wells, part of a year’s campaign against sporting institutions, best remembered because Emily Wilding Davison threw herself to her death in front of King George V’s horse at the Derby.

But why The Nevill? One story has a Kent official saying: “It is not true that women are banned from the pavilion. Who do you think makes the teas?” The people of Tunbridge Wells were pleasingly disgusted, and the pavilion was rebuilt.

There was, though, some male support for the movement within sport, and playwright Laurence Housman claimed Jack Hobbs “startled the clubs of Piccadilly” by walking in the male section of a suffragette march. Two years before the introduction of universal suffrage in 1928, the Women’s Cricket Association were set up, and by 1930 the Women’s Cricket magazine was being published under the editorship of Marjorie Pollard, a WCA founder member, who later had a column in The Cricketer.

England women embarked on their first Test tour, of Australia, in late 1934, and returned home broke after funding the trip themselves. Wisden chose not to report the tour until 1938. Six decades later, the Almanack moved the venue for its annual dinner from the East India Club in St James’s Square after the editor’s wife was refused a drink at the bar.

Women continued to play the game they loved but, for the international cricketers among them, there were choices with consequences. Betty Wilson, who won 11 Test caps for Australia between 1948 and 1958 – averaging 57 with the bat and 11 with the ball – chose cricket over marriage and children. Everyone had to take unpaid leave to play, and the women were stuck on a merry-go-round of fund-raising for flights and kit.

Enid Bakewell, one of England’s finest, used to sell chocolate on the boundary at Trent Bridge to raise a few pennies. Women’s games were tolerated, but not taken seriously by the wider public, the media, or the authorities. Len Hutton was not alone when he harrumphed: “Ladies playing cricket – absurd. Just like a man trying to knit.”

Socially and economically disenfranchised, female cricketers had little power. Between the wars, cricket-watching had been popular with both sexes, but their experiences were very different. In 1930, Lancashire had 1,387 female members and 4,055 male, but women could neither become full members nor enter the pavilion. At Yorkshire, a woman could sit in the pavilion, but not become a full member with voting rights. At Lord’s, things had even further to go. In 1929, the WCA wrote to MCC to ask if they would stage a women’s match. The answer was an incredulous “no”.

In 1948, the WCA tried again. The reply read: “The chances of being able to fit in a game for the Association are so remote that it would be best to abandon the idea at once.” The Association persisted. MCC again said no in 1973, this time to hosting the deciding match in the first World Cup.

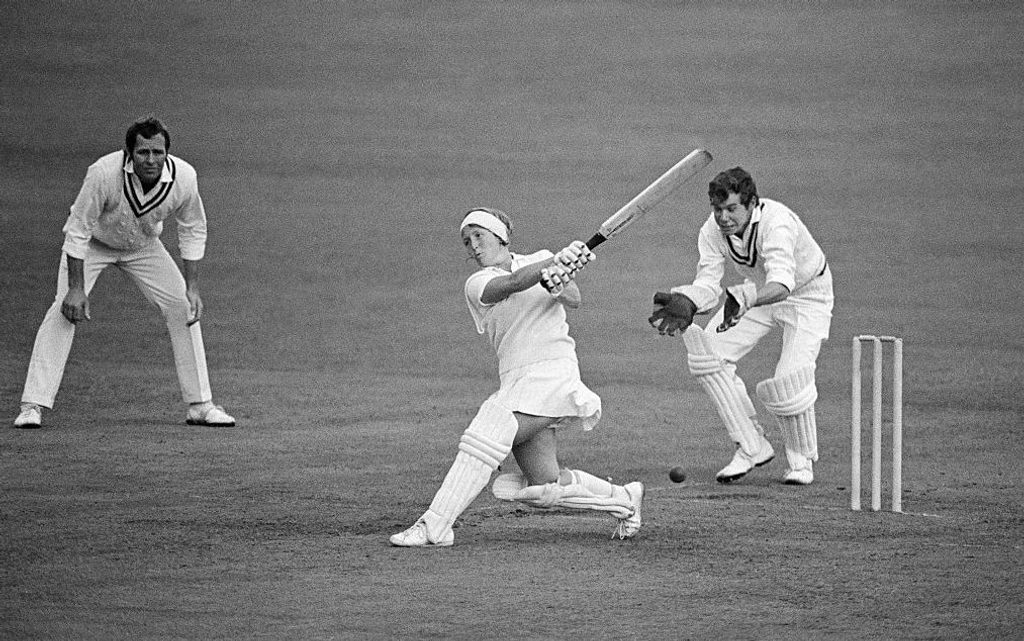

But in 1976, after intense lobbying from Rachael Heyhoe Flint, they relented, and agreed to a one-day game between England and Australia – provided Middlesex did not reach the quarter-finals of the Gillette Cup. They did not but, as a joyful Heyhoe Flint led her team on to the field, single women still needed a chaperone to get into the Warner and Tavern Stands. It would be two decades before women – typists, barmaids and the Queen excepted – would be let into the Pavilion.

Rachael Heyhoe-Flint was influential in the decision to stage an England vs Australia women’s ODI match in 1976

Rachael Heyhoe-Flint was influential in the decision to stage an England vs Australia women’s ODI match in 1976

That bastion fell in 1998, after club president Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie forced through two votes on women membership in seven months, and Wisden Cricket Monthly persuaded Isabelle Duncan, a Surrey club cricketer, to wear an MCC sweater on their front cover. Men voted against the motion for a variety of reasons: from not wanting to see “knitting needles in the Pavilion” to the worry of finding lacy lingerie in egg-and-bacon colours in the MCC shop; from the possibility of breastfeeding in the Long Room, to the social confusion that would occur if a man reserved his spot with a copy of The Daily Telegraph, yet had been raised to give his seat to a lady.

Eventually the sands of time caught up with even the Pavilion doorman – that, and the threat of missing out on Lottery money. Since then, MCC have been transformed – Duncan herself now sits on the general committee – though the number of women members remains small, and there is still no female statue to compete with the bronze WG in the Coronation Gardens. In fact, there is no well-known statue of a female cricketer anywhere.

In 1998, the WCA were subsumed into the newly formed ECB, a move that would be copied around the cricketing world, and an era came to an end. The women’s game would benefit hugely from more funding and greater professionalisation. However, as journalist Raf Nicholson has pointed out, the merger also meant that a women’s sport run by women was now a women’s sport run by men – with mainly male umpires and male coaches. The women who used to volunteer quietly vanished. A women’s cricket seat on the ECB board, requested by the disbanded WCA, was granted only in 2010. But with that loss of identity came something precious: money. And with money, at last, came opportunity.

The ECB, together with Chance to Shine, produced the first (semi-professional) contracts for women in 2008; full professionalisation came in 2014. Other countries followed, though with vastly different pay schemes for men and women. Then, in August 2017, after prolonged wrangling, Cricket Australia announced a new pay deal, christened the biggest windfall in women’s sport. A new memorandum of understanding covered men and women in the same agreement for the first time, with players earning the same hourly rate of pay. “This agreement is a huge step for sport in Australia,” said their former captain Jodie Fields, “because for the first time it considers male and female players as one entity.”

The ground was shifting. In fact, since 2015 women’s cricket in Australia has moved from being almost invisible unless you were a committed fan – the Women’s Big Bash League didn’t even have a marketing budget in its first year – to attracting impressive crowds. The opening weekend of the tournament’s third edition, last December, produced viewing figures far in excess of the second. CA aim to sell out a major stadium for the final of the women’s World T20, to be held on International Women’s Day 2020. And the commercial case continues to grow. “The 2017 World Cup built a bigger and stronger business case for the women’s game,” said Clare Connor, England’s director of women’s cricket. “There has to be a correlation between what has happened here and investment. We know it isn’t a saturated market.”

The Women’s Big Bash League has proven to be a major success

The Women’s Big Bash League has proven to be a major success

At administrative level, too, things are changing: the new ECB independent board has to be at least 30% female, and in Australia the target is 40% by 2022. In India, the BCCI have largely ignored women’s cricket, despite the huge commercial potential – though the 2017 World Cup may be a tipping point. Diana Edulji, a former player and now part of the Supreme Court appointed Committee of Administrators managing the affairs of the BCCI, has called the Indian board “a very male chauvinist organisation”.

She quoted their former president N. Srinivasan as saying, “If I had my way I wouldn’t let women’s cricket happen.” In February 2018, it was announced that Indra Nooyi, chairman and CEO of PepsiCo, would be appointed as an independent director. But until she takes her place in June, there will be no woman on the main ICC board.

There has also been a small but significant shift in the use of language: we now have the “Australian men’s team” and the “Australian women’s team”, not “Australia” and “Australia women”. It is the same for England and West Indies, while New Zealand’s men are the Black Caps and their women the White Ferns. In Australia, the Belinda Clark Award was redesigned as a medallion to match the Allan Border Medal. Just as symbolic was the decision to fly women cricketers business-class to the 2017 World Cup; for the World T20 the previous year in India, they had flown economy, unlike their male counterparts.

Historically, it has been difficult to know where sexism ended and homophobia began. But attitudes to homosexuality have changed rapidly over the last decade, and six of the countries that have played women’s Test cricket have now legalised gay marriage. Even so, Australia’s Alex Blackwell has spoken about the unhelpful assumption that male athletes are straight, female athletes gay.

“Sports have tended to focus on feminine attributes when promoting their female teams, perhaps to compensate for this public perception,” she said. But she was pleased that, at the 2016 Allan Border Medal night, she and her wife, the former England international Lynsey Askew, “were correctly referred to as a married couple. Having Cricket Australia proudly show us as a couple in a photo on their website made me feel included, and is a small but strong example of action being taken to become a more LGBTI-inclusive sport.”

But if there has been a revolution at the top, sex still sells. As recently as 2013, Neeraj Vyas, the business head of the Sony Max network in India, explained away the rolling cast of models he employed on his cricket show by saying they must be “younger and fresher” each year.

The IPL persists with its lavish use of mostly eastern European cheerleaders. And in October last year, after the Indian women’s captain Mithali Raj appeared on the cover of Vogue India, the ICC posted a tweet drawing attention to her looks. It was quickly deleted. Such a view of women is not merely unfunny: it becomes insidious.

Sexual harassment exists within cricket as it does in life – perhaps more so, given the sport’s male domination. A number of women working in the game have experienced inappropriate behaviour. Sleazy emails. Revolting comments. Rape jokes. Accusations of sleeping with the boss to get a job. Bottom pinching. Professional interviews that become awkward when a player chances his arm. A young Indian television reporter was asked by a prospective employer if she was prepared to have a boob job.

Twenty years ago, I was casually groped by an international cricketer. It would be nice to think things have changed, but still certain men are excused – because of their power, always their power. Most of the time, women let it lie because they are young or scared or unsure of their rights, or worried about jeopardising their reputations. Sometimes, they find the courage to speak out. Recently, one male journalist was sacked for inappropriate conduct with female workmates.

Women working in the game still experience sexual harassment

Women working in the game still experience sexual harassment

Another was reported to CA for assaulting a female colleague in the press box. He was accredited for the following home season, and when the two worked at the same match, CA seated the perpetrator in the main press box, and the woman in the secondary, overflow area. Asked for comment, CA said the matter was confidential.

“The incident was horrible and humiliating and unexpected in the press box, because the other journalists are incredibly respectful,” said the woman involved. “When females come in, we want to be part of the gang, valued for what we do. We don’t want special treatment, or to have anyone fight our battles for us. Privately, I had a lot of support, but publicly everyone carried on as if nothing had happened, because generally people don’t like confrontation or awkward situations, which I completely understand.

“At the same time it would have meant a lot to me had any of my colleagues told him what he did was disgusting and unacceptable, refused his invitations to events because of it, rather than accept them or make polite excuses. But I didn’t see anyone do that. If he’d done the same thing to their partners or daughters, I can’t help thinking social awkwardness wouldn’t have stopped them. It’s hard not to feel less valued by that thought. The only way things will really change is when the perpetrators feel they’re the ones who are not accepted.”

The point is a serious one. In 2013, five women accused two officials at the Multan Cricket Club in Pakistan of sexual harassment. At the PCB enquiry, three changed their statements, and the two others didn’t appear, amid speculation they had been pressurised into standing down. Club chairman Maulvi Sultan Alama brought a defamation case against the players. After the case collapsed, all five were banned for six months. One of them, Haleema Rafique, 17, later took her own life.

On social media, female writers come in for particularly vicious attacks. Lizzy Ammon of The Times says she gets sexist abuse four or five times a week. “It can batter you down: you ugly old hag, you deserve to be raped, she’s too ugly to be raped – there’s no way that doesn’t seep through.”

Cricket is not alone. Another woman who worked in a different sport spoke of the existence of “wank tapes” – slow-motion video footage of cheerleaders, close-ups of tits and arse, specially edited by men who worked on the programme, and played in the outside broadcast truck. Revolting. Depressing. Criminal.

That must mean dismantling barriers wherever they exist. So, stop judging women on how they look. Ensure women working in a cricket environment – from the television presenters to the cleaners – are treated as equals. Call it what it is if you see harassment. Educate the male players, teach young men about consent. Give a woman the first question in a press conference – it makes a difference.

Stop television’s cringe-making lascivious lingering over attractive women in the crowd. Use the correct language – Ireland’s Test against Pakistan in May will be the country’s first men’s Test: Ireland’s women played a Test 18 years ago.

Get rid of those cheerleaders from the IPL, or use an equal number of male dancers. Treat women’s cricket with respect. Cover it. Fund it. Value it. Enjoy it for what it is, rather than resent it for what it isn’t. Stop the constant comparisons with the men’s game. Cricket has continually evolved, shaken off the past and tried innovation on for size. Sexism has no place here anymore – by kicking it out, there is everything to be gained.