Walter Hammond, perhaps England’s greatest batsman, died aged just 62 on July 1, 1965. Fittingly, his Wisden obituary was written by one of the giants of cricket writing.

Read more Almanack tributes

Previous Almanack tribute: Fred Trueman: English cricket’s most enduring & best-loved character

When the news came in early July of the death of W. R. Hammond, cricketers everywhere mourned a loss and adornment to the game. He had just passed his 62nd birthday and had not played in the public eye for nearly a couple of decades, yet with his end a light and a glow on cricket seemed to go out. Boys who had never seen him said, “Poor Wally”; they had heard of his prowess and personality and, for once in a while, youth of the present was not sceptical of the doings of a past master.

“Wally” indeed was cricket in excelsis. You had merely to see him walk from the pavilion on the way to the wicket to bat, a blue handkerchief peeping out of his right hip pocket. Square of shoulder, arms of obvious strength, a beautifully balanced physique, though often he looked so weighty that his sudden agility in the slips always stirred onlookers and the batsmen to surprise.

At Lord’s in 1938, England won the toss versus Australia. In next to no time the fierce fast bowling of McCormick overwhelmed Hutton, Barnett and Edrich for 31. Then we saw the most memorable of all Wally’s walks from the pavilion to the crease, a calm unhurried progress, with his jaw so firmly set that somebody in the Long Room whispered, “My God, he’s going to score a century.”

Hammond at once took royal charge of McCormick, bouncers and all. He hammered the fast attack at will. One cover drive, off the backfoot, hit the palings under the Grandstand so powerfully that the ball rebounded half-way back. His punches, levered by the right forearm, were strong, leonine and irresistible, yet there was no palpable effort, no undignified outbursts of violence. It was a majestic innings, all the red-carpeted way to 240 in six hours, punctuated by 32 fours.

I saw much of Hammond in England and in Australia, playing for Gloucestershire on quiet West Country afternoons at Bristol, or in front of a roaring multitude at Sydney. He was always the same; composed, self-contained, sometimes as though withdrawn to some communion within himself. He could be changeable of mood as a man; as a cricketer he was seldom disturbed from his balance of skill and poise. His cricket was, I think, his only way of self-realisation. On the field of play he became a free agent, trusting fully to his rare talents.

His punches, levered by the right forearm, were strong, leonine and irresistible

His punches, levered by the right forearm, were strong, leonine and irresistible

His career as a batsman can be divided into two contrasted periods. To begin with, when he was in his 20s, he was an audacious strokeplayer, as daring and unorthodox as Trumper or Compton. Round about 1924 I recommended Hammond to an England selector as a likely investment. “Too much of a ‘dasher’”, was the reply. In May 1927, in his 24th year, Hammond descended with the Gloucestershire XI on Old Trafford. At close of play on the second day Lancashire were so cocksure of a victory early tomorrow (Whit Friday) that the Lancashire bowlers Macdonald, Richard Tyldesley and company, arranged for taxis to be in readiness to take them to the Manchester races.

Macdonald opened his attack at half-past eleven in glorious sunshine. He bowled his fastest, eager to be quick on the spot at Castle Irwell to get a good price on a “certainty”. Hammond, not out overnight, actually drove the first five balls, sent at him from Macdonald’s superbly rhythmical arm, to the boundary. The sixth, also, would have counted – but it was stopped by a fieldsman sent out to defend the edge of the field, in front of the sight-screen straight deep for the greatest fast bowler of the period, bowling his first over of the day and in a desperate hurry to get to the course before the odds shortened.

That day Hammond scored 187 in three hours – four sixes, 24 fours. He hooked Macdonald mercilessly, yes, Wally hooked during the first careless raptures of his youth.

Hammond succeeded Hobbs as England’s batting rock

Hammond succeeded Hobbs as England’s batting rock

As the years went by, he became the successor to Hobbs as the Monument and Foundation of an England innings. Under the leadership of D. R. Jardine he put romance behind him “for the cause”, to bring into force the Jardinian theory of the Survival of the Most Durable.

At Sydney, he wore down the Australians with 251 in seven and a half hours (on the 1928/29 tour); then, at Melbourne, he disciplined himself to the extent of six and three-quarter hours for 200, with only 17 fours: and then, at Adelaide, his contributions with the bat were 119 (four and a half hours) and 177 (seven hours, 20 minutes). True, the exuberant Percy Chapman was Wally’s captain in this rubber, but Jardine was the Grey Eminence with his plotting already spinning fatefully for Australia’s not distant future. In five Tests of this 1928/29 rubber, Hammond scored 905 runs at an average of 113.12.

***

Walter Reginald Hammond was born in Kent at Dover on June 19, 1903, the son of a soldier who became Major William Walter Hammond, Royal Artillery, and was killed in action in the First World War. As an infant, Walter accompanied the regiment with his parents to China and Malta. To the bad luck of Kent cricket when he was brought back to England he went to Portsmouth Grammar School in 1916 and two years later moved with his family to Cirencester Grammar School, rooting himself for such a flowering as Gloucestershire cricket had not known since the advent of W.G. Grace.

In all first-class games, Hammond scored 50,493 runs, average 56.10, with 167 centuries. Also he took 732 wickets average 30.58. In Test matches his batting produced 7,249 runs, average 58.45.

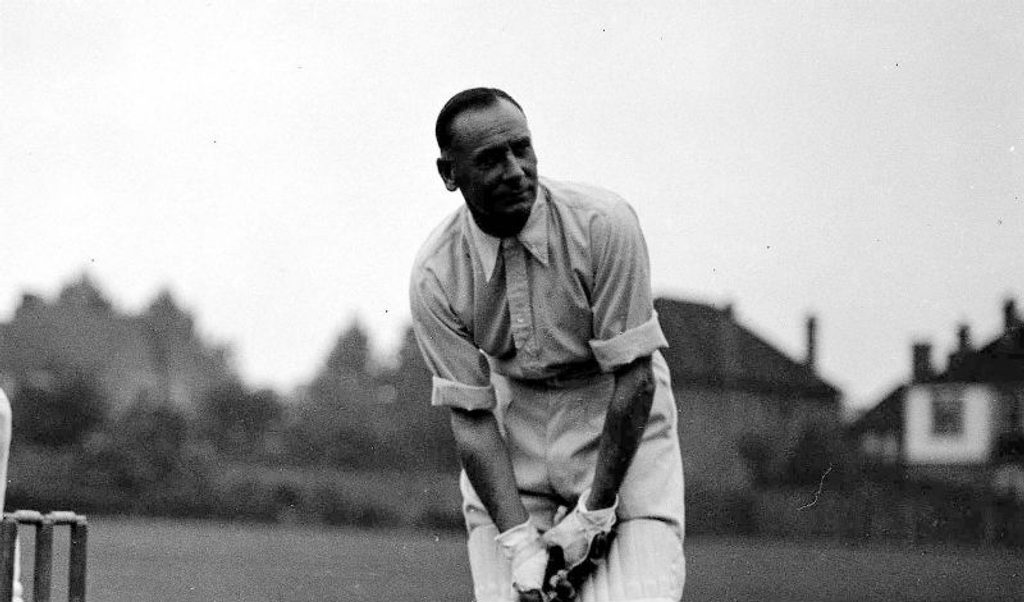

Wally Hammond taking a catch in the slip cordon

Wally Hammond taking a catch in the slip cordon

As a slip fieldsman his easy, lithe omnipresence has not often been equalled. He held 78 catches in a single season, ten in one and the same match. He would stand at first slip erect as the bowler began to run, his legs slightly turned in at the knees. He gave the impression of relaxed carelessness. At the first sight, or hint of, a snick off the edge, his energy swiftly concentrated in him, apparently electrifying every nerve and muscle in him. He became light, boneless, airborne. He would take a catch as the ball was travelling away from him, leaping to it as gracefully as a trapeze artist to the flying trapeze.

Illness contracted in the West Indies not only kept him out of cricket in 1926; his young life was almost despaired of. His return to health a year later was a glorious renewal. He scored a thousand runs in May 1927, the season of his marvellous innings against Macdonald at Whitsuntide at Old Trafford.

I am gratified that after watching this innings I wrote of him in this language: “The possibilities of this boy Hammond are beyond the scope of estimation; I tremble to think of the grandeur he will spread over our cricket fields when he has arrived at maturity. He is, in his own way, another Trumper in the making.”

Some three years before he thrilled us by this Old Trafford innings he astounded Middlesex, and everybody else on the scene, by batsmanship of genius on a terrible wicket at Bristol. Gloucestershire, in first, were bundled out for 31. Middlesex then could edge and snick only 74. In Gloucestershire’s second innings Hammond drove, cut and hooked no fewer than 174 not out in four hours winning the match. By footwork he compelled the bowlers to pitch short, whereupon he massacred them. He was now hardly past his 20th year.

Like Hobbs, he modulated, as he grew older and had to take on heavier responsibilities as a batsman, into a classic firmness and restraint. He became a classical player, in fact, expressing in a long innings the philosophy of “ripeness is all”. It is often forgotten that, on a bad wicket, he was also masterful. At Melbourne, in January 1937, against Australia, on the worst wicket I have ever seen, he scored 32 without once losing his poise though the ball rose head-high, or shot like a stone thrown over ice.

Wally Hammond was also handy with ball in hand

Wally Hammond was also handy with ball in hand

He could, if he had given his mind constantly to the job, have developed into a bowler as clever as Alec Bedser himself with a new ball. Here, again, he was in action the embodiment of easy flowing motion – a short run, upright and loose, a sideway action, left-shoulder pointing down the wicket, the length accurate, the ball sometimes swinging away late. I never saw him besmirching his immaculate flannels by rubbing the ball on his person, rendering it bloody and hideous to see.

He was at all times a cricketer of taste and breeding. But he wouldn’t suffer boredom gladly. One day at Bristol, when Lancashire were scoring slowly, on deliberate principle, he bowled an over of ironic “grubs”, all along the ground, underhand.

As a batsman, he experienced only two major frustrations. O’Reilly put him in durance by pitching the ball on his leg-stump. Wally didn’t like it. His batting, in these circumstances, became sullen, a slow but combustible slow fire, ready to blaze and devour – as it did at Sydney, in the second Test match of the 1936/37 rubber. For a long time Hammond couldn’t assert mastery over O’Reilly. For once in his lifetime he was obliged to labour enslaved. In the end he broke free from sweaty durance, amassing 231 not out, an innings majestic, even when it was stationary. We could always hear the superb engine throbbing.

The other frustration forced upon Wally occurred during this same 1936/37 rubber. At Adelaide, when victory at the day’s outset – and the rubber – was in England’s reach at the closing day’s beginning, Fleetwood-Smith clean bowled him. Another of Wally’s frustrations – perhaps the bitterest to bear – befell him as England’s captain. At a time of some strain in his life, he had to lead in Australia, in 1946/47, a team not at all ready for Test matches, after the long empty years of world war. Severe lumbago added to Hammond’s unhappy decline.

Those cricketers and lovers of the game who saw him towards the end of his career saw only half of him. Nonetheless they saw enough to remain and be cherished in memory. The wings might seem clipped, but they were wings royally in repose.

Wally had a quite pretty chassé as he went forward to drive; and, at the moment his bat made impact with the ball his head was over it, the Master surveying his own work, with time to spare. First he played the game as a professional, then turned amateur. At no time did he ever suggest that he was, as Harris of Nottinghamshire called his paid colleagues, “a fellow worker”. Wally could have batted with any Prince of the Golden Age at the other end of the pitch – MacLaren, Trumper, Hobbs, Spooner, Ranji – and there would have been no paling of his presence, by comparison.