Jack Gregory was, in partnership with Ted McDonald, one of Australia’s most destructive fast bowlers. His Wisden obituary in 1974 celebrated an explosive talent.

Gregory, Jack Morrison died on August 7, 1973, aged 77.

Jack Morrison Gregory, of a famous Australian cricket family, had a comparatively brief Test match career, for although he played in 24 representative games, his skill and his power were as unpredictable as a thunderstorm or a nuclear explosion. He was known mainly as a fearsome right-arm fast bowler but, also, in Test matches he scored 1,146 runs, averaging 36.96 with two centuries. He batted left-handed and gloveless.

As a fast bowler, people of today who never saw him will get a fair idea of his presence and method if they have seen Wes Hall, the West Indian. Gregory, a giant of superb physique, ran some 20 yards to release the ball with a high step at gallop, then, at the moment of delivery, a huge leap, a great wave of energy breaking at the crest, and a follow-through nearly to the batsman’s door-step.

He lacked the silent rhythmic motion over the earth of EA (Ted) McDonald, his colleague in destruction. Gregory bowled as though against a gale of wind. It was as though he willed himself to bowl fast, at the risk of muscular dislocation. Alas, he did suffer physical dislocation, at Brisbane, in November 1928, putting an end to his active cricket when his age was 33.

My earliest vivid impression of his fast bowling was at the beginning of the first game of the England v Australia rubber, at Trent Bridge, in 1921. The England XI had just returned from Australia after losing five Tests out of five (all played to a finish). Now, in 1921, England lost the first three encounters, taking long to recover from Gregory’s onslaught at Trent Bridge.

He knocked out Ernest Tyldesley in the second innings with a bouncer which sped from cranium to stumps. Ernest’s more famous brother J. T. had no sympathy; he bluntly told his brother, “Get to the off side of the ball whenever you hook, then, if you miss it, it passes harmlessly over the left shoulder.” At Trent Bridge, that May morning in 1921, “Patsy” Hendren arrived with runs in plenty to his credit, largesse of runs in county matches. Gregory wrecked his wicket with an atom bomb of a breakback. Yes; it was a ball which came back at horrific velocity, not achieved, of course, by finger-spin, but by action.

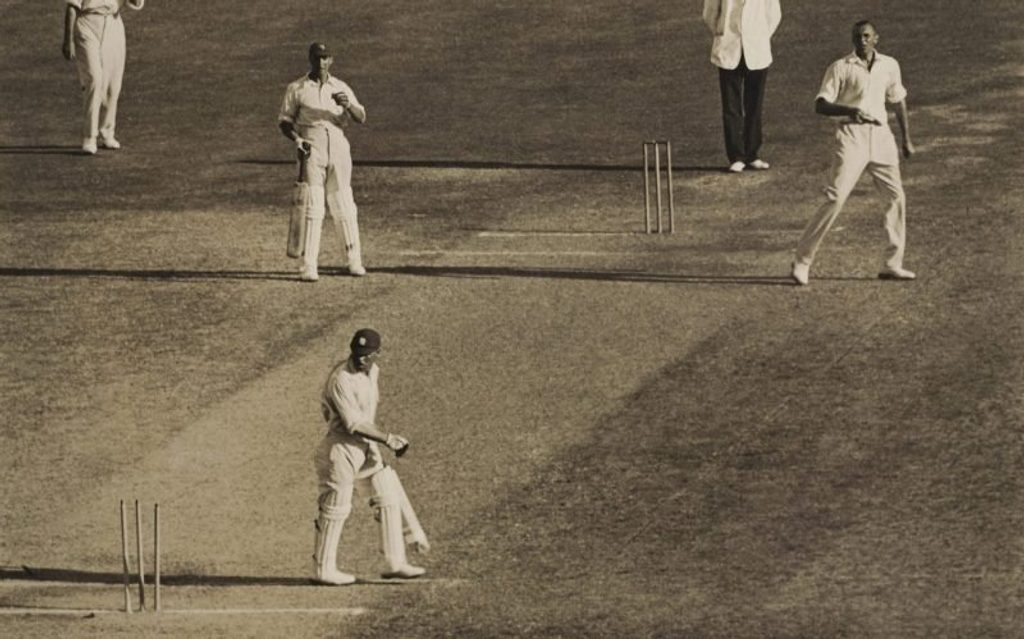

England’s Patsy Hendren is knocked over by Jack Gregory at the MCG, circa 1925

England’s Patsy Hendren is knocked over by Jack Gregory at the MCG, circa 1925

Gregory, like Tom Richardson, perhaps the greatest of all fast bowlers ever, flung the upper part of his body over the front left leg to the offside as the arm came over, the fingers sweeping under the ball. Herbert Strudwick once told me that in the first over or two he took from Richardson he moved to the offside to “take” the ball. It broke back, shaving the leg stump, and went for four byes. Gregory, at Trent Bridge, took six wickets for 58, in England’s first innings of 112; next innings McDonald took five for 52. Only once, at Lord’s, in 1921, did Gregory recapture the Trent Bridge explosive rapture.

In the South African summer of 1921/22 he renewed his batteries and regained combustion. Next, in Australia 1924/25, he was able to take 22 wickets in the Tests against England at 37.09 runs each. But the giant was already casting a shadow; in 1926, in England, his three Test wickets cost him 298 runs. He was not a subtle fast bowler, with the beautiful changes of pace, nuance and rhythmical deceptions of Lindwall or McDonald (at his best). But as an announcement of young dynamic physical power and gusto for life and fast bowling, there has seldom been seen on any cricket field a cricketer as exciting as Jack Gregory.

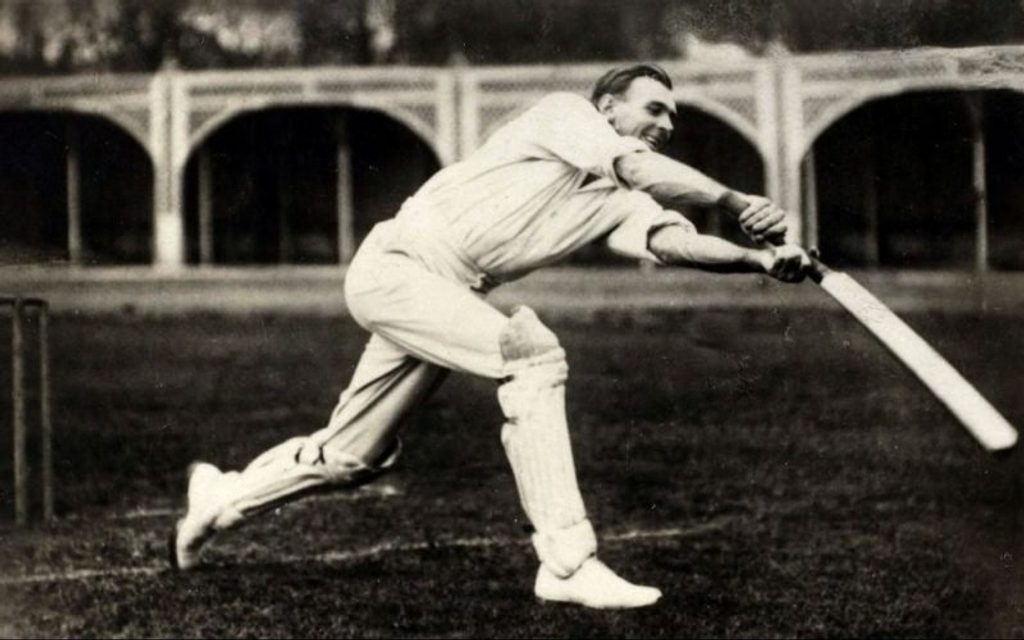

Jack Gregory batted gloveless

Jack Gregory batted gloveless

In 1921 certain English critics made too much ungenerous palaver about Gregory’s “bouncers”. These “bouncers”, no doubt, were awesome but not let loose with the regularity of, say, a Hall, a Griffith, not to mention other names, some playing today. In fact, no less an acute judge of the game as A.C. MacLaren declared, in 1921, that Gregory’s bowling during the first deadly half hour at Trent Bridge was compact of half-volleys.

His baptism in English cricket was in 1919, with the Australian Imperial Forces team. He was already a menacing shattering fast bowler, but at Kennington Oval he was subjected to treatment such as he never afterwards had to suffer. Surrey faced a total of 436 and got into hopeless trouble. They wanted 287 to save the follow-on and five wickets went down for 26. Soon J. N. Crawford came in at No.8 – a catastrophic moment – and he smote Goliath.

He smote Gregory as any fast bowler has not often been smitten, except by Bradman and Dexter. Crawford actually drove a ball from Gregory, that immortal afternoon at Kennington Oval, into the pavilion, cracking and splintering his bat. When Rushby, the last man, went in Surrey still required 45 to save the follow-on. Crawford went on hitting magnificently and they added 80 in 35 minutes, Rushby’s share being a modest two. In some two hours Crawford scored 144 not out having hit two sixes and 18 fours. And Gregory applauded him generously.

He was a generous and likeable Australian. He gave himself to cricket with enthusiasm and relish. He enjoyed himself and was the cause of enjoyment in others. At Johannesburg in 1921, Gregory scored a century in 70 minutes v South Africa – the fastest hundred in the long history of Test cricket. He was a slip fielder of quite an unfair reach and alacrity, a Wally Hammond in enlargement, so to say, though not as graceful, effortless, and terpsichorean. Gregory was young manhood in excelsis. All who ever saw him and met him will remember and cherish him.