Ian Chappell ended his reign as Australia captain in a blaze of runs in 1975. The following year, he was named a Wisden Cricketer of the Year.

Ian Chappell played his last Test for Australia in 1980, and retired with 5,345 runs at 42.42 in 75 matches.

Australian cricket was going through a disastrous period when Ian Michael Chappell was thrust into the captaincy in the final Test of the 1970/71 series against England. He lost his first Test by 62 runs, his second 89 runs and then was never beaten in a Test series against any country.

When Chappell took over, the national team had not won a Test in the previous nine times of asking. To make room for him at the top, the Australian selectors removed WM Lawry in a step that had all the subtlety of the guillotine in the French Revolution. Not only was Lawry dropped from the captaincy but from the team as well, at a time when he had made 324 runs, average 40.50 against Snow and company.

An unjust reward perhaps for a man who made over 5,000 runs for Australia and often had to make do with a bowling attack better recognised for its fighting heart than any ability to blast out the opposition. Any Test team needs two top-class bowlers to win a series. Three is a wonderful bonus. When Chappell took over as captain the bowling attack was an inexperienced Lillee, Dell from Queensland, Walters, GS Chappell, Jenner and O’Keeffe. It was not until the second Test in England at Lord’s in 1972 that the Lillee-Massie combination came together and they squared the series there, with Massie making a dream debut in Test cricket.

Back in Australia two names were on the selectors’ short list for the future; JR Thomson and MHN Walker, the first an unorthodox but very fast bowler and the second a promising medium pacer. It was on those two, plus Lillee and the reliable Ashley Mallett, that Chappell based his on-the-field strategy and Australia have not had many better combinations over the years with the ball, particularly when allied to the brilliant close-to-the-wicket catching produced by the team.

The fast bowlers’ skills were blunted a little by the dry summer in England in 1975 but Chappell still won that series and, in the final Test at The Oval, announced his decision not to be available again to captain Australia.

Chappell captained Australia 30 times, won 15 of those games and lost only five, two of the latter being his first two efforts. By the time he retired from the leadership to be a Test player only, he had lifted Australia right back to the top in world cricket. His brother Greg took over the captaincy and celebrated his appointment by becoming only the fourth Australian to hit a century in his first innings as skipper – 123 against the West Indies in Brisbane.

Ian left him a legacy of a very good cricket team with a wonderful team spirit and a burning ambition to stay on top. He did more than that, however, for his players. Ian Chappell is and was very definitely a players’ man. He has had more brushes with officialdom than any other player since KR Miller and SG Barnes just after the end of the war and most of those brushes have been because of his unwillingness to compromise.

Nothing is a shade of grey to Chappell and, although his candid speech and honesty can be refreshing, the same attributes also have landed him in trouble with administrators on several occasions. In the summer of 1975 in Australia he was carpeted by the South Australian Cricket Association, and warned that a recurrence of complaints from umpires concerning the bowling of protest head-high full tosses, and further excessive use of bad language on the field, would bring suspension.

Three weeks later in Brisbane he wore Adidas cricket boots with three blue stripes instead of the three white stripes, and was warned of the Australian Cricket Board’s insistence on white gear being worn on the field. Chappell’s reply appeared in an Australian newspaper the next day, wherein he said he supposed if he wanted to play in the remaining Tests in the series against the West Indies he had better put his boots back in the cupboard.

#OnThisDay in the 1948 Lord’s Test, Keith Miller refused to bowl when asked to by Don Bradman, having told him pre-Test that a back injury meant he could only play as a specialist batsman.

According to Ian Chappell, it took the Don a while to let it go…https://t.co/FH5WJMPtfP

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) June 25, 2020

He also made some typically candid and accurate remarks about the administrators’ attitudes to advertising on Test match ground fences, and advertising used by players.

By his players and others of the same era, Chappell will be remembered as much for his bid to improve the players’ lot as he will for his run-getting and captaincy. He became the first captain to be invited to the Australian Cricket Board’s annual meeting, where he put up several suggestions to the Board concerning possible improvements for players and changes in the Laws.

He was instrumental from the team’s point of view in negotiating the bonus from the 1974/75 series, and there followed an increase in players’ payments and allowances. The Australian Cricket Board contains many youngish administrators nowadays, and they too have been keen to see that the players are looked after as well as possible.

Chappell himself would disclaim any suggestion of militant shop-steward style thinking, but he has certainly livened things up in four years of captaincy, in a game where the top players have always been ridiculously underpaid.

At the same time, he has batted brilliantly for Australia on many occasions and is approaching 5,000 runs in Tests. The man he succeeded as captain, WM Lawry, classes him as Australia’s best player on all types of pitches, a rating that is disputed by those who see his brother Greg as one of the great players for Australia since the war. As batsmen they are different types, as different as they are in personality. Greg is the more elegant strokeplayer of the pair, Ian the more rugged and ebullient in his shot-making.

Ian was born on September 26, 1943 at Unley, South Australia and played first for South Australia against Tasmania in the 1961/62 season, hit a splendid century against New South Wales a little later and played in the only Test against Pakistan in Melbourne in 1964. In 1965/66 in Australia, he played in the final two Tests when Australia squared the series, but his Test batting results were moderate until he played against India in Melbourne in December 1967 and hit a magnificent 151 against an attack based on spin.

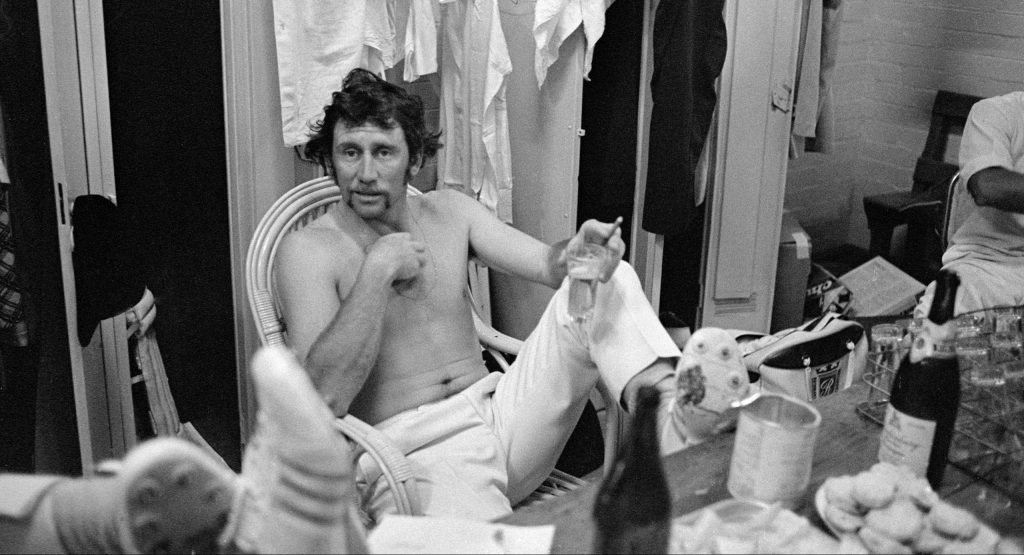

Ian Chappell was outspoken, and that meant the authorities had a hard time dealing with him

Ian Chappell was outspoken, and that meant the authorities had a hard time dealing with him

In 1968 in England, he finished second in the Test averages to Lawry, averaging 43 for 348 runs, and he topped the tour batting figures with 1,261 runs at 48.50 per innings – IR Redpath was the only other batsman to reach 1,000 runs for the tour. After being made captain he played some splendid fighting innings for Australia, notably in the opening Test in Brisbane in 1975 when, on a pitch of decidedly variable bounce, he made 90 and allowed Australia to finish with a first innings score of 309. In England in 1975, he had a great series, scoring 429 runs at 71.50 and making 192 at The Oval, as well as three other half centuries.

He has been a most reliable No.3 for his country – never backward in taking on the fast bowlers with the hook shot, though in recent times he has been more careful to pull in front of square leg rather than hook in the area behind the umpire. His batting technique has been carefully planned to provide the best possible returns against pace bowling and he is always concentrating on getting behind the line of the ball, too much so on occasions when England’s fast bowlers have been able to take advantage of a sight of the leg stump.

He hit a century in his final match as captain of Australia, and his brother Greg, who was one of the Wisden Five in 1973, hit a century in his first Test as Australian captain. A unique record. The statistics will not unduly delight Ian … he is interested more in winning cricket matches than the figures produced by those who do the winning.