Harold Larwood, the fearsome spearhead of England’s Bodyline attack, died on July 22, 1995. His Wisden obituary revisited one of the most turbulent episodes in cricket history.

Larwood, Harold, MBE, died on July 22, 1995, aged 90.

Harold Larwood was one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time. But this will forever be overshadowed by his role in the cricketing controversy of the century, the Bodyline Affair. It is a dispute that retains its extraordinary potency even though nearly all the participants are now dead. It came close to rupturing cricket; indeed, it might have ruptured relations between Britain and Australia. But it was in the nature of cricket that Larwood should eventually settle happily in Australia, the country whose batsmen he once haunted.

Harold Larwood was a miner’s son from Nuncargate outside Nottingham. He left school at 13; at 14 he was working with the pit ponies at Annesley Colliery near Nottingham and would doubtless have become a miner himself had he not already been showing promise at cricket; at 18 he had a trial at Trent Bridge. This was the classic instance of a county whistling down the nearest coal mine when they wanted a fast bowler.

In 1924, at 19, Larwood was starring in the second XI and making his Nottinghamshire debut; in 1925 he was a first-team regular; in 1926 he was in the England team at Lord’s and, more significantly, the one that regained the Ashes at The Oval. In that match he took six wickets, all front-line batsmen, and consistently troubled everyone with pace and lift from short of a length.

The word was already going around that ‘Lol’ Larwood was the quickest bowler seen in years. In 1927 he came top of the national averages. By 1928 he was in harness with the left-armer Bill Voce and together they would become the world’s most feared pair of opening bowlers.

England cricket captain Douglas Jardine presents certificates to Larwood and Bill Voce in 1938

England cricket captain Douglas Jardine presents certificates to Larwood and Bill Voce in 1938

Larwood began the 1928-29 series in Australia with a match-winning six for 32 on the old Exhibition Ground in Brisbane (in addition to scoring 70). The only batsman in the top seven that he did not get out in that match was the debutant D. G. Bradman and, though England comfortably retained the Ashes, Bradman asserted his authority as the series progressed. By the time he came to England in 1930, he was almost unassailable.

Larwood played only three of the Tests that summer, and took just four wickets. Australia regained the Ashes. The combination of shirt-front wickets and the greatest batsman of all time was enough to break the spirit of any bowler. Larwood’s urge to find something, anything, that would enable him to defeat Bradman, was crucial in rendering him a willing instrument in the crisis that was to come.

Bodyline, or leg-theory bowling, with bowlers aiming at the body with a ring of predatory leg-side fielders, was not unknown at this stage; Arthur Carr, the Nottinghamshire captain, would sometimes unleash Larwood in that manner in county matches. Several batsmen were carried off unconscious after being hit by Larwood even when he was bowling normally.

Carr used Bodyline as a tactic. Douglas Jardine, who led England in Australia in 1932-33, elevated it into a strategy. But Larwood was not just his dupe. “The game had become so biased in favour of the batsmen, there was no pressure on them at all,” he said in 1983. “If we got four wickets down in a day, we’d done a good day’s work. If we got five we had an extra drink. Our way was the only way to quieten Bradman. I knew that if we eased up, we’d have to pay for it.”

The controversy reached boiling point in the Adelaide Test when Larwood hit Bill Woodfull over the heart and Bert Oldfield over the temple. “Larwood again the unlucky bowler”, as the newsreel commentator famously said. It was the feeling that Larwood, far from being unlucky, had achieved his side’s objectives by inflicting injury that incensed the Australians. However, when he made 98 as a nightwatchman in the final Test in Sydney he was, according to Wisden, “loudly cheered”.

Larwood damaged his foot while bowling in that match, though Jardine made him stay on the field until Bradman was out. The foot injury meant he could bowl only ten overs in the 1933 season, and by the time the Australians came to England in 1934 the full implications of Bodyline had sunk in.

A combination of poor communications, inadequate newspaper coverage and imperial arrogance, especially at Lord’s, had prevented English cricket understanding immediately what had been going on in Australia. But once opinion had changed, Larwood is understood to have been given a letter of apology and told to sign. He refused and never played another Test match, alienating MCC once and for all by giving frank opinions on the subject to the Sunday Express.

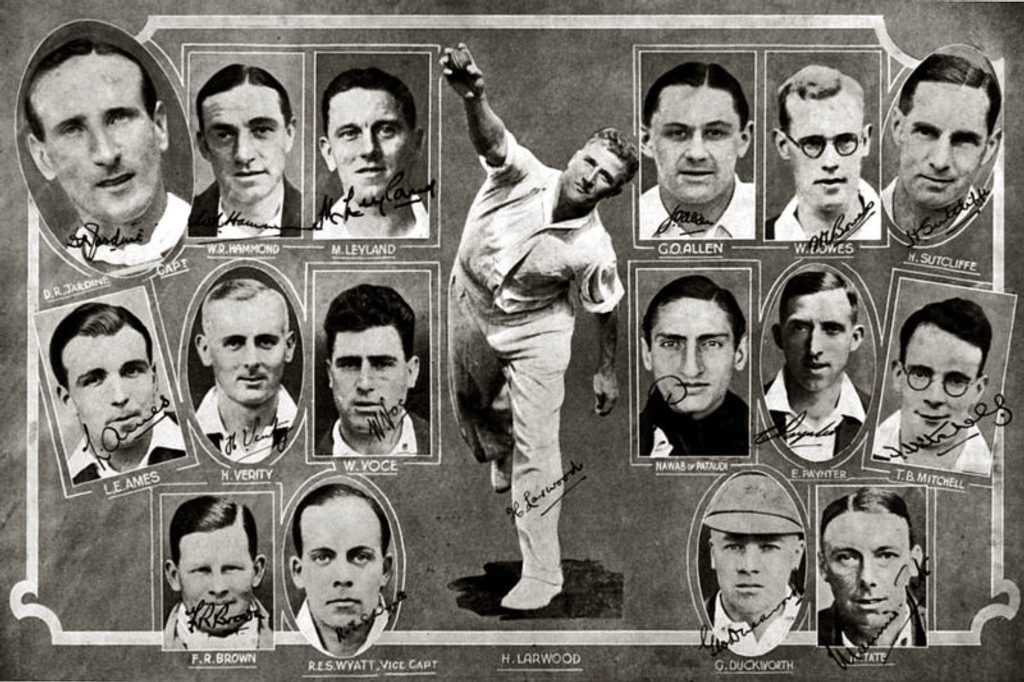

The England team which brought back “The Ashes” from Australia after winning the Test series 4-1 in 1933

The England team which brought back “The Ashes” from Australia after winning the Test series 4-1 in 1933

At the time he paid the penalty rather than Jardine, who captained MCC again in India in 1933-34. History has reversed the judgment, and Jardine is usually painted as the villain. Larwood’s loyalty to his skipper remained unshaken until he died.

He continued to play county cricket to devastating effect and topped the national averages for the fifth time in 1936, two years before he finally retired. Bodyline had almost disappeared after Jardine’s tour and was formally outlawed two years later. Larwood, though, was good enough, even if he was slowing down, to achieve success without it.

He was only about 5ft 8in, less than 11 stone, and his training regime seemed to consist largely of beer and cigarettes. But he was stocky, and his technique was magnificent: “He ran in to bowl with a splendid stride,” wrote Neville Cardus, “a gallop, and at the moment of delivery his action was absolutely classical, left side showing down the wicket, before the arm swung over with a thrillingly vehement rhythm.”

Later generations, observing only a few newsreel clips, have wondered whether Larwood threw; contemporary critics echoed the Cardus line – and in any case his Australian victims might just have raised the subject if there was any doubt at all.

His bouncer was truly terrifying to unprotected batsmen, but it was employed only sparingly for most of his career. Of his 1,427 first-class wickets, more than half – 743 – were bowled. Larwood’s average was 17.51, which was outstanding in a batsman’s era; in his 21 Tests he took 78 at 28.35. His batting average was close to 20, and he scored three centuries.

After retirement, Larwood settled in an obscure Sydney suburb

After retirement, Larwood settled in an obscure Sydney suburb

After retirement, he went into eclipse and was living in Blackpool with his wife and five daughters, running a sweet shop, when he decided to emigrate to Australia. In 1949, he sailed on the Orontes, the ship which had taken him there, more famously, 17 years earlier. Encouraged by a former opponent, Jack Fingleton, and helped by a former Australian prime minister, Ben Chifley, Larwood settled in an obscure Sydney suburb, got a job on the Pepsi-Cola production line, and worked his way up – “not because I was a cricketer but because I could do the job” – to managing the lorry fleet.

It was possible to hear the noise of the Sydney Cricket Ground from his bungalow when the wind was right, and it became a place of pilgrimage for visiting Englishmen with a sense of history; Darren Gough delighted the old man by calling there in 1994-95. By then Larwood was blind, and long before that visitors were baffled by the idea that this shy, stooped, kindly man could ever have terrorised cricket.

There was never a hint of animosity in Australia, and Larwood had no regrets either, although he repented of his old view that Bradman was frightened of him. “I realise now he was working out ways of combating me.” John Major signalled the British Establishment’s forgiveness by awarding him the MBE in 1993. Larwood was most proud of the ashtray given him by Jardine: “To Harold for the Ashes – 1932-33 – From a grateful Skipper.”

Read more Almanack articles