Born in February 1931, the incomparable Fred Trueman was perhaps England’s greatest fast bowler: he was certainly the most charismatic. On his retirement, another Yorkshire and England paceman Bill Bowes paid this tribute in the 1970 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack.

Read more features from the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack

Previous Almanack feature: On top of the world: England’s great Ashes summer of 1953 – Almanack

Greatness is a relative term, but anyone making a study of the career figures of Fred Trueman could be forgiven if they claimed he was the greatest fast bowler of all time. He has more victims in Test cricket than any other bowler. In a career which began in 1949 and ended with his retirement at the end of the 1968 season he took over 2,300 wickets at 18.3 each and apart from obtaining all ten wickets in an innings he claimed almost every honour in the game.

Trueman took 307 wickets in 67 Tests for England

Trueman took 307 wickets in 67 Tests for England

He performed the hat-trick on four occasions, claimed five wickets or more in an innings 126 times, and was credited with ten wickets or more in the match 25 times.

As a hard-hitting batsman he hit three centuries. From the boundary edge he could throw low and accurately into the gloves of the wicketkeeper with either hand. He was a very good fieldsman at short-leg and mainly in that position he took 438 catches.

An avid student of the record books and with a tremendous memory for facts and figures, Trueman could no doubt fill in most of the details of his performances and compare them with his contemporaries, but he would not lay claim to greatness. He would be happy to be classed with the other fast bowlers of his time and in particular with Lancashire’s Brian Statham, for whom he has a great admiration and with whom he opened the bowling for England so many times.

Most batsmen, especially those who played against Trueman during the years between 1959 and 1964, when I believe he had harnessed his great ability to a shrewd, calculating, assessment of the opposing players, say tersely, “He was a great bowler”. He showed up mediocrity in an opponent in a manner no other bowler of his time could equal.

He had a flair, as any cricketer of top rank must have, for being able to perform above expectations, above himself as it is generally put. In a couple of overs Trueman could transform the whole outlook of a game. Sometimes it was a fluky shot through the slips, sometimes a stroke of copybook perfection that produced the spark that fired him. Sometimes it was for no other reason than that it was time somebody got somewhere.

A pitch, at one moment docile and easy paced, would suddenly become possessed of every kind of devil. Deliveries which had been reaching the wicketkeeper at ankle height would begin to crash into the gloves at chest height. Batsmen would play and miss in a manner which suggested movement from the seam, and if Trueman had the good fortune to get a wicket no one could ride the crest of the wave better. He had the great asset, which the Australian fast bowler Ted Macdonald called giving the new batsman hell. It was rare for him not to leave a mark on any game with a vital wicket, a wonder catch, or a useful score of 20 or 30 runs.

The crowds loved Trueman. Not only had he an ability which they could enjoy; the newspaper men, television commentators and publicity men projected an image they liked.

Freddie was a tremendous talker. In this department he was the greatest. He was never silent – except during his actual run up to bowl and in the delivery action; it would have been a pity if anything had marred this beautiful, sometimes awe-inspiring, sight. He ran the length of another cricket pitch to bowl. Some critics said he ran much too far, but Trueman himself said he felt better that way.

This was the perfect answer and it meant much more than the opinion of Ranjitsinhji who thought all fast bowlers should take a long run because the longer periods of concentration required from the batsmen had a telling effect. There was a tendency for the concentration to wander.

With a sweet gathering of momentum Freddie, black hair waving, came hurtling to the bowling crease. With no change of rhythm there came the change from forward to sideways motion, the powerful gathering of muscles for the delivery itself, and then the explosive release. A perfect cartwheel action, with every spoke of arms and legs pointing where the ball was to go – the batsman seeing nothing but left shoulder prior to the moment of delivery – gave the ball its 90 mph propulsion. There was the full-bodied follow-through to the action, a run through while he braked, which worried umpires if he got too near the line of the stumps and then, a hundred to one, more talk.

Sometimes it was to tell the batsman how lucky he had been. Sometimes it was to indicate to all and sundry how unlucky he, Trueman, had been; to congratulate a fieldsman on a good stop; to tell the skipper where he wanted the fieldsman to go; or to mutter darkly to himself under his breath. But he talked.

Silence is golden – Brian Close (second from left) would often send Trueman (right) to fine-leg, much to the dismay of the bowler

Silence is golden – Brian Close (second from left) would often send Trueman (right) to fine-leg, much to the dismay of the bowler

He talked in the field to anybody who would listen. He talked in the dressing-room to such an extent that his Yorkshire team-mates seldom answered back because this was encouragement, and as a result half an hour before the start of play in any match Trueman could invariably be found still talking in the dressing-room of the opposing team where the audience was more polite.

He had a rich fund of stories, some of which could have been told in Sunday school. He had a knack of giving weight even to a triviality and no reporter ever went to him in vain for a story. There was a blunt directness about him and the interviewers successfully got this image over to the public. At times he revealed a sword-like wit but the punch line was often just as cutting. Fred’s unhappiest moments on the cricket field were when his skipper, Brian Close, sent him down to the fine-leg boundary, twenty yards in from the spectators, where he could find no one to talk to.

One can only guess the innermost thoughts of opposing batsmen when Trueman, after holding court in their dressing-room, got to his feet about fifteen minutes before the start of play. “So you’re batting, eh? George” (looking at the No.1 batsman), “I shall get you wi’t new ball. Charlie, I’ve no need to worry about you.” Then looking round the whole room he would add, “I’ve got a few candidates today” and his parting shot would be, “I only want a bit of luck with you, skipper, and I’ve got another six or seven wickets.”

This was the Trueman known by the other players and most of them could add a little personal reminiscence. Ken Palmer, who began his career with Somerset in 1955, describes going in to bat against Yorkshire to join his captain, Harold Stephenson. “Stevie hit Trueman for four, not a very good shot, and Trueman glared his disapproval. When he was walking back to his bowling mark, Stevie called up the pitch to me, ‘Ken, just tell Trueman to move that bit of paper that’s blowing about at the back of him.’

“I was a bit hesitant about doing it, but I’d been instructed and I was a new boy. I went up to him. I didn’t know whether to call him Mr Trueman, Freddie, or what, and finally I said simply, ‘Skipper wants you to move that bit of paper before you bowl the next one.’

A fearsome quick with plenty of wit

A fearsome quick with plenty of wit

“Freddie looked at me, then the skipper, and then at the bit of paper and said, ‘Well, just go and ask your skipper who the ‘ell he thinks I am. Tell him I’m not the corporation dustman.’”

In 1961 the Derbyshire wicketkeeper, Bob Taylor, played his first match against Yorkshire and pushing forward to Trueman scored a couple of runs straight back up the pitch. Trueman, trying to recover from his follow-through and field the ball, slipped and fell. He stayed on the ground until the batsmen had finished running and then glared at Taylor and asked, ‘Can you hook ‘em an’ all?’ “I expected the next ball to be a bouncer,” said Bob, “but instead he bowled me with one of the best yorkers I’ve ever had.”

And the story which many England players who were on the ship to Australia in 1961, love to tell is when Gordon Pirie was pressed into action to take the boys in PT and general fitness training. Said Gordon to Trueman one day, “Freddie, it’s your leg muscles that want strengthening…” Before he could go any further Freddie exploded, “What? Well, let me tell you they’ve held me for 1,000 overs and more this year already.” He looked pointedly at Gordon and with the cutting edge in full evidence continued, “And they’ve never let me down when I’ve been performing for England.” It’s more than a lot of sportsmen can say.

A fluid action built on the strongest pair of legs

A fluid action built on the strongest pair of legs

The conversation was at an end. There’s no arguing with this kind of logic. Nevertheless, I think Freddie had my sympathy. If ever a fast bowler had a strong pair of legs that man was Trueman. Indeed, apart from a little stitch in his early years as a fast bowler Freddie kept amazingly clear of injuries. He made me green with envy when, after bowling eight overs flat out, he could field at short-leg crouching down on his haunches, sometimes sitting miner fashion on his heels, for a rest! Most fast bowlers doing that after eight overs would want a winch and not a helping hand to get them up again.

These three stories almost tell the career of Frederick Sewards Trueman, 5ft 10½in, who was born at Stainton (near Doncaster) on February 6, 1931 and was one of a family of eight to a miner. His father, Allan Thomas, was a well-known local club cricketer, left-arm bowler and batsman, and fostered a liking for cricket throughout the family.

As a young fast bowler with his school team, Trueman was hit in the groin by the ball and for a couple of years was an invalid and in danger of losing his leg. Fortunately the doctors won. Freddie returned to his school team as a fast bowler, earned selection for the Federation team, joined the junior section at Sheffield United’s ground in Bramall Lane, and from there was invited to attend the Yorkshire nets for special coaching. The coaches liked what they saw. Just after he was eighteen, without playing for the second team in any sort of game, F. S. Trueman was chosen to play for Yorkshire against Cambridge University.

They knew that with such a glorious action to work on Trueman must come good and although he had not the full strength of manhood and was without the necessary control to be an immediate star he was ripe for grooming.

Yorkshire played Trueman in nine games, including one with the New Zealanders at Sheffield at the end of July, and altogether he took 31 wickets at a cost of 23 runs each. He was carefully nursed by his captain, Norman Yardley, who like every other player in the side could see the promise in this self-confident, almost arrogant young man who wore a yellow tie with a red dragon and thought he was the bee’s whiskers playing for Yorkshire.

To Norman Yardley fell the job of encouraging, letting him get an easy wicket here and there against the tailenders and fanning an enthusiasm and willingness to bowl that more often than not needed dampening.

It was with a chuckle rather than an intentional compliment that Yardley would say, “I think it’s time for Fiery Fred to have a bowl now.” But Fred was not as good as he thought himself to be. Yorkshire turned to a schoolteacher, Bill Foord, to fill the bowling position because they thought the latter was a better prospect and, during the August holidays, was readily available.

Trueman, who strained a back muscle in the game against the New Zealanders, was not called upon again that season and the next he heard from Yorkshire was when he received his invitation to attend the nets during the winter once again for special coaching.

Unintentionally, Yorkshire had given Trueman’s pride a tremendous blow. Yorkshire did not give a damn about him. From now on he would not give a damn about them. He kept up this attitude to authority almost throughout his career, but with that greater characteristic that stamped all his cricket there came the determination “To bloody well show them.”

Yorkshire did not think he was good? He started talking in order to convince himself he was good and few people who knew Fiery Fred in later life realised his continual chatter stemmed from an inferiority complex.

To try and convince opposing batsmen he was good he overdid his use of the bouncer which meant presenting runs on placid surfaces – and was the real purpose behind Somerset’s skipper Stephenson, asking for the bit of paper to be removed.

Trueman’s (back row, far right) first Ashes Test was the famous Oval encounter of 1953

Trueman’s (back row, far right) first Ashes Test was the famous Oval encounter of 1953

Throughout his career Trueman tended to overdo his use of the bouncer but, as he got stronger, it was something to be feared and watched for, even on the most placid surface. The visiting India side in 1952 first felt the impact of Trueman grown into the strength of manhood. He took 24 wickets in three Tests and in the match at Leeds, in front of his own spectators, I recall the excitement when India lost their first four wickets without a run scored, and Trueman taking eight wickets for 31 runs, put India out in eighty minutes for 58 runs. Riding on the crest Trueman seldom bowled faster and he admitted, “I’d nothing else to do but bowl straight.”

The Cricket Writers’ Club elected him the best young cricketer of the year. The success gave Freddie’s talk more authority and as he found in later years there was a great deal of success from bowling straight – and very fast.

At this time the former miner and now England cricketer, Freddie Trueman, was serving his first year of National Service in the RAF. He could seldom be given leave to play for Yorkshire but in the national interest he could play for England. He claimed only 61 wickets in first-class cricket that season and in 1953, when the England selectors wanted him for only one Test against the Australians, he had only 44 victims.

It could be said that Trueman began his career as a cricketer during that winter of 1953/54 when, with his National Service completed, he was chosen to tour West Indies. And it was at this time his troubles began.

The pressmen found plenty of sensational copy in his willingness to talk. His antagonism got him into trouble with umpires and at times the crowd, too. He had to be reminded that the England captain, Len Hutton, was now no longer a Yorkshire colleague but The Boss. If any cricketer did or said anything mean on this controversial tour Freddie got the blame. He was, to many people, a bother-causer.

The England captain and selectors somewhat understandably turned to Typhoon Tyson as their fast bowling partner for Statham. Despite 134 wickets in 1954 Trueman missed the tour to Australia and did not play in another Test match until Tyson blistered his heel and had to withdraw from the Lord’s Test of 1955 against South Africa.

In 1956 Trueman was chosen for two Tests against Australia but this season was for him the worst experience of unfitness, sciatic nerve trouble, blisters and then a strained side – plus a very wet summer. His final return was only 59 wickets and he was omitted from the England team to tour South Africa.

Newsmen, hoping for another sensational Trueman story, were assured by the chairman of selectors and the MCC secretary that there had been no victimisation and Freddie himself found consolation in these assurances. Once again came that determination to show ‘em – and of course, there was now considerable experience behind his efforts.

This was the start of the period mentioned earlier when Trueman, by general opinion, was a great bowler. And he was helped considerably by the Yorkshire captain, Ronnie Burnet, who took over the side in 1958. By consideration and encouragement, leading and never driving, he drew the best out of Trueman.

Freddie now had the ability to suggest to a batsman that he was going to bowl a bouncer and send down a yorker and as he grew in confidence he began to feel he could answer back. Occasionally he guessed badly. He found the Yorkshire committee supported the captain Vic Wilson when Trueman arrived late for a game at Taunton. Fred later refused to subscribe to a retirement present for Wilson saying, “What, show my appreciation for a chap who sent me home?” Again there was no refuting the logic but Mr Burnet wangled a compromise with Freddie’s wife Enid.

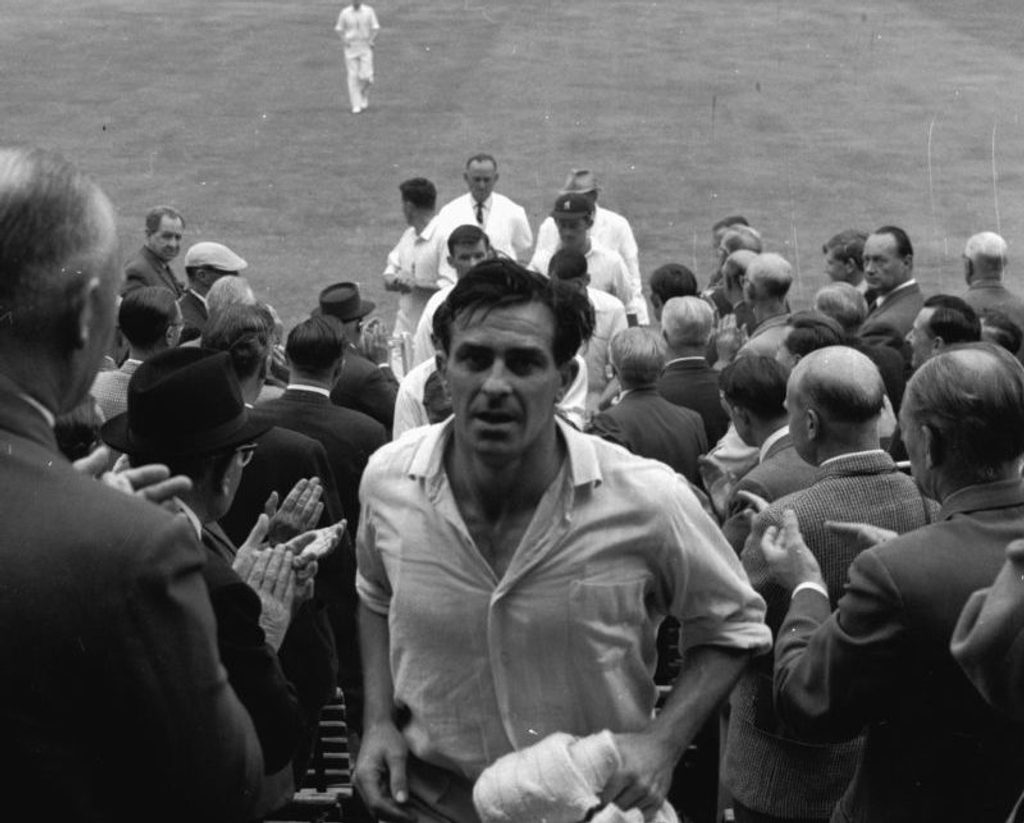

Trueman soaking in the applause of the Oval crowd after collecting his 301st Test wicket

Trueman soaking in the applause of the Oval crowd after collecting his 301st Test wicket

All these things made Trueman a character the game and the public enjoyed, and yet, while giving this impression that he knew it all, there was that extreme and opposite side to him which responded to confidence, and was ready to listen to a helping voice. Then he could charm more than dominate.

Towards the end of his career when seniority earned him the right to lead Yorkshire whenever D. B. Close was absent, he proved himself a capable and knowledgeable captain and had the high distinction of leading Yorkshire to victory over the touring Australian team. The honour put another yard of pace into his bowling. He wanted to prove he was still good.

He enjoyed being told he was good, too, and on these lines I cherish the story of Richard Hutton after Freddie had returned yet another of his many five-wicket performances. “Well bowled, Fred,” he said. “Out-swingers, in-swingers, bouncers, yorkers, you bowled the lot. Tell me, did you ever bowl a plain straight one?” Quick as a flash came the reply, “Aye, one. But it was so fast it went through him like a dose of salts and knocked all three down.”

Fiery Fred held the stage for twenty seasons. In major or minor parts he commanded attention. He received a benefit of £9,331 in 1962 and bow(l)ed out in September 1968.