Richard Hobson is a freelance cricket writer. He covered the game for more than 20 years at The Times, and now gives guided tours of Oxford. This article features in the 2019 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, which is available to buy here. The most famous sports book in the world has been published every year since 1864.

After the slaughter on the battlefields of the First World War, Britain was desperate for normality – including the return of county cricket. In a fascinating piece from the 2019 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Richard Hobson charted the game’s faltering new beginning.

Nearly five years after the lamps went out all over Europe, the County Championship returned to life on a crisp morning in mid-May. It was 1919. Across the Channel, world leaders were plodding towards a peace deal at Versailles. Further east, the Red Army were consolidating Bolshevism in Russia. Back at The Oval, and to rather less fuss, roughly 6,000 spectators watched Jack Hobbs score twin half-centuries for Surrey against Somerset, while half that number saw Middlesex and Nottinghamshire share 438 runs and 15 wickets at Lord’s on the first day alone. “The famous ground looked all the better for its long rest,” said the Times.

[caption id=”attachment_93716″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Jack Hobbs, 1925[/caption]

Jack Hobbs, 1925[/caption]

In truth, Lord’s had not enjoyed much more rest than other cricket grounds during the First World War. The Long Room had been used to make string haynets for horses, and stretchers for casualties on the Western Front. Elsewhere, pavilions had been used as hospitals: 3,553 wounded servicemen were treated at Trent Bridge, while Old Trafford needed fumigating to get rid of the stench of the sick. Taunton had become a farm, Grace Road a training ground for mules. For those grim years, cricket understood its place.

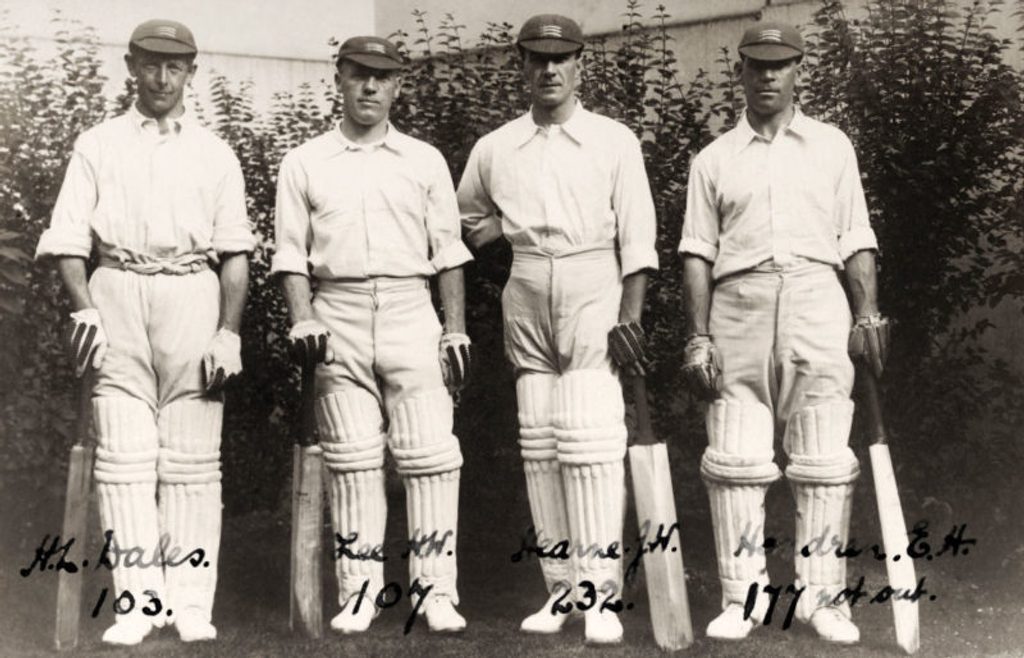

With 407 first-class players decorated for gallantry, no team lacked a returning hero. On that first day at Lord’s, Nottinghamshire’s Arthur Carr, trapped for three hours under a dead horse during early skirmishes at Mons, was bowled by Captain Nigel Haig, a recipient of the Military Cross. Harry Lee, the Middlesex opener, had been declared dead in 1915, and a memorial service held in his name; in fact, he had been discovered alive by the Germans between the lines three days after being shot. “I was lucky,” he wrote. “Many splendid men were given no second innings.” In all, 289 first-class cricketers perished. Hampshire alone lost 24, but every county mourned at least three. “These men do not die,” wrote the Times, “for their fame is immortal.” It was a nice line, but sooner or later clubs had to be pragmatic; immortality does not score runs or take wickets.

[caption id=”attachment_112718″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Middlesex batsman Harry Lee, (second from left)[/caption]

Middlesex batsman Harry Lee, (second from left)[/caption]

The countdown to a resumption of the Championship began a day after the signing of the Armistice, on November 12, 1918, when MCC summoned a meeting of the Advisory County Cricket Committee. They had plenty to ponder. A piece in the Times proposed banning left-handed batsmen for being “a thorough nuisance and a cause of waste of time”. While accepting the style and brilliance of Frank Woolley, the piece continued: “No child surely is so left-handed that he cannot learn to play right-handed if he starts young enough.” The Manchester Guardian observed: “Some [ideas] have been temperate, others wild and fantastic to the point of madness.”

Delegates gathered on December 16 at the Midland Hotel in St Pancras, where the meeting was said by one critic to lack “the calm and judicial atmosphere of the Committee Room at Lord’s”. The counties decided to return to the normality of peacetime by way of the abnormal, agreeing to shorten matches from three days to two: 11.30 to 7.30 on the first day, 11 to 7.30 on the second, the ultimate goal being brighter, quicker cricket. Tea lasted ten minutes, and refreshments were taken on the field. Lancashire proposed the motion, and Lord Hawke, the MCC president who chaired the meeting, pleaded unsuccessfully with counties to oppose it: “What amateur is going to arrive at his hotel for dinner at nine o’clock?”

This being English cricket, the meeting proved merely a staging-post. A month later, Plum Warner predicted “disaster and discontent”, describing the two-day format as “almost Prussian” in its demands on the players. As concern mounted, the counties had a rethink, this time at the Sports Club in St James’s Square. They huffed and puffed, before sticking with plan A, making a sole concession to the arduous playing hours by extending tea to 15 minutes. Warner remained unconvinced: “It seems to be too much of an American hustle.” Meanwhile, Lord Harris, still the most influential figure at MCC, took a Machiavellian approach that has remained in fashion in cricket administration ever since: abject failure would be a small price if it means the idea is kicked into touch.

Squads assembled in April, with Lancashire’s preparations hampered by snow. Yorkshire remained best equipped, boasting 40 amateurs and professionals. Finances were relatively sound: enough members had stayed loyal through the conflict, even with play no more than a dream. Only Worcestershire of the 16 pre-war contestants opted out (Glamorgan didn’t gain first-class status until 1921). Because of the lop-sided fixture list, placings were calculated on the percentage of wins; Yorkshire played 26 games, the poorer resourced Somerset and Northamptonshire 12.

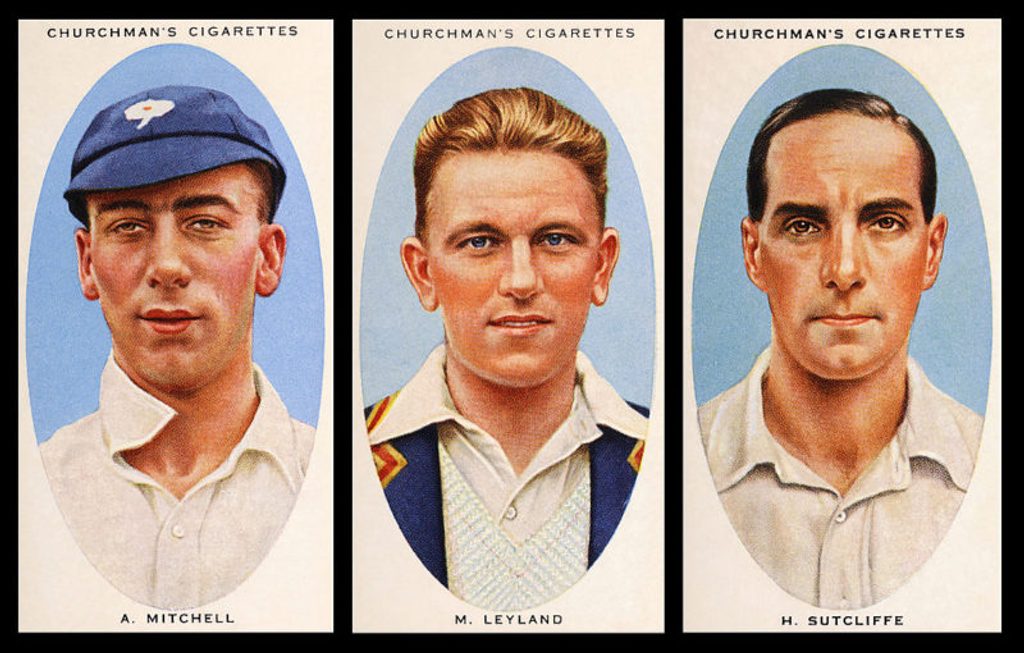

[caption id=”attachment_112792″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Herbert Sutcliffe went on to have a mightily successful England career[/caption]

Herbert Sutcliffe went on to have a mightily successful England career[/caption]

Of the newcomers, Herbert Sutcliffe was much the most successful; for others, careers proved short. Having taken a wicket with his first ball, Kent’s Gerald Hough soon realised that war wounds restricted his off-spin, and he never struck again. Arthur Denton of Northamptonshire was permitted to bat with a runner, having lost a leg in 1917 (a cork and leather replacement allowed only limited mobility). But Colonel Alexander Johnston found less charity. Wounded four times, mentioned in despatches five, and a recipient of the Croix de Guerre for action at the Somme, he made one limping appearance for Hampshire, before being drummed out of the county game.

Entertainment became a watchword. Although 1890–1914 has been described as cricket’s Golden Age, it had lost some of its glint because of slow play. Counties feared crowds would diminish further after losing the habit. The object of the game, as Old Etonian Sir Home Gordon said before the season began, was “not to occupy the wickets as passively as though the batsmen were in the trenches”. When Derbyshire and Leicestershire managed a combined 392 for 16 on the first day, in August, the Times headline still read: “Dull Play at Chesterfield.”

The most colourful and contentious incident of the season involved Harold Heygate, an opener who had last appeared for Sussex in 1905. Now 34, and wracked by rheumatism, he found himself in Taunton, with Sussex a man short to face Somerset. Having been dismissed for a duck by Jack White on the first day, Heygate – who batted at No. 11 and didn’t bowl – spent the second, according to David Foot, sitting “morosely in his blue suit, rubbing his throbbing knee and hoping his county would not need him”.

They did. Requiring 105 to win, Sussex lost their ninth wicket on 104 – and there was no sign of the last man. Just as umpire Alfred Street drew the stumps, Heygate hobbled into view, bad leg dragging behind good, still wearing blue serge jacket and trousers, plus waistcoat and watch chain. Street reinserted the stumps, only for Somerset’s senior professionals, led by Len Braund, to persuade White – the amateur captain – to cry foul. Street felt he had no option but to call an end to proceedings for the second time, and declare a tie. Heygate, having taken four minutes to reach the crease, could only wince and retrace his steps. With no specific timed-out law back then, debate raged for several days on the sportsmanship of the incident, before MCC ruled that Street had acted correctly. The tie stood, and Heygate’s career was over.

Concerns about the public appetite were assuaged, with people grateful for a diversion after wartime austerity. Outside cricket, heavily starched collars were starting to loosen, and a mood for greater equality continued to grow. Women, or at least some of those over 30, had been given the vote in 1918. David Lloyd George’s coalition government had been returned to power on a programme of reform in public health, education and housing. Strikes became common, and the upper classes bemoaned a dearth of domestic servants. But social change in cricket was harder to detect: if the crowd at the second day of the Eton–Harrow centrepiece at Lord’s appeared slightly down on the first, it was primarily due to its clash with a garden party at Buckingham Palace (the King had dropped in to see the match on the opening morning).

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

Despite increased admission charges caused by the widely loathed entertainment tax, more than 100,000 watched play over the Spring Bank Holiday. In August, around 18,000 at The Oval saw the first day of Hobbs’s benefit game, postponed in 1914 when the military took over the ground. Cricket had faced criticism in those early weeks. That summer’s Championship was not brought to an immediate close upon declaration of war – only later, when the loss of players to action made selection unfeasible, and public opinion hardened, shaped not least by W. G. Grace.

Come 1915, players scarcely used the Oval nets because they were afraid of jeers from men on the passing trams. Yet some of the most famous names, including Hobbs, continued to turn out in a strong Bradford League, well away from what Wilfred Owen described as “the monstrous anger of the guns”. Hobbs, who opted to serve on the home front, was quickly forgiven.

Cricket in 1919 became a barometer for the health and cohesion of the nation, and the Canterbury Festival in August drew particular attention. “One by one, the old pleasures that the war banished for five years are coming back,” said the Times, noting the marquees ringing the ground, flags and Chinese lanterns in surrounding streets, and the Old Stagers performing their 74th season at the Theatre Royal. Ladies Day was deemed a success: “The skirts of today do not trail, and whether they cover age or youth they are uniformly short and brilliant and diaphanous.” Work on a memorial to the Kent and England left-arm spinner Colin Blythe, who died at Ypres, was not finished in time, and it had to be unveiled a fortnight later.

[caption id=”attachment_112749″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Sussex take the field at Hastings, 1919[/caption]

Sussex take the field at Hastings, 1919[/caption]

By then, Kent were Yorkshire’s strongest challengers. They had beaten Sussex in a day at Tonbridge, and were praised for their conduct during Hobbs’s benefit game, when Surrey needed 95 to win in 42 minutes. Kent not only continued to play in heavy drizzle, but refused to slow the over-rate, and were in the 13th when Surrey won with ten minutes to spare. The title was decided only in the final minutes of the season. Yorkshire’s draw against Sussex meant Kent had to beat Middlesex at Lord’s. Rain allowed only 90 minutes on the first day, and made for a treacherous pitch on the second. Having stretched their total to 196, Kent dismissed Middlesex for 87, then reduced them to 86 for eight following on, with 15 minutes to claim the last two. Middlesex held firm, enabling Yorkshire to win the first of 12 titles in the 21 interwar years.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

Poignantly, one of their new stars was left-arm seamer Abe Waddington; three years earlier, on the opening day of the Somme, he had sheltered in a crater, wounded by shrapnel, to comfort his childhood hero Major Booth as he died in his arms. Another leading light of Yorkshire’s 1919 team, Roy Kilner, had sat in agony behind the lines receiving treatment on a wrist shattered only minutes earlier. Booth had been best man at Kilner’s wedding. Alongside the Championship, an Australian Imperial Forces touring team played 28 games, underwritten by the military authorities (hopes for a three-match Ashes were scrapped because of a lack of time). Herbie Collins soon replaced the quarrelsome Charlie Kelleway as captain, while other distinctive names included Jack Gregory, the fastest bowler of the season and future scourge of England, and Bert Oldfield, the long-serving wicketkeeper who had been found semi-conscious and partially buried near Ypres in 1917 in an attack that killed three of his comrades.

[caption id=”attachment_112779″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] The Australian team takes the field during the first Ashes Test at Trent Bridge, 1921[/caption]

The Australian team takes the field during the first Ashes Test at Trent Bridge, 1921[/caption]

When the tour ended with defeat at Scarborough by C. I. Thornton’s XI, inspired by Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes, some thought back to the Melbourne Test of 1911-12, when the same pair put on 323 for the first wicket. But the fitness and consistency of the Australians warned of the series in 1920-21 and 1921, when they beat England 5–0 and 3–0. Australia had suffered fewer losses during the war, and MCC had turned down an invitation to tour there in 1919-20 because they did not feel ready. As the Guardian said presciently: “It is certain that we shall find our work cut out to keep the Ashes from changing hands.”

By September, the same newspaper felt able to declare that cricket “has triumphed over the organised attempt to dethrone it”. New, or nearly new, players had stamped a mark, including Cec Parkin, Tich Freeman and Sutcliffe, while the likes of Hobbs, Rhodes and Woolley continued to match pre-war standards. But the physical demands of two-day cricket proved too much. “It has turned a pleasant, invigorating sport into a laborious, exacting and exhausting task,” said Hobbs, noting how inferior batsmen took easy runs off tired bowlers and fielders. A lack of pace was especially conspicuous. And so, even before the season had ended, the counties accepted their error and voted to return to three-day cricket for 1920. Lord Harris could smile as the hands were counted.