Tony Greig, who died on December 29 in 2012, was one of the most influential figures in the development of the modern game. His Wisden obituary put his career into perspective.

Grieg, Anthony William, died on December 29, 2012, aged 66.

For a brief few years in the mid–1970s, Tony Greig was arguably the leading all-rounder in Test cricket – a belligerent middle-order batsman capable of match-turning hundreds, a wicket-taking bowler (in two styles) who bristled with attacking intent, and a magnificent fielder in any position. By 1975, he was pouring those attributes into gung-ho leadership of England. Throw in his iridescent stage-presence, and it is easy to see why he was talked of as cricket’s first superstar.

English cricket’s showman of the 1970s

English cricket’s showman of the 1970s

Greig was born in Queenstown in the Eastern Cape to a Scottish father and South African mother. His was an archetypal white middle-class South African upbringing (although his parents were liberal in matters of race), and a young Greig barely paused for breath between games of cricket, tennis and rugby. At home he played cricket for hours with “Tackies”, the family gardener, who had an inexhaustible appetite for bowling. The only blot on a sunny landscape was epilepsy, first revealed when he collapsed playing tennis aged 14. In the main, Greig managed to control the illness for the rest of his life.

He attended the local Queen’s College, a favourite winter destination for Sussex cricketers, who returned to Hove with glowing reports. It was the influence of Mike Buss that secured a trial, and Greig set off for the south coast soon after his first-class debut for Border in February 1966, aged 19. Opportunities were rationed, but he made a century in each innings for Colonel L. C. Stevens’ XI against Cambridge University at Eastbourne, and took three West Indian wickets for A. E. R. Gilligan’s XI at Hastings. Sussex offered him a contract and, with some reluctance, his father heeded Greig’s pleas to put cricket before a place at a South African university. Permission came with a proviso: he had four years to reach the top. It was a mission that began spectacularly on his Championship debut, against Lancashire at Hove in May 1967. Coming to the wicket with Sussex 34 for three against an attack led by Brian Statham and Ken Higgs, he made 156, showing scant regard for the principles of early-season batting in England. Two months later, he took eight for 25 against Gloucestershire.

Greig (left) walking out to bat with Ted Dexter (right) for Sussex in 1967

Greig (left) walking out to bat with Ted Dexter (right) for Sussex in 1967

He passed 1,000 runs and 50 wickets in each of his first three seasons with Sussex and, if centuries and five-fors proved elusive, his true qualities transcended statistics – an unshakable confidence, a desire to attack in any situation, and a talent for inspiring those around him. At 6ft 7½in, and strikingly blond, he also exuded charisma. “He was just so different,” said team-mate Peter Graves. “He had that boyish exuberance. And he was noisy.”

By 1970, Greig had completed his residency and – while his former countrymen embarked on their 22-year exile – was selected for England against the Rest of the World at Trent Bridge. Characteristically undaunted, he took four for 59 on his first day in international cricket, then hit two of his first three balls for four. But he was less successful at Edgbaston and Headingley, and was dropped for the final match. His next career boost came from an unlikely source. Garry Sobers was leading a Rest of the World squad to Australia in 1971–72 and, when Mike Procter withdrew, he suggested to Don Bradman, overseeing the tour, that Greig should take his place. Arriving in Adelaide, Greig survived a mortifying moment when he palmed off his luggage on the bespectacled, cardigan- wearing figure who greeted him. Only later did he twig: the bagman was Bradman. But it was a successful trip. Greig played in all five of the unofficial Tests and, by the time the Australians arrived in England in 1972, the selectors gave him another chance.

Greig was a ray of light in the First Test at a gloomy Old Trafford, top–scoring twice, with 57 and 62, taking four wickets, and exciting Jack Fingleton: “Greig was an outstanding success, proving himself England’s best all-round gain in years.” Thereafter, his performances were less eye-catching, but further mature displays came that winter in India. At Delhi, he shared a Christmas Day stand of 101 with his captain Tony Lewis, helping England to victory; at Calcutta, he took his first Test five-wicket haul; at Bombay, he made his first century. “We sat down for a long chat over a glass of wine at the end of the tour,” Lewis said. “One thing we had in common was that we were both always looking ahead of the game, not back on it. We both believed in trusting your luck and obeying your gut instinct.”

So began the years of Greig’s pomp. From the trademark upturned collar, everything about him seemed designed to attract attention: at the crease, he held his bat high in defiance of the textbook (Bradman tut-tutted), and used his tremendous reach to get on the front foot as often as possible. His cover-driving of fast bowlers was a display of power and elegance. When bowling, his hectic approach was a mass of pumping legs and jutting elbows. In the field, he was seldom far from the action, staring batsmen down from close in, or grasping edges in the slips.

An all-round sensation

An all-round sensation

He was appointed vice–captain to Mike Denness for the tour of the West Indies in 1973– 74, but in the First Test in Trinidad, his combativeness backfired. Fielding the final ball of the second day at silly point, Greig spotted that Alvin Kallicharran, unbeaten on 142, had begun to walk off, and threw down the non-striker’s stumps. Having not yet called time, umpire Douglas Sang Hue had no option but to uphold the appeal. The England team left the field to a fusillade of boos, and things might have turned nasty had the scoreboard operators altered the number of wickets. Even so, the presence of angry supporters outside the ground persuaded Sobers to drive Greig back to the hotel. An evening of intense diplomatic activity ensued, ending with Kallicharran’s reinstatement. England issued a statement apologising for Greig’s “instinctive action”, and next morning he reluctantly agreed to shake Kallicharran’s hand.

When England returned to the Queen’s Park Oval for the final Test, still trailing 1-0, Greig produced perhaps his most unlikely match-winning performance, taking eight for 86 in West Indies’ first innings with brisk off-breaks. He had experimented with them in the Second Test in Jamaica, but purely as a defensive measure. Now, the extra bounce at Port-of-Spain made them a viable attacking weapon, and he added five for 70 in the second innings as England squared the series. Alan Knott called it the finest off-spin bowling he had kept to, but for Derek Underwood it paradoxically marked the end for Greig as an effective Test bowler: “At Trinidad he just hit the right rhythm and pace, but after that he never knew what to do, or what to bowl, on any particular day or wicket.”

Another thrilling performance followed later that year, this time with the bat, at Brisbane. Arriving at 57 for four, with Jeff Thomson and Dennis Lillee in full cry, Greig launched an extraordinary counter-attack, driving with savage intent and cutting anything short over the heads of an astonished slip cordon. He scored 110. “It was one of the best half-dozen innings I ever saw,” said John Woodcock. Greig’s relish for a battle was never more obvious than when he infuriated Lillee by treating bouncers with an exaggerated trembling of the knees, and signalling his own boundaries. His colleagues were impressed by his impudence but appalled by the likely consequences: “Think of the poor bastard at the other end,” Underwood told him. It is easy to imagine the television mogul Kerry Packer noting this bravura performance and luminous screen presence.

When England’s shell-shocked team quickly embarked on a home series with Ian Chappell’s bruisers, Denness was on borrowed time, and resigned halfway through the First Test. Greig’s captaincy credentials had been buffed by, among others, E. W. Swanton (an improbable, but staunch, supporter), Ian Wooldridge and Wisden, although Greig himself felt he had been offered the role only because there were no alternatives. Keen to add backbone to England’s fragile batting, he sought the opinion of umpires, who told him Northamptonshire’s No. 3, David Steele, was the man to stand up to Lillee and Thomson. It proved a shrewd move: in contrasting styles, Greig and Steele restored national pride on a sunlit first day at Lord’s. Greig made 96, Steele 50 and, though the match was drawn and Australia protected their 1–0 lead for the rest of the summer, there was a seismic shift in atmosphere. “He was such a great competitor,” said Steele.

Greig as England captain (bottom row, centre) in 1976

Greig as England captain (bottom row, centre) in 1976

With no England tour that winter, Greig accepted an offer to play grade cricket for Waverley in Sydney, where his on-field success became almost incidental to business contacts and promotional deals. Back in England, he gave an interview to the BBC’s Sportsnight programme ahead of the 1976 West Indies series. Irked by what he saw as the journalist’s emphasis on the qualities of the opposition, he retorted: “I’m not really sure they’re as good as everyone thinks they are.” Next came a comment destined for folklore: “If they get on top, they are magnificent cricketers. But if they are down, they grovel, and I intend – with the help of Closey and a few others – to make them grovel.” From any previous England captain, the remark might have been dismissed as crass psychology; from a white South African, it was just crass. The West Indians were furious. During a long, hot summer, England’s optimism of 1975 drained away in a 3-0 defeat, although Greig responded with a typically feisty century in the Fourth Test at Headingley, before finally grovelling himself, on hands and knees, in front of jubilant West Indian supporters at The Oval.

If Greig had learned something about public relations, he soon put it to good use in India. His charm offensive began before a ball was bowled, when he ostentatiously praised the local umpires. Ahead of one game, he made his men don blazers and jog around the outfield, waving to the crowd. If Greig was in the middle when a firecracker went off, he would fall to the ground as if he had been shot, and he encouraged Derek Randall to play to the gallery too. Thought was also given to the serious business of winning matches. Underwood recalled: “Before we left for India he said to me, ‘You are going to win us the series. If you don’t want to play in any of the games outside the Tests, just let me know and I’ll make sure you don’t have to.’ Nobody had spoken to me like that before.”

Greig’s leadership was inspirational, never more so than in the Second Test at Calcutta, where he batted for more than seven hours with a fever and in a state of near-exhaustion to score 103. It was his second truly great Test innings – and this time in a winning cause. The series was secured when England went 3–0 up at Madras, to complete Greig’s finest hour as captain. Before the party left India, Gubby Allen wondered aloud to friends: “Is he really too good to be true?”

An answer of sorts was around the corner. At the Centenary Test in Melbourne, Greig again showed slick PR skills with a letter to the Age newspaper, thanking the city for its hospitality. But he immediately boarded a flight to Sydney: Packer, owner of Channel Nine, wanted to see him. Infuriated with the Australian Cricket Board’s refusal to sell him the TV rights to Test cricket, Packer was plotting to set up his own breakaway series – and the telegenic Greig was vital to the plan.

Greig was offered $A90,000 for three years, with the guarantee of a job for life at the Packer organisation. He wanted time to think it over, but did not need long. Returning to London, he was ambushed by Eamonn Andrews for This is Your Life, but found time to make contact with Packer’s other English targets. Two days later, he flew to Trinidad to help recruit West Indians and Pakistanis playing a Test there. Packer’s heist remained secret for a few more weeks, long enough for the Australian touring party to arrive in England to defend the Ashes in 1977. Sussex players noted that the dressing-room attendant was suddenly taking a lot more calls for “Mr Greig”. Eventually, as the news leaked in Australia, Greig issued a statement on May 8, announcing a “massive cricket project” for the next Australian summer. He then headed for Hove, hit 50 from 36 balls against Yorkshire, and told Geoff Boycott in the car park to keep an eye on the morning papers.

Greig (bottom row, second from left) in his final Test match at the Oval in August 1977

Greig (bottom row, second from left) in his final Test match at the Oval in August 1977

Retribution was swift. By the end of the week he had been stripped of the England captaincy while, curiously perhaps, retaining his place in the team, now led by Mike Brearley. It was an odd summer. Against a distracted, divided Australian side, England won easily, with Greig making 91 at Lord’s and 76 at Old Trafford. Brearley was appreciative. “When he was dismissed as captain, he might have shown more resentment, or have been only moderately co–operative,” he wrote. “In fact, he could not have been more helpful.” Elsewhere, there were less kind words: he was, wrote Woodcock, not English “through and through”, and his cloak-and-dagger defection severed many alliances; Greig always regretted not being able to forewarn Alec Bedser, Ken Barrington and Swanton. County dressing-rooms containing Packer players could be chilly places, but Graves insisted there was no problem at Hove: “We wished him well because it was obviously his future.” Tony Lewis saw it differently, calling his behaviour a “betrayal”.

As far as his Test career was concerned, though, that was that. In 58 matches, he made 3,599 runs at 40, with eight hundreds, and took 141 wickets at 32, with six five-fors. Among men to have played at least 25 Tests, only Greig, Aubrey Faulkner and Jacques Kallis have averaged 40 or more with the bat and 33 or fewer with the ball. Overall, in 350 first–class matches, Greig scored 16,660 runs at 31, and took 856 wickets at under 29.

He had never disguised his intention to become “the first millionaire cricketer”. Catching the militant mood of the 1970s, he once stood up at a Professional Cricketers’ Association meeting and suggested a work-to-rule on Sundays. But it was Packer who provided his route to those riches, and the pair strode down the Strand shoulder to shoulder when the WSC players took the authorities to the High Court after they had been banned from the first–class game; the players won. Greig was also at the forefront of promoting WSC in Australia, to the extent that his role as World XI captain became almost secondary. His form was wretched, leading to Ian Chappell’s barb that the World XI was “the best bunch of cricketers I’ve seen – with one exception”. Underwood said: “Out there he was an administrator as well as a cricketer. If there was a problem, he had the job of sorting it out.”

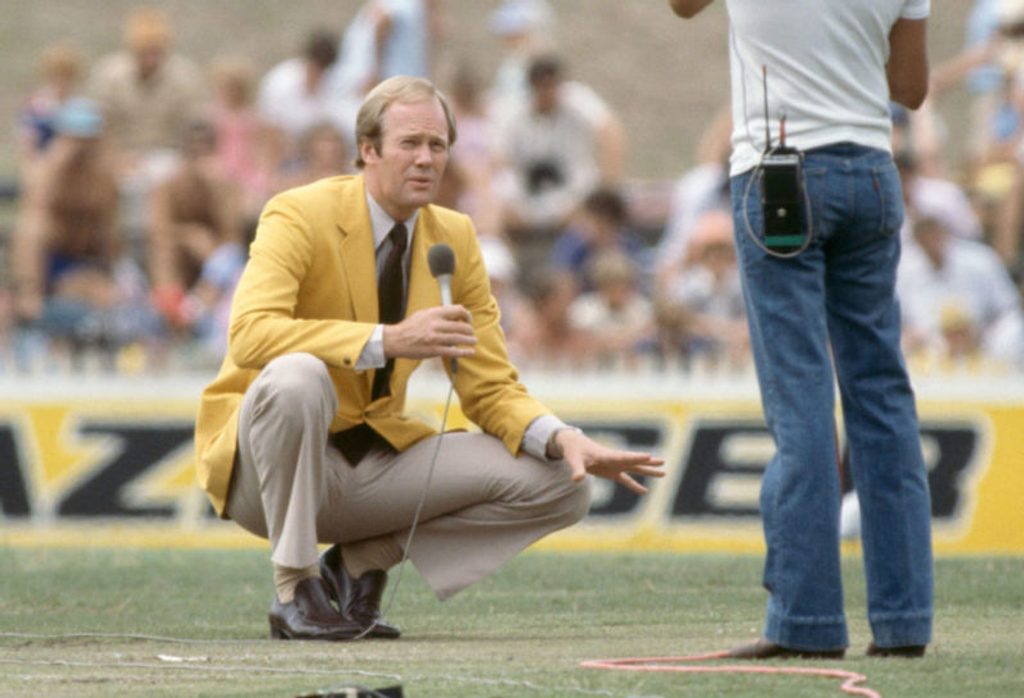

Greig as the beloved face of Channel Nine

Greig as the beloved face of Channel Nine

When a peace deal was brokered after two disrupted Australian summers, Packer’s offer of a job for life came good. For the next three decades, Greig was integral to Channel Nine’s coverage. His excitable style – “He’s gone, goodnight Charlie!” – did not please everyone, but his voice became almost as familiar as Richie Benaud’s, and his sparring with Bill Lawry was central to Australian humorist Billy Birmingham’s Twelfth Man parodies.

In the summer of 2012, Greig was invited by MCC president Phillip Hodson, his brother-in-law, to give the Spirit of Cricket Lecture. His first draft included no mention of the Packer years, until he was persuaded the topic could not be ignored, and he was typically outspoken on India’s role in the world game. In October 2012 it was revealed Greig was suffering from lung cancer; two months later, he died in a Sydney hospital after suffering a heart attack at home. On the Saturday morning when Britain awoke to the news, the honours list was published. Denness had been awarded an OBE. It left Greig as the only England captain without such recognition – an outsider to the end.