Four years ago, cricket was numbed by the tragic death of Australia batsman Phillip Hughes. The 2015 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack carried this magnificent tribute by Andrew Ramsey.

Andrew Ramsey is a senior writer for cricket.com.au

In Westleigh, a commuter suburb in the city where Phillip Hughes had once learned his trade, a simple gesture from a 48-year-old IT worker and former Sydney grade cricketer – who placed his bat outside his house, and a navy blue Mosman CC cap on the bat handle, and posted the photo on Twitter – lit the way for a global show of grief.

In Adelaide, Hughes’s adopted home, a 26-year-old nurse without the slightest interest in cricket sobbed uncontrollably when a radio bulletin confirmed the unspoken fear Australia had carried for two days.

The death of Hughes saw a whole country in mourning

The death of Hughes saw a whole country in mourning

In Macksville, the subtropical truck stop on the Pacific Highway that links Sydney and Brisbane, businesses closed their doors, and a community closed ranks around a grieving family.

Forty-eight hours earlier, when news spread that Hughes had been struck while batting in a Sheffield Shield match for his new state against his former team in his old home city, the initial reaction was that the blow might delay his return to the Test side. Even while the scroll of television-news tickertape was being punctuated with “induced coma” and “intensive care unit” – usually the vocabulary of road accidents, or acts of evil – it remained the consensus among those searching for reassurance.

But those at the SCG when Hughes had mistimed his pull shot knew how serious this was. With the forensic wisdom of hindsight, the looks of confusion and distress worn by Brad Haddin, Shane Watson, David Warner, Sean Abbott and others, before the medics arrived, hinted at the grim reality.

Television stations delivered non-stop updates from St Vincent’s Hospital as a shocked audience, stretching well beyond the cricket community, tuned in to see ashen-faced cricketers arriving and leaving, and listen to sporadic one-line updates from Australian team doctor Peter Brukner.

In the hand-wringing helplessness often felt by those affected by someone else’s loss, the nation seized on the solitary public pronouncement from Hughes’s family – that his mother, Virginia, never cared for the abbreviation of his Christian name. From then on, he was referred to as “Phillip”.

Those who could not believe that – in an era of miracle medicine and military-designed protective gear – someone could be mortally struck playing a professional ball sport, wished him a quick road “back on to the park”. But the social media messages posted by team-mates, friends and journalists in the know contained more nuanced references to “thoughts and prayers”. Barely 48 hours after Hughes arrived at hospital, Dr Brukner confirmed the awful truth.

Hughes scored five hundreds for Australia

Hughes scored five hundreds for Australia

From the moment he had collapsed, with his mother and sister watching from the SCG grandstand, Hughes had not regained consciousness. The explanation was delivered with clinical detail via a nationally televised media conference. He had received a blow to the left side of his neck, just below his helmet. The impact crushed the vertebral artery, causing it to split and resulting in a massive brain haemorrhage. It was an injury, Dr Brukner explained, rarely seen by trauma teams. Fewer than 100 cases had been recorded in medical literature, only one inflicted by a cricket ball. In most instances, death had been immediate.

An anguished “Why?” echoed across a country which already knew that talent offered no defence against catastrophe. Within four days in 2006, Steve Irwin, Australia’s best-known nature adventurer, had died when a stingray’s barb pierced his chest, and motor-racing driver Peter Brock had slammed fatally into a tree. Two years before that, cricket had come face to face with needless tragedy when former Test batsman David Hookes was killed after being punched outside a Melbourne hotel.

Shock and sadness accompanied those deaths, yet they involved middle-aged men who had achieved much and were engaged in pursuits carrying a measure of risk: predators, speed, alcohol. What befell a gifted, popular, unassuming young sportsman days before his 26th birthday tapped into a different emotion altogether.

Hughes was barely into adulthood, boyish in stature, demeanour and ambition. And, while clearly possessed of remarkable cricket acumen, he had been in and out of Australia’s Test and one-day sides for reasons the selectors could never properly articulate. He already held a place in the national consciousness: an unfashionable, unorthodox underdog, with a technique hewn from the family’s backyard. One day, most agreed, he would enjoy a fruitful international career.

Hughes was hard not to love. Having been tried and discarded, he would go away and work obsessively on his shortcomings, never bemoaning his ill fortune. Quizzed about these vicissitudes, he would genially assert that numbers, not words, would ultimately speak for him. And those numbers told a powerful tale: he had celebrated more first-class hundreds – 26 – than birthdays.

It was one more reason why the boy who radiated an uncomplicated country-town warmth, whose dad was a banana-farmer-cum-cattle-breeder and whose mum came from a tight-knit Italian family, had been held so close to the nation’s heart.

He was every family’s cheeky little brother; the kid everyone knew at school because he had something special; the one next to whom starry-eyed youngsters wanted to be photographed, not only because he was roughly their height, but because he had blazed the path they dreamed to follow.

Australians prepared for the funeral by following the example of Sydneysider Paul Taylor and putting out their bats, by letting out their emotions, by sitting wistfully through heart-rending video montages of a life played out in the most public of theatres. And uneasy conversations began to form about cricket’s reshaped landscape.

63 not out forever

63 not out forever

Should the first Test against India, scheduled to begin at Brisbane the day after the funeral, be played in his honour, postponed, or cancelled? Should protective equipment be upgraded? Should bouncers be outlawed?

Other compelling narratives ran parallel to the tragedy. One involved a man who had polarised opinion while holding the most recognised sporting office in the nation: Test captain Michael Clarke. Another was about an up-and-coming cricketer from beyond Sydney’s north-western suburbs who was largely unknown until (along with Hughes), he was picked for a limited-overs series against Pakistan in the UAE the previous month: 22-year-old all-rounder Sean Abbott.

The 5-0 pummelling of England, and Clarke’s series-defining century in Cape Town – where he endured an assault that broke his shoulder and almost his thumb – had, in his own words, convinced Australians he was indeed “a tough cricketer”. But where he still differed from those salt-of-the-earth dads who preceded him – Allan Border, Mark Taylor, Steve Waugh, Ricky Ponting – was his off-field characterisation.

In an age of flagrant self-promotion, Clarke happily (too happily, for some) flaunted a publicity-aware model wife, a newly acquired mansion in Sydney’s harbourside millionaires’ row, a yen for designer accessories and lifestyle, and a continued absence of progeny. Upon inheriting the leadership from the no-frills Ricky Ponting, Clarke had spent years attempting, with wavering success, to put right the tabloid-driven perception of him as glibly superficial, the blue-collar boy who had supposedly become the image-obsessed metrosexual.

What Australians came to learn was that Clarke’s commitment to his cricket family ran far deeper than a shared vocation. And there was nobody to whom he felt a closer bond than Hughes. When Hughes quit his final year of secondary school to move to Sydney for cricket, he and Clarke shared the same coach. Hughes then followed Clarke to his grade club, Western Suburbs. And on tour the pair were so inseparable that some counselled Clarke to devote more time to building relationships with others in his team.

Clarke could accept the wisdom of the advice, but reasoned that he simply preferred Hughes’s company. Hughes referred to team-mates, colleagues and acquaintances uniformly as “brus”, which equated in street slang to “brother”. And, within the inner sanctum of Australian cricket, Clarke viewed Hughes as the little brother he never had. It was a reciprocal relationship.

Throughout the ordeal that Clarke shared with the Hughes family over two haunting days at St Vincent’s, then through the memorials that followed, Australians were privy to a raw, human and disarmingly honest portrait of their pre-eminent cricketer. The sensitivity, courage and dignity Clarke carried through every sob-filled public appearance as spokesman for the Hughes family, his team and his country – culminating in his deeply personal funeral eulogy – altered the way in which he was viewed. He was no longer simply Australia’s captain: he was unequivocally their leader.

If Clarke was the public face of the tragedy, then Abbott was at risk of becoming its silent victim. Yet the communities that threw their arms around Hughes’s family, home town, team-mates and friends also made a point of ensuring Abbott was clasped tight in the group hug.

Michael Clarke – Australia’s leader

Michael Clarke – Australia’s leader

It’s difficult to hypothesise how the scenario might have played out had it happened in the international arena, the fatal ball delivered by a rampaging English, West Indian or South African quick. The near-riot at Adelaide during Bodyline might provide some kind of starting point.

But the fact that it was a domestic affair meant there was no callous blame or condescending judgement attached to Abbott. Like Hughes, he had simply been doing his job. Abbott’s return to cricket for New South Wales at the SCG in the weeks that followed Hughes’s funeral was widely welcomed; against Queensland he had second-innings figures of 6-14. But his path to the bountiful career that had seemingly beckoned is now strewn with unknown obstacles.

The first Test, destined to be played in shadow, was rescheduled for Adelaide, the city to which Hughes had gone in 2012 to revive his international hopes. The move was seen by most as a pragmatic compromise between timely tribute and an acceptance that the world would keep turning.

Adelaide is usually the most sociable date on Australia’s Test roster, full of aesthetics, food, wine and an appetite for cricket’s most authentic form. But the game that began on December 9, five days after Hughes’s private cremation, wore an unfamiliar coat.

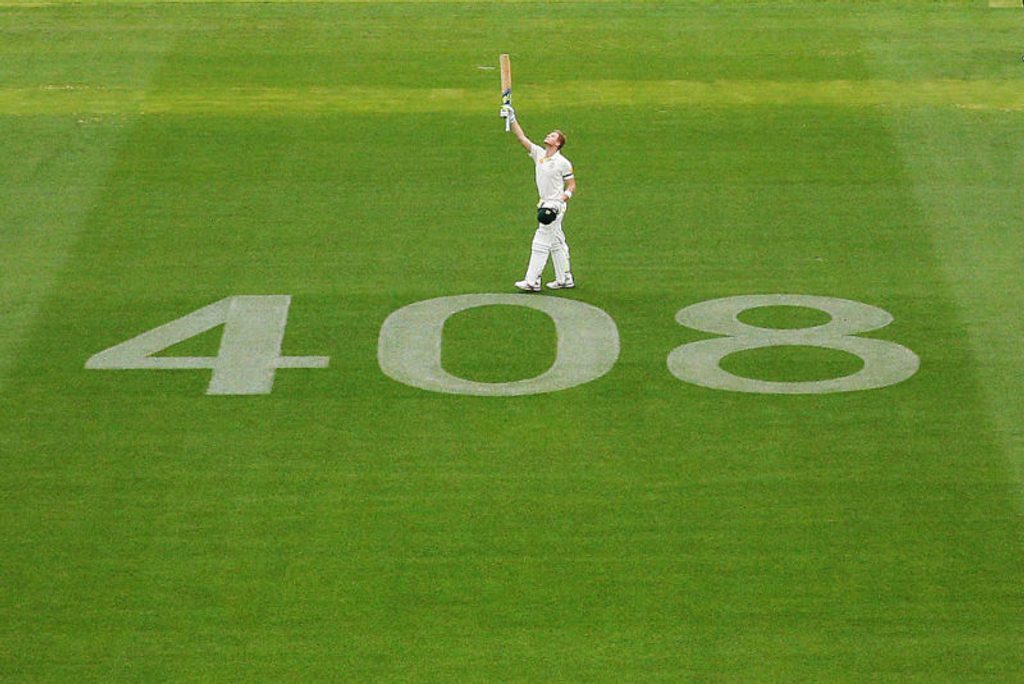

Steve Smith celebrates his century against India by the emblazoned 408 – Hughes’ Test number

Steve Smith celebrates his century against India by the emblazoned 408 – Hughes’ Test number

The brilliant Adelaide sunshine was there on the opening morning, but it only partially warmed souls who felt a chill during the video tributes, at the emblazoning of his Test number (408) on the outfield, through the 63 seconds of poignant applause (Hughes’s score when he was hit), and at the sight of his name on team sheet as Australia’s eternal thirteenth man. The normal hubbub was replaced by a studied silence: many seemed unsure how to behave. It was part Test match, part open-air memorial service.

A volley of David Warner boundaries helped quell the unease. But a sharp collective intake of breath greeted the day’s first bouncer, before prolonged applause broke out when the team, and later a couple of batsmen, reached 63. Gradually, as the game’s momentum built and subplots unfurled, it became an occasion to celebrate, not just commemorate.

The panicked concern of the Australian players when India’s captain Virat Kohli was struck on the helmet by Mitchell Johnson eventually gave way to heated verbal exchanges as competitive instincts took over. Come the next Test at Brisbane, then the Boxing Day fixture at Melbourne, the number 63 was recognised by only a smattering of spectators. The use of ruthless short-pitched bowling returned, and was deployed unashamedly by both teams. And, when Johnson again rifled a ball into the protective grille of Murali Vijay, he made a cursory visual check, from a distance, to ensure he was unhurt; only one member of Australia’s slips cordon checked on Vijay’s wellbeing.

An inextinguishable legacy

An inextinguishable legacy

Within a month, the notion that international cricket’s nature would be indelibly changed was exposed as naive. The game will go on, although its rhythm is destined to skip a beat every time a player is struck with force, or a doctor sprints from the dressing room.

But in Sydney, in Adelaide, in Macksville, and in those other pockets where Hughes’s spirit burns within men and women and boys and girls playing cricket at their local ground, on the beach, in their backyard – in all those places a new awareness of just how ephemeral each innings can be surely now resides. That will remain Phillip Hughes’s inextinguishable legacy.

Read more Almanack articles.

Previously from the almanack: Beefy & Viv: Great friends & cricketing immortals