Matthew Engel, a former editor of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack (1993–2000 and 2004–2007), took a trip down memory lane when he attended the 50th anniversary of the Professional Cricketers’ Association (PCA).

Matthew Engel began collecting cricketers’ autographs before the invention of the PCA, but gave up when he started reporting the game in 1972.

Long before the start of play, the autograph collectors were there in force outside the big marquee. These were not, I thought to myself, the dressing room johnnies of my era. Now the huntsmen were as old as their quarry. And then I realised. That’s precisely who they were: the boys of half a century ago, still following the hobby of their youth, politely accosting the ageing cricketers as they walked – often stiffly – from the car park to join their comrades.

It was day two of the Cheltenham Festival, the day the Professional Cricketers’ Association held their annual gathering – the national version of the counties’ old players’ lunches which have become a yearly fixture on the circuit. This reunion, however, was special: the 50th anniversary of the PCA, founded in 1967 when Fred Rumsey, then of Somerset, summoned a representative from each county to London.

Fred Rumsey speaks to David Gower after collecting his Lifetime Achievement Award, 2017 NatWest PCA Awards

Fred Rumsey speaks to David Gower after collecting his Lifetime Achievement Award, 2017 NatWest PCA Awards

The players met the leaders of the football equivalent, Jimmy Hill and Cliff Lloyd, and diffidently began to formulate and articulate their views on cricket’s future. Some at Lord’s thought it was the beginning of the end: a small-scale mutiny that might lead to insurrection.

Rumsey had been plotting for over a year. He would ask Somerset’s opponents if he could address their players; surprisingly, most agreed. Less surprisingly, Rumsey had received a phone call from Warwickshire’s Jack Bannister, one of the most energetic and lateral-thinking of players. Bannister was to hold every office in the association over the next three decades. He died in 2016.

But four of those present at that first meeting made it to Cheltenham, all still recognisable. Rumsey, as dominant and burly as in his youth; the others as smiley and slim as one remembers – Mike Smedley of Nottinghamshire, Eric Russell of Middlesex, Don Shepherd of Glamorgan.

PCA officers Jack Bannister and Peter Walker during the 1982 AGM

PCA officers Jack Bannister and Peter Walker during the 1982 AGM

Shep was a month short of 90, just behind Roy Booth of Worcestershire as senior man in the tent. He was a most improbable revolutionary: “I hardly knew what a union was, or anything.” And indeed he was the most uncomplaining of cricketers – more wickets than anyone who never played a Test, but a man who could still say: “I was a very lucky boy.” Yet he shared the general sense that cricketers were not treated fairly. So did Russell, who took the practical step of roping in Harold Goldblatt, an accountant whose clients included most of the Middlesex and Surrey teams, not that they had much money to count.

Goldblatt in turn brought in the lawyer Lawrie Doffman, and the infant body – then known as the Cricketers’ Association – had the back-up expertise it desperately needed. Goldblatt, rabbinically bearded, was an honoured guest at Cheltenham.

Rumsey identified three burning issues: money, health and registration. The last proved simple, because the traditional practice of imposing a year’s ban on players who wished to move counties turned out to be unlawful and had to be scrapped. Other issues took a little longer.

English cricketer Fred Rumsey, July 1964

English cricketer Fred Rumsey, July 1964

“It was a voice, that was all,” said David Graveney, whose uncle Tom was infamously banned for a year in 1961 after leaving Gloucestershire. “In the era when my father [Ken] and uncle played, there was no question of medical insurance, no pension.” In 1998, David became the PCA’s first full-time chief executive.

In the late 1990s, two cricketers suffered terrible off-field injuries. One, Winston Davis, a former West Indies and Northamptonshire fast bowler, had recently retired; the other, Yorkshire’s Jamie Hood, had barely started. Both were left as tetraplegics, and initially the system was not geared to help them. “The condition of both Winston and Jamie presented new challenges for the organisation,” said Graveney. “We didn’t have enough resources to make a meaningful difference. Over time we have been able to do a great deal.”

At Cheltenham, a smiling Davis steered into the tent in his wheelchair, having organised the trip on his specially adapted computer and travelled to the ground in his specially adapted vehicle, both provided by the PCA. Hood was not there, but Graveney said: “There can be no more humbling experience than to visit Jamie at his converted bungalow in Marske and admire his courage and optimism.”

David Graveney speaks during the PCA Long Room Dinner at Lord’s this year

David Graveney speaks during the PCA Long Room Dinner at Lord’s this year

The PCA have become an enveloping organisation, dealing with everything from mental health to motor insurance. “I feel very fortunate to be playing in this era,” said Daryl Mitchell of Worcestershire, the current chairman. “I think what Fred and the boys did 50 years ago has stood us in good stead.”

And yet. It didn’t seem to me as though envy of the young was the overwhelming mood of the gathering. For a start, as is traditional in all hospitality tents and boxes, the sport laid on for them was not a primary concern. It was hardly a dull game. Twenty-five wickets had fallen on the first day, and it was over around teatime, to the consternation of Gloucestershire officials – as two days’ festival takings crumbled to nothingness – and the complete indifference of the old pros.

“Have you watched a single ball?” I asked Chris Old. “No,” replied Chilly firmly. “I’ve seen two balls. Two wickets.” He captured the old pro’s pride in knowing precisely when to watch. Old was just one of a crowd of Test players scattered round the tent – there was MJK and Giff and Shutt (hair jet-black still) and Steely (hair steel-grey still, though I think if anything he looks a bit younger) and Proccy and Foxy (whose beard is more George V than rabbinical), dear old Chat and Percy and more*… Nearly all were as instantly recognisable – except Foxy – as in their heyday. And that was true not only of the Test players. Because up to the 1980s, county cricketers quickly got established both in the community of the circuit and in the minds of its distant followers.

Chris Old (C) was Man of the Match when England and Pakistan met in the first Test in 1978

Chris Old (C) was Man of the Match when England and Pakistan met in the first Test in 1978

“There was no money, no security, no central contracts. So the camaraderie was much stronger. It wasn’t about money. It was about playing a game of cricket. Now it’s a livelihood.” My notes suggest it was Neal Radford, a quite intense man, who said that. But, you know, it was a long day and I had a lot of conversations, and the notebook ended up more illegible than usual. It might have been blithe Pat Pocock. Or Kevin Emery. They were both part of the same group, still lingering after tea. It could have been anyone, really. Because they all seemed to feel the same: yes, they were treated badly; but by crikey they were great times. As Don Shepherd put it: “When you went for a win and there was a two quid bonus on it, you never thought of the money, you just wanted to win the game.”

Back together were men forever linked on the field. D. H. K. Smith and P. J. K. Gibbs, the watchful Derbyshire openers from days of greentops and mordant humour; a trio of umpires – Ken and Roy Palmer and David Constant – in echelon round the same lunch table, more like a slip cordon. And then there was little Brian Crump and Ray Bailey. For them it was another 50th anniversary: in 1967, the summer Rumsey was finalising his plans, the pair bowled unchanged for Northamptonshire against Glamorgan at Sophia Gardens, taking all 20 wickets. Neither looked much older.

I wandered with them round the ground for an ice cream – not, we all agreed, quite as good as the Gallone’s sold at Northampton. Then they moved on to 1965, the year they coulda-woulda-shoulda won the Championship, but got done on the line by Worcestershire. “Second in the Championship! I got a ballpoint pen,” recalled Bailey. Crumpy was outraged. “I never got a ballpoint pen!” he wailed.

At lunch the roll was read of newly absent friends, those who had died since the last gathering. Not everyone had heard each item of news. Jaws dropped from time to time; some guests stared for a moment or two into space as they digested a loss; there was the odd sotto voce “bloody hell”. The undercurrent of sadness never quite went away, but nor did the sense of continued renewal.

Chris Old told me how he sat at home one day watching a Yorkshire and England batsman smack it through the covers. “‘I’ve just seen David hit a four,’ I shouted. ‘You mean Jonny,’ came an exasperated female voice from the other room. ‘No, I don’t. It was exactly like his dad.’”

But as tea was served and the on-field players vanished towards their fancy cars, the late-stayers turned to what has been lost from the game. It was all about comradeship, and the effect on the cricket itself. County pros now might go years without playing against some teams, except perhaps in a Twenty20. They hardly ever come up against any England stars. And, between the warm-downs and the ice baths and the rest of it, they might never even have a friendly conversation with their opponents, let alone a pint.

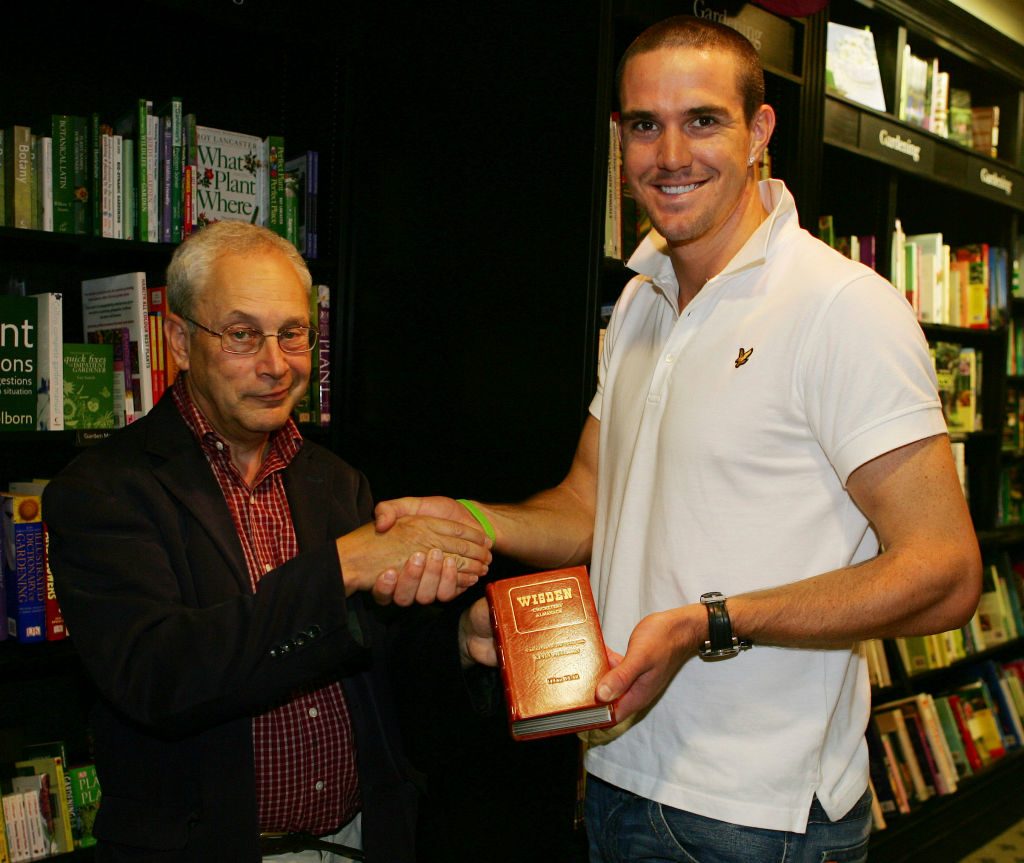

Kevin Pietersen is handed a Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack by then editor Matthew Engel in 2006

Kevin Pietersen is handed a Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack by then editor Matthew Engel in 2006

“Spin bowling has gone down and down and down,” said Pocock. “There’s a lack of experience and knowledge being passed on.” The Surrey seamer Graham Monkhouse said: “I’m still involved with club cricket and it’s just the same in that. One team’s over here and the other’s over there. And they never chat.”

Monkhouse added that the best advice he ever had came in the bar from Jack Birkenshaw, when he was umpiring. “He said, ‘Son, if you ever want LBs, get closer to the stumps.’ ” That sort of conversation happens less too. The last of the autograph seekers were still there as I left. At the start, a fair-sized group of kids had been on the far side of the ground. They were long gone now, not much interested in the players, past or present.

They had been in the nets doing cricket-related exercises, which offered far more inclusive fun than just watching, or sticking them on the field with a hard ball, and few having anything to do. But they were learning cricket as a foreign language; maybe they will fall in love with its grammar and vocabulary, as my generation – gifted or not – did with our peers through our games in the back gardens and back alleys of England, and as kids still do in Karachi, Kolkata and Kandy.

But probably not. So I wondered about them. And I wondered too about Daryl Mitchell. Will he be back at Cheltenham for the centenary gathering, an elder statesman of the game, reminiscing with his contemporaries about the good times, the fun he had, what’s wrong with cricket in 2067, and how this lot don’t know they’re born? I do hope so, because that’s the way it should be.

Don Shepherd bowls for Glamorgan during a John Player League match versus Hampshire, August 1970

Don Shepherd bowls for Glamorgan during a John Player League match versus Hampshire, August 1970

Six weeks later, a week after his 90th, the news broke that Don Shepherd had died. In 2018, his name will be read out, and there will be sadness at his absence. But he lived the contented life of a fulfilled county cricketer. And, as he said to me in that tent last summer, he was a very lucky boy.