This Wisden obituary paid tribute to the extraordinary life of legendary commentator and writer John Arlott.

Arlott, Leslie Thomas John, OBE, died at his home on Alderney on December 14, 1991, at the age of 77.

Few men who have concentrated the interests of a lifetime on cricket have commanded as wide and thorough a knowledge of the game as John Arlott. When he was doing commentary, or composing a portrait of a Tate or a Trueman, or writing a match report for The Guardian, he was at or near the centre of affairs.

But he was equally an expert on interests connected with the game: its vast literature, extensive history and collection of artefacts were all within his purview. To fuel his activities he had great energy, the ability to work at speed, and the charm to elicit information from whatever source he was investigating.

Add in the fact that he was a poet of some stature and that he enjoyed the laughter and company of friends, whom he loved to entertain in the most civilised way, and you have a man of deep humanity.

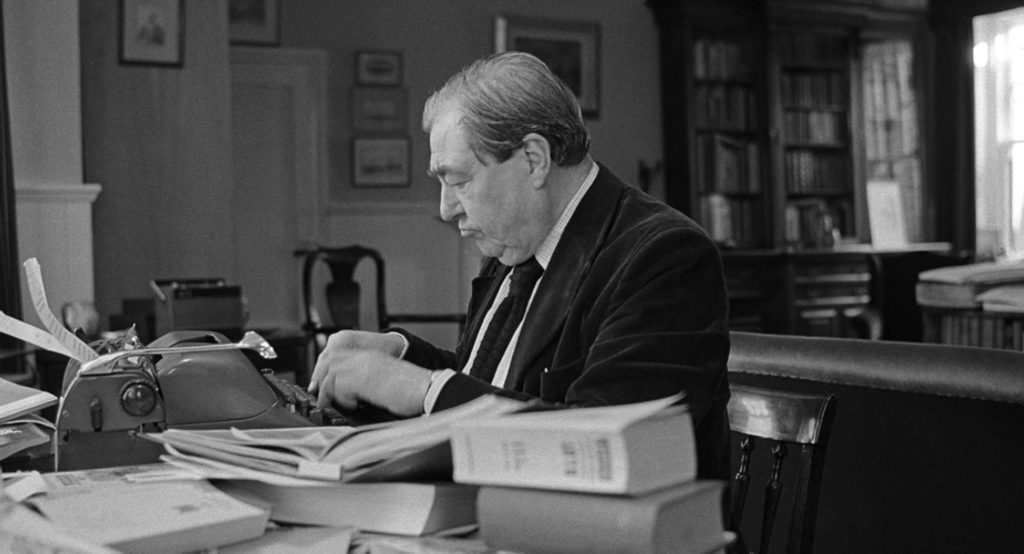

Arlott in ‘The Old Sun’ – his home – in 1979

Arlott in ‘The Old Sun’ – his home – in 1979

J.A., as he perhaps over-modestly referred to himself in his autobiography, went to his first school in Basingstoke in 1920 when he was six. He soon located the cricket ground, and seeing mysterious white figures parading before him demanded to know what it was all about. His father, a patient, careful man, was pestered into providing rudimentary equipment. (Despite his early start he never became much of a player.)

Six years later he made his way to his first big match, England v Australia at The Oval, where he saw Hobbs for the first time and recognised his genius. He was later to found a dining club in honour of the Master. That was his ration for the year, but it made an enormous impression on him.

In 1927 he saw the whole of Sussex v Lancashire at Eastbourne, and soon he was reading anything he could lay his hands on about cricket. Cardus the reporter and Cardus the author were greedily digested. Good Days and Australian Summer, masterpieces both, were woven into the very fabric of his being. But where was this first love leading? How was he, a humble copper when war broke out in 1939, to fashion a career out of cricket?

Arlott’s prospects of achieving a breakthrough into the magic circle were enhanced by an extraordinary chain of events which happened to unite his several talents with his love of cricket. In 1945 he was a police sergeant, in Southampton, but the broadcast address he made to His Majesty on VE Day on behalf of the police was the catalyst.

By “sheer luck”, as he himself admitted, he was introduced to all the right people behind the scenes at the BBC, and the offer of a permanent post followed. In time he was asked if he would like to do commentary on the first two matches of the Indian tour in 1946, provided they would not interfere with his job as Overseas Literary Producer.

His broadcasts from Worcester and Oxford went down very well in India, and to his delight he was given the chance to cover the whole tour, including the Test matches. At Lord’s, where the First Test was played, he was given the cold shoulder by his colleagues in the commentary box, resentful of the upstart who in their eyes had made off with the top job. But he survived and earned a grudging respect.

Moreover, the public had begun to take note of a new and utterly individual voice coming over the air describing cricket. In the war the voice of Churchill had been a symbol of defiance, rousing ordinary folk to great deeds. Now the voice of Arlott brought comfort and reassurance as they adjusted to the ways of peace.

His commentary technique was strongly influenced by his poetic sense. With the economy of a poet he could describe a piece of play without fuss or over-elaboration, being always conscious of its rhythm and mindful of its background. He was never repetitive or monotonous, except for effect. The listener’s imagination was given free rein. From 1946 till the end of the 1980 season he covered every single home Test match. The voice may have dropped an octave as the years rolled by, but the level of commentary never faltered.

When the editor asked Arlott to write an appreciation of Neville Cardus for the 1965 edition of Wisden, he chose wisely, for Arlott was a natural disciple of the man who was 25 years his senior. The two men had much in common: they were both incurable romantics; they both combined a love of cricket with a love for the arts (music and poetry); each had a favourite county; they were both largely self-educated and had frequented libraries in their youth.

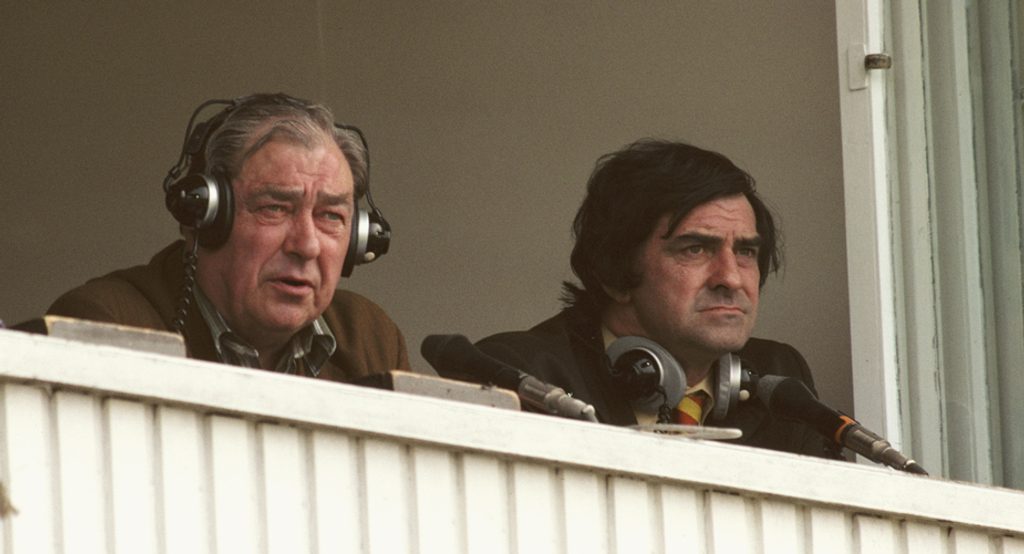

John Arlott and Fred Trueman share the commentary box during the 1979 Cricket World Cup

John Arlott and Fred Trueman share the commentary box during the 1979 Cricket World Cup

From humble beginnings they both enjoyed the turn of fortune’s wheel at a critical stage of their development. Arlott’s debt to Cardus was immense. He saw that Cardus’s cricketers were no mere cardboard figures performing complicated routines on a distant stage, but real, live human beings with hearts and minds and feelings. Cardus got close to his Lancastrians, but Arlott got even closer to his men from Hampshire and wrote about them with deep affection.

He liked a character, especially the honest toiler who laboured often with little reward. His portrait of Vic Cannings is a typical example. But his study of Trueman, written in a fortnight during the postal strike in 1971, shows what he could do when his batteries were fully charged. As a piece of descriptive writing, this extract is hard to beat:

It sounds like an express train thundering past, all pistons firing – steam of course.

Arlott was no great traveller; he preferred to stay at home in winter and watch some soccer. He covered the 1948-49 MCC tour to South Africa and was appalled by what he saw under the surface. He became a fervent opponent of apartheid and was responsible for Basil D’Oliveira’s coming to England to play. His one visit to Australia was in 1954-55, when the Ashes were retained under Hutton. Apart from these two ventures, his main journalistic job was to be The Guardian’s chief cricket correspondent from 1968 to 1980.

In addition to all his other services to cricket, he was one of the leading authorities on its past. He was both archivist and historian. In 1963 he was commissioned to write a review of the “Cricket Literature of the Wisden Century”. It was wide-ranging and is still a useful guide. In the Barclays World of Cricket, he contributed two major articles, on Art and Histories. Both serve to illustrate the amazing comprehensiveness of his knowledge. From the 1950 edition of Wisden until this one, except for 1979 and 1980, he provided a comprehensive review of books published in the preceding year.

Arlott at the home in which he retired, pictured in 1984

Arlott at the home in which he retired, pictured in 1984

Arlott, the Liberal politician, always had the interests of the English county player at heart. The strong bond between them was cemented when he became president of the newly formed Cricketers’ Association in 1968, at a time when cricket seemed to be in danger of disappearing as a major spectator sport. Salaries had failed to keep pace with the cost of living and morale was at rock bottom.

Arlott’s democratic views and wise counsel earned him much respect in the cricket world and among the players. His moderation and tact helped in some tight corners, notably at the time of the Packer Affair, when he strove to keep the Cricketers’ Association neutral.

Of all John Arlott’s talents, it is his unique gift for cricket commentary which will bring him lasting fame. And nothing became him more than the manner in which he quietly slipped away from the scene at the end of his final commentary at Lord’s while the crowd stood and, along with the players of England and Australia, applauded. A humble and generous man, he was appointed OBE in 1970 and had Honorary Life Membership of MCC bestowed upon him when he retired in 1980.