Garry Sobers celebrates his birthday on July 28. When he was one of Wisden’s five Cricketers of the Century in 2000, the Almanack asked a sportswriting heavyweight to provide a tribute.

Born to frugality and early tragedy in a one-storey wooden house on July 28, 1936, Garry Sobers seemed an unlikely candidate to become an icon at anything outside the parish of St Michael in Barbados. He was one of seven children, one of whom died in an accident with a kerosene lamp. Then, when he was five, a telegram arrived saying his father, a merchant seaman, had drowned with all hands when his ship was torpedoed by a U-Boat in the Atlantic. His mother, a strong Christian woman, heroically kept the family intact. Her pension was insulting. At 14, hardly an academic, he was a gopher in a furniture factory.

In February 1975, already celebrated as a face on Barbadian postage stamps, Sir Garfield St Aubrun Sobers was knighted by the Queen at the Barbados Garrison Racecourse, barely a mile down the road from where he was born in Walcott Avenue. It was not quite the ultimate accolade. In 1988, Sir Donald Bradman conferred on Sobers the title of the greatest all-round cricketer he had ever seen. Bradman’s judgment in these matters is regarded as Holy Writ.

Sobers averaged 57.78 with the bat in Test cricket

Sobers averaged 57.78 with the bat in Test cricket

None would contest it. Across two decades Sobers brought to a cricket world as diverse as the Caribbean, the Test arena, English county cricket with Nottinghamshire, Sheffield Shield cricket with South Australia, and even North Staffs and South Cheshire League cricket with Norton, plus hundreds of charity games, a vibrancy, nobility of spirit and versatility of accomplishment that transcended all statistics.

These were remarkable enough: 8,032 runs, 235 wickets and 109 catches in 93 Test matches for West Indies. More significantly, he could turn the tide of a Test within an hour, and it was on these occasions that partisanship was suspended. You simply sat back and marvelled at the occasion. From the direst situation his only thought was to attack. He was physically fearless. He never wore a thigh-pad, never mind a helmet, and, from his boyhood days with the Barbados Police team until his retirement, he was only seriously hit twice. Such was his adaptability that he could bowl left-arm very fast, swinging it both ways, left-arm finger-spin and left-arm wrist-spin. By his own recollection, he was no-balled fewer than half a dozen times during his entire career.

His real apprenticeship started at the age of 12 when, as the kid next door, he started bowling in the nets to members of the fashionable Wanderers Club, earning a 50-cent piece every time he knocked it off the centre stump. It made him more money than he earned at the furniture factory down the road. At 16, he was playing for Barbados against the touring Indians and taking seven wickets. At 17, he played his first Test for West Indies. At 21, against Pakistan in Jamaica, he broke Len Hutton’s Test record with 365 not out.

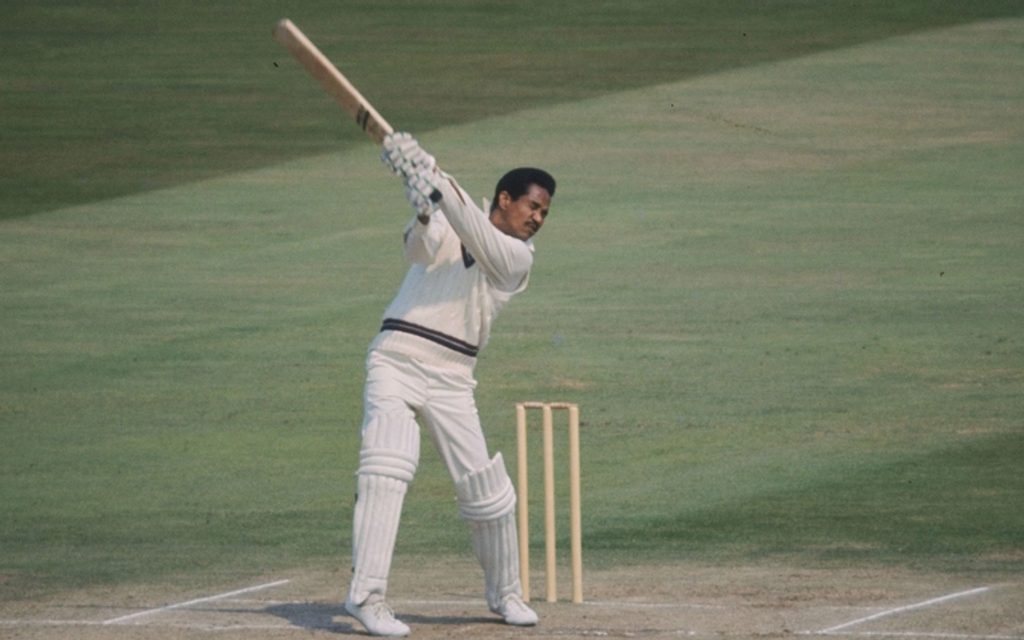

By now the world was acquainted with the kid from Walcott Avenue. He was an instinctive back-foot player, attacking with the lightest of bats (2lb 4oz) which frequently slapped his buttocks on the follow-through. Then he would bowl, crouched for wrist-spin, back arched for finger-spin, lithe as a panther when bowling fast. There was never a moment on a cricket field when you could take your eyes off him.

In 1971-72, Sobers led a World XI to Australia. Watching him in Melbourne, Bradman saw him play a straight drive against Dennis Lillee which smashed into the sightscreen almost before Lillee had straightened up from his follow-through. Sobers scored 254 (after a first-innings duck). Bradman, no soft touch when it came to criticism, rated it the greatest innings he had ever seen on Australian soil.

Sobers speaks to Brian Lara during a Test match in 1994

Sobers speaks to Brian Lara during a Test match in 1994

There was a fourth dimension to Sobers. In fact there were several others, since he was not averse to a drink or a gamble, and had a pretty complicated domestic life. But on the Test cricket field, when he succeeded Frank Worrell as captain, he was the last Corinthian of a dying breed. He walked when he had nicked a catch to slip, without even bothering the umpire. He would not abide sledging. And, once to his own detriment, he would risk the result to entertain a crowd.

In Trinidad in 1967-68, against Colin Cowdrey’s England team, he became so frustrated by their go-slow tactics that he declared, setting England 215 to win at 78 an hour. His bowlers sent down 19 overs an hour. England won. I met him that evening in a bar down by the port. He was all alone, and next day the Caribbean press rated him alongside a war criminal. It was never war to him, which was part of his greatness.