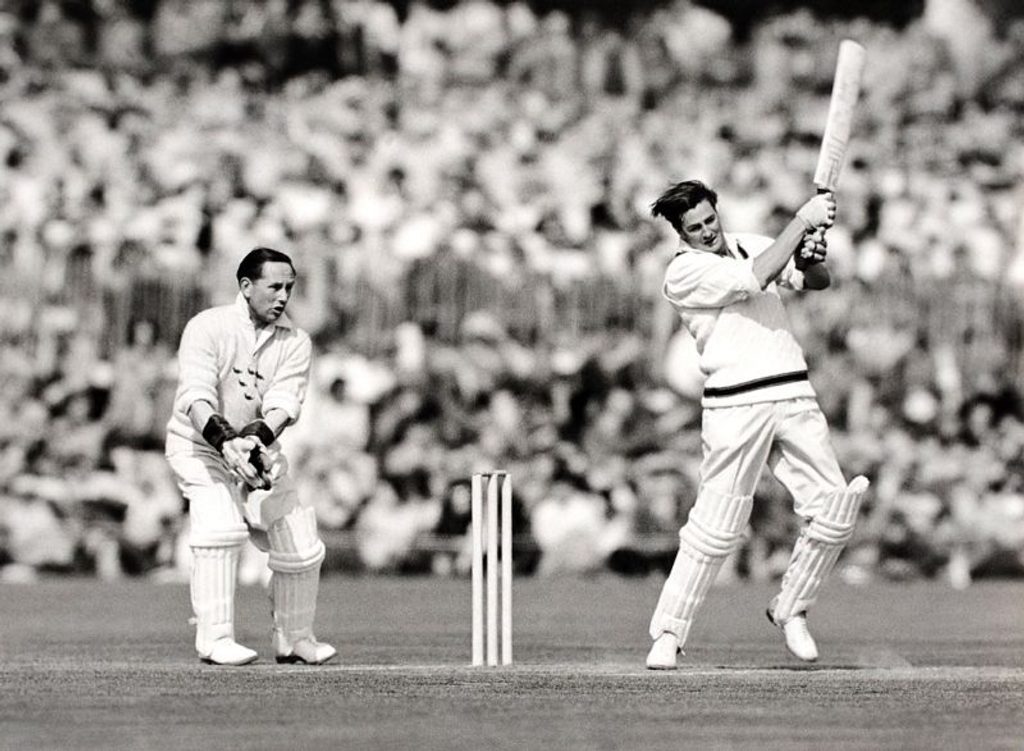

Keith Miller, the Golden Nugget, was much more than one of Australia’s greatest all-rounders. He was a Hollywood hero who illuminated the game in the years after the war.

He was, Neville Cardus wrote, “Australia in excelsis”. Free-spirited, generous, sometimes bloody-minded, altogether bonzer, Miller was the most colourful cricketer of his post-war generation, driving sixes beyond imagination, bowling fearsomely fast and catching with a predatory instinct, playing to and for the crowd. Off the field, his zest for life and natural charm attracted friendship from every quarter, be it country house or street-corner bar. He was, moreover, Hollywood handsome, over six feet tall, broad-shouldered, with dark brown hair worn longer than the times approved. Little wonder women wanted to be with him and men wanted to be him.

Associated mainly with New South Wales and captaining them to three successive Sheffield Shield titles, Miller was, in fact, Melbourne-born and raised. He was named after Australian aviators Keith and Ross Smith who at the time were making the first flight from England to Australia. His hard-hitting batting for South Melbourne led to selection for Victoria Second XI while he was still attending Melbourne High, where Bill Woodfull, the former Australian captain, taught maths. Miller’s earlier dreams of becoming a jockey had been dashed when he grew almost a foot taller in his mid-teens, although those extra inches did give him the physique to star in Australian Rules football for St Kilda and win state honours. Not that the lure of the track ever left him; odds always mattered more than averages.

Two months after turning 18, in 1937-38, he made an impressive if restrained first-class debut, scoring 181 (with only five fours) against Tasmania at the MCG. But his Shield debut was held back another two years until 1939-40. He made a century when South Australia came to Melbourne, but war soon took priority over cricket, and in 1942 Miller enlisted in the RAAF, qualifying as a pilot. A stopover in America en route to England led to him meeting his first wife Peg. By night, “Dusty” Miller flew first Beaufighters and then Mosquito fighter-bombers in raids over Germany; on summer days, he played cricket. “Flight Sergeant Keith Miller … revealed the ability and temperament of a champion and showed every promise of developing into one of Australia’s best all-rounders,” Wisden forecast in 1944.

“Free-spirited, generous, sometimes bloody-minded, altogether bonzer”

“Free-spirited, generous, sometimes bloody-minded, altogether bonzer”

He had left Australia little more than an occasional bowler. When Lindsay Hassett’s Australian Services team set sail for India in 1945, Wisden was rating Pilot Officer Miller “the liveliest opening bowler seen in England during the summer”. There were eulogies, too, for his upright, full-flowing batting that had The Times correspondent musing whether Lord’s was big enough for his mighty hitting. Unimpressed with Lord’s on first sight – a crummy little ground, he thought – he subsequently blessed it with his best. His three hundreds there in 1945 included a magnificent 185 to set up the Dominions’ victory over England. The first of his seven sixes carried to the top tier of seats between the Pavilion turrets; an on-drive crashed into the roof of the broadcasting box above the England dressing-room. Albert Trott’s unique 1899 drive over the Pavilion was mentioned in despatches and Miller returned home with a brand new name: “Nugget”, the golden boy.

The first of Miller’s 55 Tests – the 1946 annihilation of New Zealand at Wellington – was not recognised as such until March 1948. By then he had returned Test-best figures of 7-60 at Brisbane against England, made a maiden Test hundred at Adelaide, and forged the hostile pairing with Ray Lindwall that spearheaded Bradman’s Invincibles through England in 1948. At least Lindwall was orthodox. All a batsman had to think about was searing pace, late swerve, skiddy bouncer, the phalanx of fielders behind the bat and a new ball every 55 overs. Miller was unpredictable. A pitch-perfect ball, snaking off the seam, might easily be followed by a leg-break or googly or a round-arm off-cutter. His run-up comprised nine easy paces – ostensibly. As likely as not he would come off a few yards and let loose a snorting bouncer that sucked the crowd breathless – or, when he bounced Len Hutton five times in eight balls at Trent Bridge, encouraged a protracted chorus of booing. Miller’s response was a toss of his thick mane and, next day in atrocious light, bumping Denis Compton, supposedly a mate, back on his stumps to end a rearguard innings of 184.

But his seven Trent Bridge wickets had a price. Miller’s pace, the product of immense torque, put a terrible strain on a back damaged when he crash-landed late in the war. (Bored with hanging about the airfield, he had taken his mechanic up for a “flip” and an engine caught fire. “Nearly stumps drawn that time, gents,” he said as they walked away from the wreckage.) He did not bowl at Lord’s or in the first innings at Old Trafford. When Bradman threw him the ball, Miller tossed it back, kindling rumours of a rift between them and embellishing the rebellious Miller image. He took only six more wickets in the series, and failed to top his 74 at Lord’s.

Who cared? His style counted more, contrapuntal to Bradman’s relentless advance into immortality. “He’ll learn,” Bradman muttered to Trevor Bailey at Southend after Miller, coming in at 364-2, disdained the plunder and gave his wicket away first ball. Bradman was wrong. War, and with it the death of friends, had taught Miller there was more to life than easy runs. But Bradman, godfather of Australian cricket, was unforgiving. Miller was omitted from the 1949-50 side to South Africa. And for all his success as New South Wales captain, he was never appointed to lead his country in Tests. The stories of Miller telling his players to “scatter”, instead of setting a field, masked New South Wales’s pre-match planning and his intuitive leadership.

Bill Johnston’s motor accident early in the South African tour got Miller there as a replacement, and he played in all five Tests. One of his six sixes against Eastern Province travelled some 130 yards before splashing into the St George’s Park duck pond. When MCC toured in 1950-51, he headed Australia’s batting averages and was second in the bowling behind mystery spinner Jack Iverson. “Good as they were,” Wisden said, “figures could not indicate Miller’s worth to Australia.” West Indies buckled before the Lindwall-Miller-Johnston pace barrage in the 1951-52 “cricket championship of the world”, but a year later Jack Cheetham’s young South Africans arrested Australia’s momentum in a drawn rubber.

England would have the upper hand in Miller’s last three Ashes series. He began the 1953 tour with 220 not out at Worcester and closed with 262 not out against Combined Services; in between, he put Australia in a winning position at Lord’s with a selfless 109, only for Bailey and Watson’s famous stand to thwart them on the final day. But his ten wickets at 30 in that series were his costliest yet, as were his 20 at 32 in the Caribbean in 1954-55. Those, however, came in a winning cause given impetus by his three centuries. In the First Test at Kingston he also led Australia to victory after Ian Johnson injured his foot on the second day.

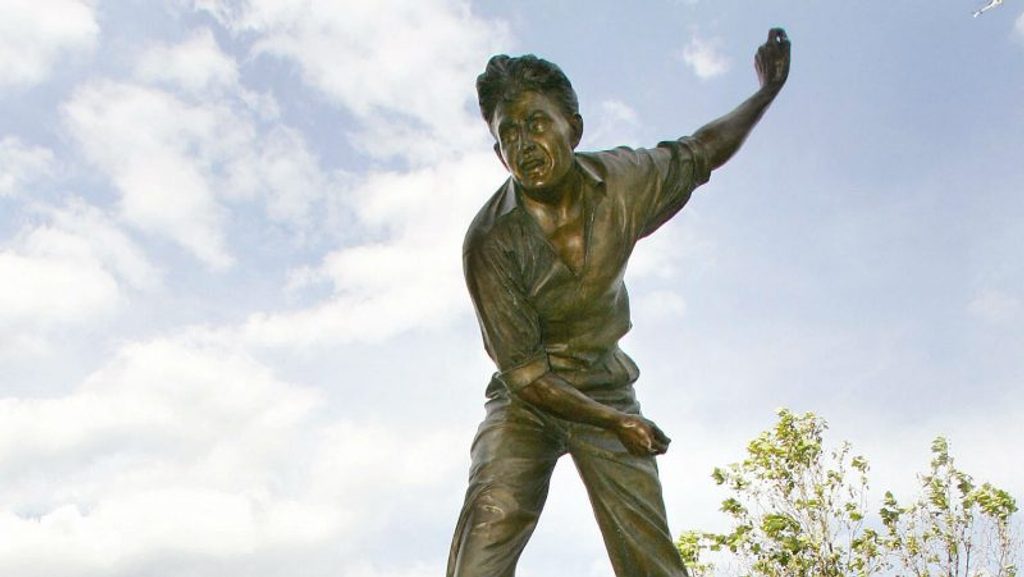

The Keith Miller statue at the Melbourne Cricket Ground

The Keith Miller statue at the Melbourne Cricket Ground

But the West Indies pitches were easy-paced, and the home attack had no one approaching the speed of Tyson and Statham, who had recently rolled Australia over at home. In 1956, Jim Laker and spin-friendly pitches made Miller’s final tour a nightmare, reducing his classical batting to mockery as hair, pad and bat flopped forward in futile defensive lunges. Yet there were consolations. At Lord’s, ignoring his 36 years, he bowled Australia to victory with peerless fast-medium bowling and his only ten-wicket return in Tests. It came as no surprise to teammates who, seven months earlier, had witnessed his 7-12 demolition of South Australia at Sydney; showman to the last, he acknowledged the Lord’s ovation by picking the umpire’s pocket and tossing the bails into the crowd.

A fortnight later, while captaining the tourists against Hampshire, he was invited to nearby Broadlands by Lord Mountbatten, whose guests included Princess Margaret. Miller had met the princess in 1948 when the Australians visited Balmoral; now he found himself being asked to sit beside her during the after-dinner film. “The bluest eyes I have ever seen,” Miller noted, but rumours of an affair gained no currency from him. “No gentleman ever discusses any relationship with a lady,” he chastised the curious.

He continued to visit England every summer, working initially as a journalist for the Daily Express, maintaining friendships and pursuing his love of classical music. A cousin had introduced him to Beethoven early on – returning from a wartime mission he reputedly diverted over Bonn to see Beethoven’s birthplace – and music, as much as cricket, was integral to his friendship with Sir Neville Cardus. Hallé maestro Sir John Barbirolli wrote the foreword to one of Miller’s books. But passing years and ill-health took their toll, and he was wheelchair-bound when the statue of him at the MCG was unveiled in February 2004. It didn’t matter. The legend and the memories were intact; the mourners who packed Melbourne’s cathedral for his state funeral testified to that.

Miller, Keith Ross MBE, AM, died on October 11, 2004, aged 84.

NUGGETS

“A young eagle among crows and daws.”

Sir Neville Cardus

“He’s the best all-rounder, along with Garry Sobers, who ever lived.”

Alan Davidson

“He could bat, bowl, field, and he could fly an airplane.”

Bill Brown

“Keith was a genuine legend. He understood that the game, great as it is, is just a game, and he played it that way.”

Bob Merriman, chairman of Cricket Australia

“Sorry, Godfrey, but I have to do it – the crowd are a bit bored at the moment.”

Miller’s apology after bowling successive bouncers to Evans in 1946-47

“I’ll tell you what pressure is. Pressure is a Messerschmitt up your arse. Playing cricket is not.”

Miller on the modern game

“No regrets. I’ve had a hell of a good life. Been damned lucky.”

Miller at 75