One of England’s greatest all-rounders, Trevor Bailey, died in February 2011. His Wisden Almanack obituary reappraised his career.

Bailey, Trevor Howard, CBE, died in a house fire on February 10, 2011, aged 87

Trevor Bailey may have been the least glamorous of the names sprinkled through one of England’s finest teams. He was not blessed with the stately elegance of May or Cowdrey, nor the fast–bowling fury of Trueman. He did not enjoy the profound affection inspired by Hutton, nor write his name into history with one performance, like Laker. And he certainly lacked the matinee-idol flamboyance of Compton. Yet he was never less than an essential component of the side that was the best in the world for much of the 1950s, especially during their rare crises.

There were not many of his 61 Tests between 1949 and 1959 when he was not, as Wisden put it, “doing something useful”. A final analysis of 132 wickets at 29.21 and 2,290 runs at 29.74 was just that.

Bailey’s Test career lasted from 1949 to 1959

Bailey’s Test career lasted from 1949 to 1959

Yet Bailey remained a controversial figure, and there were regular debates about the speed of his scoring, his unswerving commitment to victory – or perhaps to avoiding defeat – and his undisguised fondness for a commercial opportunity, despite the retention of his amateur status. Beyond doubt, however, was that he was an all-rounder who used every ounce of his talent and possessed a shrewd cricket brain. His batting traits – sleeves rolled up above the elbows, gloves tugged on with his teeth and, above all, the impassable forward defensive – became symbols almost of national security.

His service to Essex, where he spent his entire life, was remarkable. Between 1946 and 1967 he played in 482 first-class matches for them, was captain for six years and secretary for a dozen. After retirement, he immersed himself in a variety of roles, most famously as a summariser on Test Match Special. For more than 30 years, his penetrating analysis and crisp judgments became as synonymous with the programme as John Arlott’s lyricism and Brian Johnston’s levity.

Bailey’s renown as a player rests to a great extent on his feats against Australia, and especially on two performances in 1953, when England won the Ashes for the first time since Bodyline. On the final day of the Second Test at Lord’s, he and Willie Watson staged a celebrated rearguard. With England 20 for three overnight, the morning papers had already composed the death notices and were preparing the post-mortem. Bailey bridled at such presumption and, joining Watson at 12.42 pm, set out to provide his own headlines.

For more than four hours they repelled a potent Australian attack; when, at one point during their stand of 163, Watson suggested they might even have a go at the target of 343, Bailey simply turned his back and walked away. Watson went first, and Bailey’s anguish at his own dismissal for 71 after a careless drive is preserved on the Pathe’s News film footage. There were still some nervous moments, but England held on.

Bailey (top row, far left) played a key role in helping England to victory in the 1953 Ashes

Bailey (top row, far left) played a key role in helping England to victory in the 1953 Ashes

The series stalemate was preserved at Old Trafford but, on the final day of the Fourth Test at Headingley, Bailey was pragmatism personified. His defiance began with an innings of 38 in 262 minutes to extend England’s fragile lead and eat into the time for the run-chase. “Immovable and enigmatic as the sphinx,” reported The Times as he employed every possible device to slow the match down: as the clock ticked around to lunchtime he even appealed against the light while the sun shone. After the time it took umpires Frank Chester and Frank Lee to consult, it was too late for Ray Lindwall to begin an over to Jim Laker.

Australia still looked like achieving a target of 177 in 115 minutes, thanks to Len Hutton’s misplaced faith in his spinners. But Bailey replaced Laker and bowled six overs of calculated negativity down leg with a packed on-side field. He also extended his run-up and, recalled John Woodcock, “suddenly had a lot of problems with his bootlaces”.

Once again, a draw was salvaged, and the series headed for The Oval locked at 0–0. There, Bailey made 64 to give England a precious first-innings lead and, amid scenes of national rejoicing, the Ashes were at last theirs. Sid Barnes, the former Australian batsman, called him a “petulant schoolboy” for his unvarnished gamesmanship, but Bailey was unrepentant. “Headingley was the performance he was most proud of,” said his great friend and Essex team-mate Doug Insole. “If Australia had won there, they would have retained the Ashes.”

He was born into a comfortable middle-class household in Westcliff-on-Sea, a suburb of Southend, in 1923. His father was a civil servant at the Admiralty, and Trevor attended Alleyn Court prep school where he showed promise as a fast bowler and was taught to bat by the headmaster Denys Wilcox, who combined running the school with captaining Essex. At Dulwich College he made the first XI in his first year and, after the team won all their matches, old boy P. G. Wodehouse treated them to a night in the West End. If Wodehouse was impressed by the newcomer, he revised his opinion after watching him bat against St Paul’s in 1939. “Bailey awoke,” he wrote, “from an apparent coma to strike a boundary.”

Commissioned into the Royal Marines in the Second World War, Bailey remained deeply affected by the experience of driving past Belsen soon after the camp had been liberated. In 1946, he began his first-class career with Essex, opening the batting and bowling on his Championship debut against Derbyshire at Ilford; the following year he went up to St John’s College, Cambridge, where he read history and won Blues for cricket and football in both his years there. He also began an enduring friendship, forged over a common love of sport and Hollywood Westerns, with fellow undergraduate Insole.

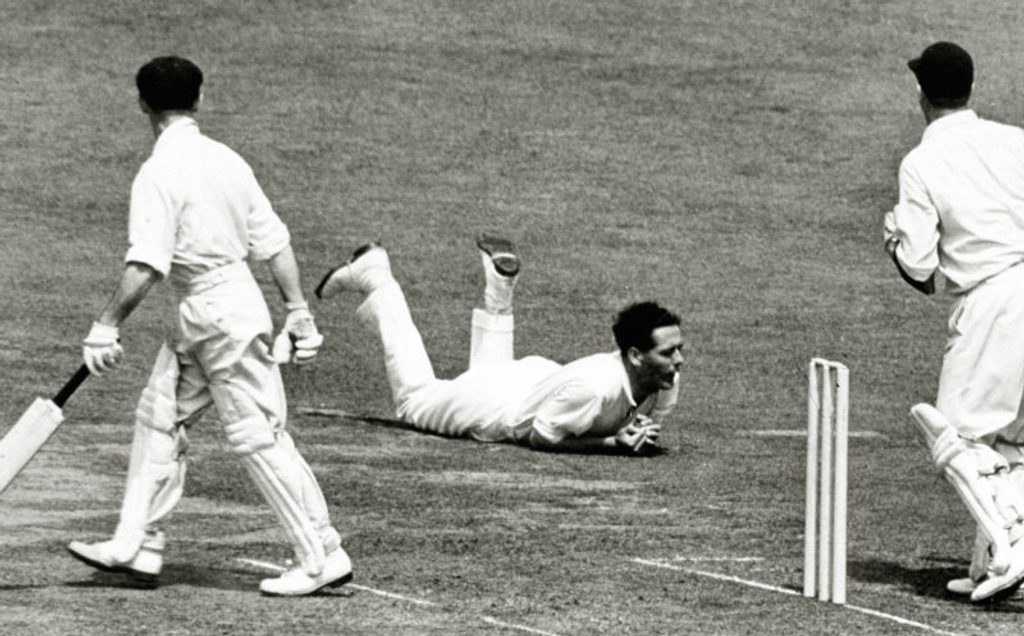

Bailey taking a catch in the 1953 Lord’s Test

Bailey taking a catch in the 1953 Lord’s Test

In the golden summer of 1947, Bailey made centuries for the university against Yorkshire and Gloucestershire, as well as taking 82 first-class wickets and hitting 205 – which would remain a career-best – for Essex against Sussex at Eastbourne, playing alongside Wilcox. But his education was furthered considerably in four encounters with Don Bradman’s Invincibles in 1948.

Bailey scored an undefeated 66 for Cambridge at Fenner’s but then, though not fully fit, agreed to play in the tourists’ next game, against Essex at Southend. He begged a lift on the Australians’ coach and had his first experience of the Anglo-Aussie cultural divide. “They were so far from the Cambridge and Essex players I knew that they almost seemed to have come from a different planet,” he recalled later. The next day he was part of an attack that yielded 721 runs. And when he came up against the Australians again, playing for the Gentlemen of England at Lord’s, and the South at Hastings, he conceded 112 in 27 overs and 125 in 21.

These experiences prompted an overhaul of his bowling. Realising he would never consistently reach express pace, he modified his action and run-up, and developed variations. Within a year he was opening the bowling for his country.

Bailey took the elevation to Test cricket in his stride and, in the four–match series against New Zealand in 1949, claimed 16 wickets, including six in the first innings of his debut at Headingley and another six-for at Old Trafford; he also scored 219 runs. Not long after, he took all ten against Lancashire at Clacton. He toured Australia in 1950-51, enhancing his reputation; soon after, in New Zealand, he made his only Test century, 134 not out at Christchurch.

His finest hour as a bowler came, more typically, under pressure – on the opening day of the final Test of the 1953-54 tour of the West Indies. Hutton’s team were trailing 2-1 and shorn of the services of Brian Statham, but Bailey bowled with sustained skill in fierce Jamaican heat to take seven for 34. Opening the batting with Hutton, he then survived until stumps. England won the match and squared the series.

It was a fractious trip and, as Hutton’s vice-captain, he may have shouldered some of the blame when enquiries were made at Lord’s. That, and his Headingley gamesmanship the previous summer, put paid to any captaincy ambitions. There were those who saw echoes of Douglas Jardine in his ferocious determination, and an untimely newspaper serialisation of his book, Playing to Win, did not help; nor, probably, did the title. But Bailey remained a key member of the team, not least on Hutton’s triumphant Ashes tour of 1954-55. It was, said Insole, in the wider interests of the side that he became an avowedly defensive batsman. “He decided his most useful role would be to prop things up,” he said. “It was not his natural game. He also found it very difficult to play at two paces in one innings.”

He made a third trip to Australia in 1958-59, but it was an unhappy one. He cemented his reputation for dourness in the second innings at Brisbane with an excruciating 68 in seven and a half hours. The Australian public – watching the country’s first televised Test – must have realised why their team had long dubbed him “barnacle” or “barn door”. His Test career ended on a pair inflicted, with grim irony, by Lindwall at Melbourne: four years earlier, Bailey had generously – some might say uncharacteristically – allowed Lindwall, on 99 Ashes wickets with the declaration due, to bowl him.

Just in case the selectors were having second thoughts, he did the double of 2,000 first-class runs and 100 wickets in 1959 – a unique feat in post–war cricket. He achieved 1,000 runs and 100 wickets eight times, but one of his most significant acts for Essex was to secure an interest- free loan from Warwickshire to build a permanent ground at Chelmsford. The seeds of the county’s later success were sown.

Bailey also played football for Walthamstow Avenue and Leytonstone, and in 1952 was in the Walthamstow team that won the FA Amateur Cup at a packed Wembley. A year later, the team reached the fourth round of the FA Cup, and drew 1–1 with Manchester United at Old Trafford before succumbing 5–2 in the replay at Highbury. It was East End football supporters shouting “Come on, Boiley” who were said to have bestowed his most enduring nickname, “the Boil”.

He advertised Brylcreem, Lucozade and Shredded Wheat, and claimed to be the first cricketer to have a sponsored car. At Brisbane on the 1954–55 tour he made sure he claimed the £100 offered by a local businessman for the first six of the match. “He can hardly have envisaged Bailey as the recipient,” wrote Alan Ross. His hotel bedroom was referred to as “the office” as he worked on his latest newspaper article. He gave a lasting legacy to cricket historians with the cine films he took on tour, and went on to become cricket and football correspondent of the Financial Times.

Bailey went on to become a key part of the TMS team. Pictured from left to right – Brian Johnstone, Bailey, Don Mosey and Henry Blofeld

Bailey went on to become a key part of the TMS team. Pictured from left to right – Brian Johnstone, Bailey, Don Mosey and Henry Blofeld

Bailey made his first appearance on TMS in 1967 and gradually became a regular summariser. “It was Trevor who had the idea for Call the Commentators,” said former producer Peter Baxter. “Initially, it was called Cricket Clinic and was answering technical questions from club players. That arose from the amount of mail Trevor received with such questions.”

He became known for his short sharp summaries. In Madras in 1992-93, Jonathan Agnew asked him for his thoughts on the trio of spinners who had been responsible for England’s downfall in the previous match. Bailey had not seen that game so Agnew helpfully handed him the bowling figures. Undeterred by not having his glasses, and barely able to read the names of Venkatapathy Raju, Anil Kumble and Rajesh Chauhan, he barked: “Ragi: ordinary. Kimble: good bowler. Shoosson: chucker.”

In 1999 his and Fred Trueman’s TMS contracts were not renewed. The BBC suddenly faced competition from commercial radio, and it was not until changes had been promised in the commentary box that the BBC’s exclusive deal to cover England Tests was confirmed. “Trevor said the thing that disappointed him most was that he was not able to say goodbye to the listeners,” Baxter said.

To mark his 80th birthday, the Cricketers Club of London had to hold three lunches to accommodate all those who wanted to pay tribute. The manner of his passing, in an early-morning fire at the flat he shared with Greta, his wife of 62 years, added to the dismay of friends and admirers. There were many tributes, but perhaps his best epitaph had been written, years before, by Trueman. “That man,” he said, “was such a fighter he should have been a Yorkshireman.”