Graham Gooch, who celebrates his birthday on July 23, did not have a smooth path to the England captaincy, but once he got the job he revolutionised the team’s approach. After his record-breaking summer of 1990, Wisden published this assessment in 1991.

Ian Botham has, in his time, managed to make a fair amount of trouble for himself. But not even Botham managed to get himself banned from Test cricket for three years, or made himself the hate-focus of an international political campaign, or caused an entire tour to be cancelled. Graham Gooch has done all those things. How extraordinary then, how absolutely extraordinary, to consider that this is the man we must begin to think of as the most important cricketer of his generation, and the most effective captain of England since Mike Brearley.

Yes, Gooch said famously, we’ve got the makings of a goodish side. The point is that this was not an understatement: it was an exact assessment of the facts. Gooch’s achievement has been to maximise the resources of that goodish side. It has been a triumph of nothing less than leadership, and this from a man who resigned as captain of Essex because captaincy was affecting his form.

Graham Gooch, 1981

Graham Gooch, 1981

It is clear that captaincy affected his form as captain of England in the summer of 1990. To be accurate, captaincy inspired him. It took him to the enormous achievement of his innings of 333 against India at Lord’s, and his breaking of Sir Donald Bradman’s record for Test runs scored in an English summer.

Gooch had always been a man in search of greatness; he achieved that immodest aim last summer. He achieved greatness as a player – at the age of 37. Such preposterous scores are normally for younger men. The fitness, the reflexes, the ability to concentrate for session after session: these are things that the years take away from you. But they have not taken them from Gooch. Gooch is a fanatic for mere fitness, a passionate lover of work for its own sake, a true glutton for austerity. Furthermore, he has achieved something quite close to greatness as a leader. Before he was given the captaincy, England’s cricket had become the material of cheap jokes: material the more discriminating joke-crackers avoided. A quip about England’s defeats was simply too obvious, too hoary a joke.

The joke reached its apex in 1988, “the summer of the five captains”. This was perhaps the most inept display of man-management in the history of sport; a summer in which Gatting, Emburey, Cowdrey, Gooch himself and Pringle all led England in the field, four of them as official appointees. When Gooch was asked to lead England in India, the tour was promptly cancelled because of Gooch’s South African connections. Disaster followed disaster. After the West Indian hammering and the Indian debacle, there came another traumatic summer. The opponents were Australia. England, captained now by Gower, were not only beaten but trampled on.

For Gooch, as for Gower, the summer was a personal disaster. There was scarcely a scoreboard, it seemed, that did not carry details of Gooch lbw b Alderman, for not a lot. Gooch volunteered to stand down, to make room for fresh blood, and his offer was accepted. Perhaps that one incident summed up his summer: a personal nadir, a personal black hole. For some cricketers it would have been a disaster of career-ending proportions. Instead, Gooch used it as a springboard into greatness.

“There was scarcely a scoreboard, it seemed, that did not carry details of Gooch lbw b Alderman, for not a lot”

“There was scarcely a scoreboard, it seemed, that did not carry details of Gooch lbw b Alderman, for not a lot”

There is a case for saying that Headingley 1981 is one of the greatest disasters to have hit England’s cricket. Certainly, it lunged into a pattern of self-destructiveness as the echoes of that extraordinary year died away. The England team became based around an Inner Ring, with Botham at its heart: Botham, self-justified by his prodigious feats during that unforgettable summer. To be accepted, you had to hate the press, hate practice, enjoy a few beers and what have you, and generally be one hell of a good ol’ boy. Like all cliques, the England clique was defined by exclusion. Nothing could be more destructive to team spirit than a team within a team, but that was the situation in the England camp for years. It was the same at Somerset. It was the presence of an Inner Ring which created the furore in which Vivian Richards and Joel Garner were not offered new contracts, and Botham himself resigned.

It needed the right man at the right time to destroy this unpleasant and destructive atmosphere in the England team. The old members of the Inner Ring were being lost to time, one by one. It needed someone to indicate that it was gone forever; that this was a new start, a new way forward. This was Gooch’s moment, and he accepted it avidly.

It happened in India in the autumn of 1989. India had rejected an England team under Gooch’s captaincy a year before. Now they accepted one. The Test-playing countries had at last come to an agreement about players with South African histories. Gooch was officially forgiven. The way was clear for the remaking of the England cricket team. The tour itself, a four-week trip for the Nehru Cup, a six-nation one-day tournament, was thought by all wise critics to be a complete waste of time. The widely used mot juste for the competition was “spurious”. It was not spurious at all for Gooch.

It was on a practice ground in Delhi that one became aware of strong forces at work. The weather was hot, but the pace of the practice was still hotter. It was all sweat and Gatorade: everyone was competing as to who sweated the most. Micky Stewart, the manager, was like a man come into his own, taking fielding practice with all the camp affectations of a sergeant-major. It looked as if Stewart was having his way at last, but he was not. Gooch was. The two of them plainly saw eye to eye; not something that had always been the case with Stewart and his captains. They were dubbed “the Cockney Mafia” almost within hours.

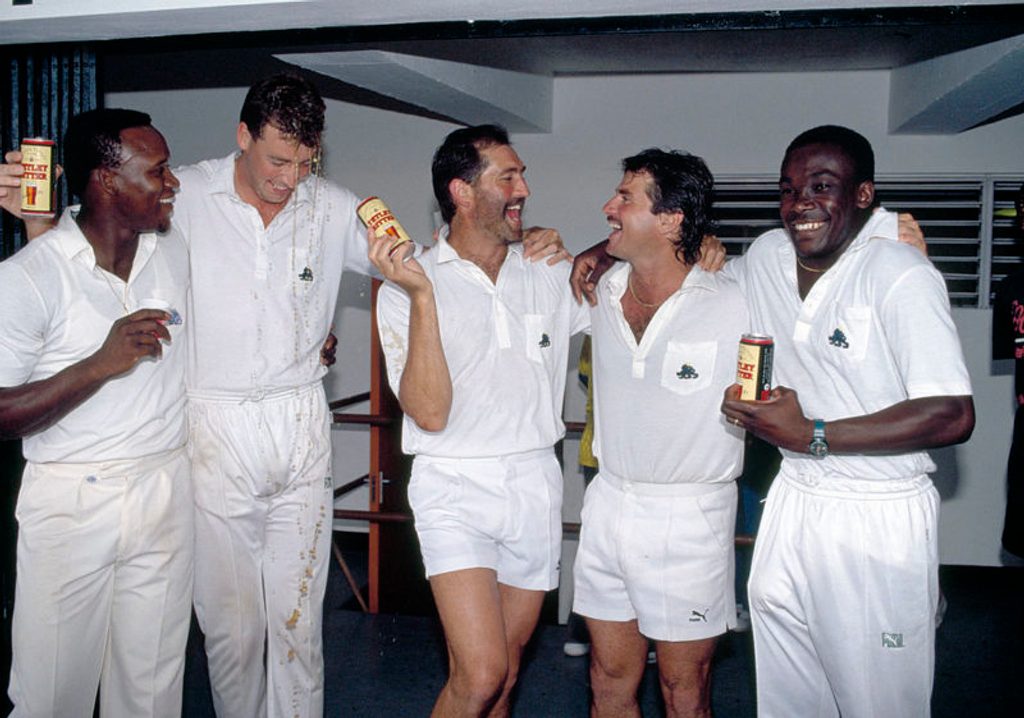

Gooch (middle) with his teammates after England’s win over West Indies at Sabina Park, March 1990

Gooch (middle) with his teammates after England’s win over West Indies at Sabina Park, March 1990

That has been his miracle. The results in the West Indies in the early months of 1990 did not surprise him. It was only everybody else who was surprised by the win and the near-win under his captaincy. Gooch would, I think, have escaped from the series on level terms at worst, had it not been for the injuries to himself and to Angus Fraser. Instead, England lost 2-1. The two 1-0 wins in the following summer’s three-Test series against New Zealand and India were consolidation. Suddenly, England had acquired the habit of winning Test matches. That was miracle enough to be going on with.

The central experience of Gooch’s professional life was his trip to South Africa in 1982. He went to play on that “rebel” tour in the hopelessly naive belief that he would not receive any form of punishment. He was made captain of the rebel team, though not as a recognition of any leading part in the plotting and deception involved in the setting-up of this tour: it was more an expression of the dressing room’s feelings about having Geoffrey Boycott as captain. But the responsibilities of the captaincy were not restricted to cricketing decisions. Gooch did not expect that. The captaincy made Gooch the spokesman of the tour. “Gooch’s men” and “Gooch’s rebel tour” were phrases that tripped nicely off page and microphone. Gooch himself had to face cameras and interviews: this was, as far as the Republic was concerned, a major public-relations exercise. These were muddy waters, and Gooch hid behind his role of professional sportsman. “We’re just here to play cricket, we’re just professional cricketers.” Would that life were as simple.

Gooch and his fellow-rebels were banned from Test cricket for three years. I am sure he still feels that this was desperately unjust; I suspect that even now, he finds this “wrong” an inspiration. For whereas many of his colleagues on that South African venture were well-known players slightly over the hill, Gooch was in his prime. His adventures robbed him of three years in which he might have established himself as the greatest batsman of his generation. Instead, he played for Essex and Western Province. Still, his career has been characterised as much by its troughs as by its peaks. He began his Test career with a pair in 1975; he chose not to tour Australia in 1986-87 because his wife, Brenda, was pregnant with twins; and Terry Alderman has turned up to blight his life more than once or twice. He even began his annus mirabilis of 1990 with a “king duck” against New Zealand.

Perhaps Gooch’s greatest asset of all has been his ability to give equal treatment to Kipling’s twin imposters, Triumph and Disaster. He remains consistent in everything in his life except shaving. His capricious changes from a clean shave, Zapata moustache, designer stubble or full beard have been the nearest he has come to a change of facial expression in 15 years. But he is not an easy person. He does not forget those who, he believes, have done wrong by him. He has no appreciation of the necessary symbiosis of professional sport and mass media. His achievement in cutting down the number of compulsory captain’s press conferences during a home Test from three to one was regarded as a major coup.

Gooch on his way to 333 against India, July 1990

Gooch on his way to 333 against India, July 1990

The chairman of the England selectors, Ted Dexter, when in his journalistic avatar, famously described Gooch as having the charisma of a wet fish. This has been thrown back at Dexter times without number, but it is, in fact, a fair remark – from a media person. All the same, Gooch cannot have achieved his success without great gifts of communication. It just so happens that these gifts are not apparent to those outside the charmed circle of his team. Nor does his team find Gooch’s gifts readily communicable to the outside world. The nearest anyone ever gets to an explanation is to say that he leads “by example”. But this means little. Plenty of leaders have worked themselves silly while inspiring only contempt. Gooch simply has, at a point that must be alarmingly close to the end of his cricketing life, come into his own. He has reconstructed and re-inspired the England cricket team: and it seems that he has done a similar job on himself. Yet he remains as hostile to outsiders as ever, and the team is probably even less approachable now than it was in Botham’s time. There is still an Inner Ring: the difference is that Gooch appears to have made everyone in the team a member of it.

Right from the first moment that he took charge in Delhi, Gooch made it clear that he wanted only to be judged on results. In those terms, he has established himself as a truly great cricketer. His achievement in remaking the England team might yet be even more significant, and in this much larger area he again bears the stamp of incipient greatness.