Jeremy Coney showed the world his shrewd leadership qualities during New Zealand’s 1983 World Cup campaign and Test series against England. It earned him a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

Jeremy Coney is still recognised as one of New Zealand’s greatest captains, leading them to a first series win in England in 1986. He played in 52 Tests, scoring 2,668 runs at 37.57

Being vulnerable in ways that full-time teams are not, New Zealand rely heavily on attitude and team-work. The major cricketing nations of the world are in business every day, with the result that one of their superstars is usually in form. New Zealand’s balloon floats only when the gases are mixed just right and everyone is fresh, willing and ambitious. They are a team fashioned out of a positive attitude to contest every run, whether batting or bowling. To perform well, every man must do the basic things better than their opponents. In this way they work as a unit.

Jeremy Vernon Coney, born in Wellington on June 21, 1952, epitomises this attitude. As a child of the 1960s he still grants majesty to athletes and innocence to games. Sports are fun. For him, playing for New Zealand matters most. So long as the majority of the New Zealand team feel this way they are aware that miracles may occur.

In many ways Coney represents all that is best in New Zealand cricket. He becomes more determined and motivated when playing for his country. The excitement of Test cricket bring a new dimension to his game. He is able to concentrate on concentrating, as national pride lifts his performance. When questioned at the end of an innings that has helped his side to victory, the word “pride” usually figures in his phrases.

Coney made his first-class debut – for a New Zealand Under-23 XI against Auckland – when he was 18, a tall, gangling, youth who dressed as the flower-power children did at that time. His shoulder-length hair prevented him from being selected for Wellington in one age-group team. When he arrived in Australia as a replacement for an injured Glenn Turner in December 1973, his cricket gear consisted of a yellowing and heavily plastered bat, which bore the name of his club, Onslow, in large letters on the back.

The team manager, R.A. Vance, now chairman of the New Zealand Cricket Council, gave Coney some money and told him to go and buy a new bat. Some hours later Coney returned with a guitar and made do with other players’ cast-offs. His love of music is still with him and he frequently enlivens bus tours by playing his guitar. Today his hairstyle has changed markedly and his only problem with cricket clothing is that the trousers are not always long enough.

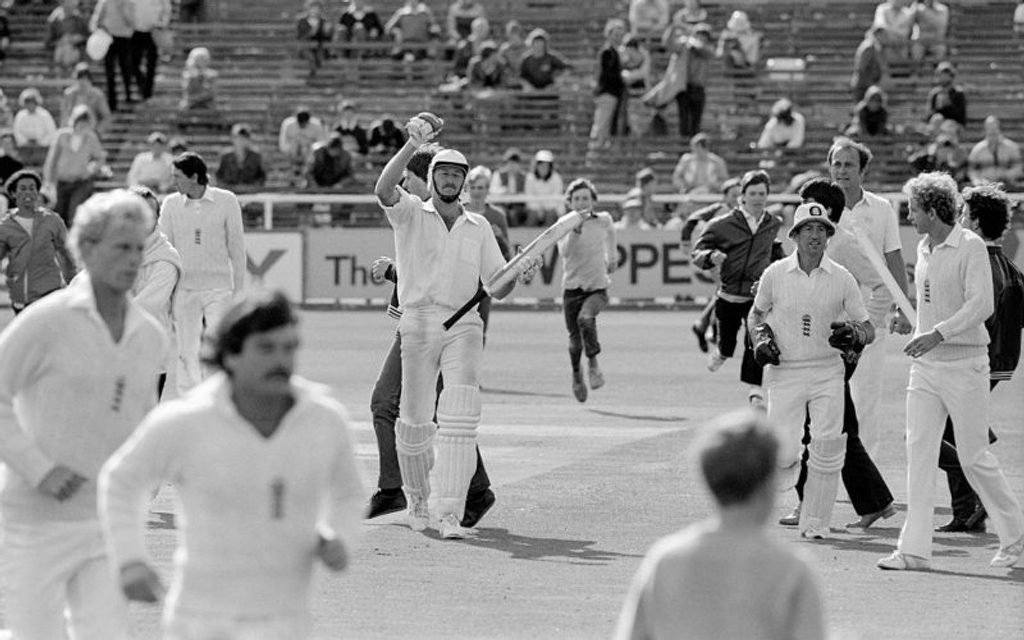

Jeremy Coney celebrates New Zealand’s first ever Test win on England soil, at Headingley in 1983

Jeremy Coney celebrates New Zealand’s first ever Test win on England soil, at Headingley in 1983

Coney made his mark in his first Test when he scored 45 against Australia at Sydney. He stood firm against an Australian attack for 135 minutes with a composure which belied his 21 years and relative inexperience. He also held three catches at slip in Australia’s first innings. Throughout his career he has possessed sharp hands and been an asset in the slips.

In his apprenticeship years Coney played to stay in. Occupation of the crease was his prime objective. As his confidence has developed he has realised that a half-volley is a gift to be driven with widened shoulders and swirling bat, and he is now adept in driving in the classic, old-fashioned way wide of mid-on.

After a promising beginning, which included taking part in New Zealand’s first victory over Australia, Coney was in the wilderness for five years, emerging for the series against Pakistan in New Zealand in 1979, when Bevan Congdon, also a medium-paced all-rounder, retired. He made his return a striking one, scoring 6, 36, 69, 82 and 49 in his first five innings. It seemed as if the Test-match atmosphere gave an edge to his batting that was not always apparent when he was playing more mundane first-class matches.

This was the time when crowd involvement in cricket was coming to the fore in New Zealand. The louder the roar of the crowd the straighter Coney played. During this series against Pakistan, he utilised his skills learnt from volleyball to counter the rising deliveries of Imran Khan. To protect his ribs he leapt in the air to come down on the ball and eliminate catches to close-in fielders. The first few times he did it, patrons at the ground laughed, as did the Pakistanis; but by the end of the series critics were conscious that he had found a new way of handling lifting deliveries. Since then he has used the same technique to good effect, as against Bob Willis in England in 1983.

Jeremy Coney poses with The Cornhill Trophy at The Oval in 1986

Jeremy Coney poses with The Cornhill Trophy at The Oval in 1986

Throughout cricket history there have been quality batsmen who have had great difficulty in breaking the barrier imposed by scoring a Test century. By the end of New Zealand’s tour of England in 1983 Coney had played 42 Test innings and made ten half-centuries without going on to three figures. Bobby Simpson scored his first 100 for Australia only in his 30th Test.

When Coney made his debut for Wellington, in 1971/72, one-day cricket was just being introduced to New Zealand. He is now the product of having played the limited-overs game for all his career. From its outset he has benefited from the knack of successfully pacing a game towards the end of an innings. He is, however, a cricketer who is not going to appear high in the averages at the end of his career. Until statistics can indicate such factors as courage and refusal to surrender they will not adequately convey the mettle of such innings as Coney played in 1983 in the Prudential World Cup.

At Edgbaston, chasing 235, New Zealand were in trouble against England when Willis quickly disposed of Turner and Edgar. Coney shared partnerships of 71 with Howarth and 70 with Hadlee which took New Zealand close to victory. Keeping calm in the eye of the storm he was 66 not out when the winning run was struck off the penultimate ball.

In the last few seasons Coney has gained a reputation for being New Zealand’s bits and pieces man. On the third day of the first Test in England last year, when England sought quick runs, Coney bowled 27 overs of seemingly innocuous medium-pace and conceded only 39 runs. His bowling also played a vital part in New Zealand’s historic victory in the second Test at Headingley. When England batted a second time, 152 runs in arrears, Coney bowled Lamb for 28 and had Botham caught soon afterwards.

To spectators in New Zealand, Coney is in some ways a mystery. Until the last few seasons his cricket record was more promising than impressive. Now, after several spine-tingling finishes, his efforts have brought recognition as well as success. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he regards international cricket as an experience unparalleled in joy and excitement.