Trueman, Frederick Sewards, OBE died on July 1, 2006, aged 75.

Read more Almanack tributes

Fred Trueman was not just a magnificent fast bowler, he was one of cricket’s greatest personalities. His Wisden obituary in 2007 remembered a character who was more complex than he appeared.

Fred Trueman was – ignoring his own grander claims – probably the greatest fast bowler England has produced. He was at the heart of the England team for more than a decade, during which time it usually beat the world. He was also English cricket’s most enduring and best-loved character, representing a certain kind of Yorkshireness – chippy, forceful, sometimes humorous – that spread his fame far beyond the game and maintained it long after his retirement.

Harold Wilson, the former prime minister, called him the “Greatest Living Yorkshireman”, and only an unusually fulsome Wilson-admirer would have come up with another contender. Jokes, anecdotes and myths clung to him all his adult life: he was the most talked-about figure in the game until Ian Botham arrived in the early 1980s; and until Andrew Flintoff stole the moniker 20 years later, he was instantly recognisable by the simple syllable: “Fred”.

Trueman was born in a terraced house just outside Stainton in the mining country south of Doncaster. He weighed, if not a ton, then a stone when he was born, which must have been an omen. His father Dick was a former stud groom, forced down the pits by the hard times, and weekend cricketer. He was determined his children would do better. Fred’s determination with a ball in his hand was obvious from the start: “We never got a chance to bat properly and it made us cry,” his sister Florence recalled later.

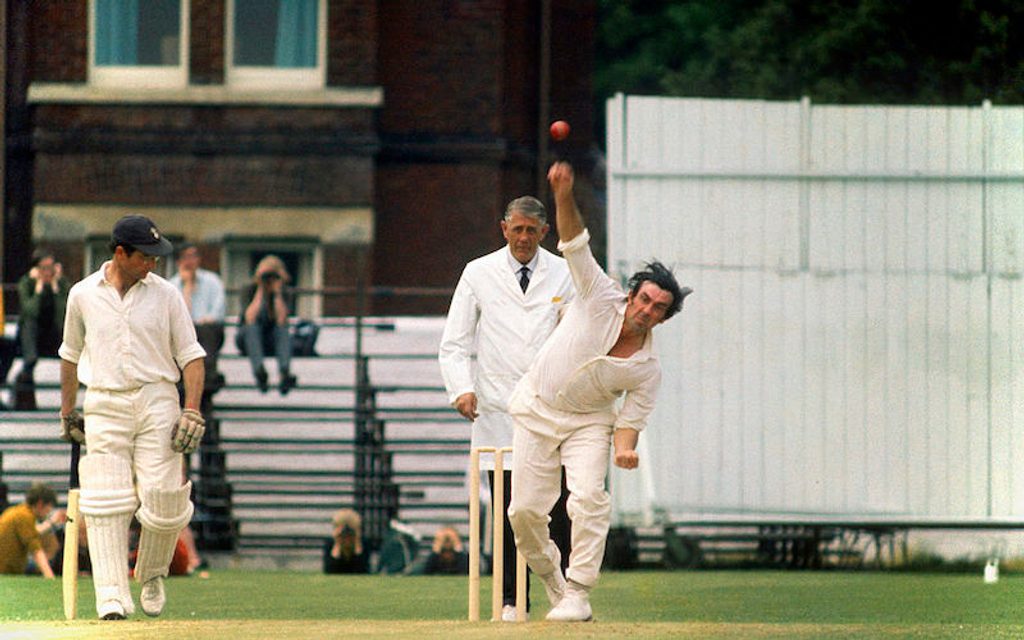

Trueman bowling for Yorkshire, who he spent 18 years with as a player

Trueman bowling for Yorkshire, who he spent 18 years with as a player

Nothing was a certainty, though. Aged 12, at secondary school in Malton, he was hit – batting without a box – in the groin; he was off school for a year, out of the game for two, and there were fears that he might lose a leg. But back he came. At 16, he was bowling fast for a local club, Roche Abbey. He was noticed by Sheffield United, who played at Bramall Lane, and from there was picked for a Yorkshire Federation tour, in effect the county third team. Though the £6 cost was a lot for the Trueman family, his father happily paid.

Meantime, young Trueman had to work: as a bricklayer, until he told the foreman to “bugger off “, and at the pit – though never down it. But by 1949 he had achieved his first ambition: “Yorkshire gave a trial to three young players,” Wisden reported in one of its least fine hours, “Lowson, an opening batsman, Close, an all-rounder and Trueman, a spin bowler.” He forgave that insult, but characteristically never forgot it. Just as typically, while Close moved rapidly into the Test team, and Lowson followed, Trueman had to battle for everything.

Though quick, he was wayward and sometimes expensive, and in the dour, unforgiving atmosphere of the Yorkshire dressing-room and committee room in that era, the negatives assumed great importance. He was also loud-mouthed and seemingly insensitive. Indeed, England’s selectors seemed more interested than Yorkshire’s. In 1950, he was picked for The Rest in the Bradford Test Trial, the match immortalised by Jim Laker’s 8-2, but Yorkshire dropped him in favour of John Whitehead. He was downhearted enough to think about joining Lancashire. But some people recognised that they had a potential treasure; it was his captain, Norman Yardley, that first christened him “Fiery Fred”.

Alec Coxon’s sudden departure after that season meant that Trueman’s time had surely come. In 1951, he almost bowled Yorkshire to victory over the South Africans and did bowl them to a stunning win over Nottinghamshire, taking 8-68. Not merely was he not picked for the next match – the team had already been chosen – he ended up as twelfth man for the Second XI at Grimsby. But in the return match at Trent Bridge, he was even more devastating, taking 8-53. “It was the start of the Trueman era,” wrote Don Mosey, in his biography Fred Then and Now.

He still had to do his National Service. But he joined the RAF, and got a nearby posting and a sympathetic station commander, so he could play plenty of cricket. At that stage, the RAF was probably less hierarchical than Yorkshire County Cricket Club, and he coped with the vagaries of service life rather better than he did with the Yorkshire committee. And he was hauled from there – as AC2 F. S. Trueman 2549485, a sports storeman – to play for England in 1952. There have been extraordinary debuts before, but never one that quite matched this, as India were reduced to 0-4. Six weeks later he took 8-31 as India were bowled out for 58, most of them fearfully backing away to square-leg. He took 29 wickets in the four-Test series at 13.

But still his progress was not smooth. He was sharp-tongued and insubordinate, and more vulnerable than anyone seemed to realise. Around this time, the first stories spread that eventually developed into the great canon of Trueman legend, including the (uncorroborated and implausible) allegation that he had told the Indian High Commissioner: “Pass the salt, Gunga Din.” In 1953, England again ignored him, until the final Test, when England regained the Ashes, and Trueman took four important wickets. “Erratic, yes; wild, most certainly; but full of fire and dynamite,” wrote Jack Fingleton. But these virtues were questionable on his first tour, a politically charged trip to the Caribbean that winter, and not all that effective in a cricketing sense either.

“Mr Bumper Man” Trueman had a turbulent international career

“Mr Bumper Man” Trueman had a turbulent international career

Though he did well in the MCC match against Jamaica, “Mr Bumper Man” became a figure of fun on the Kingston stage: “What shall we do with Freddie Trueman? What shall we do with Freddie Trueman? Trueman’s bowling bumpers. Not that it mattered. Four hundred odd the scoreboard rises Four hundred odd the scoreboard rises He’s still bowling bumpers.”

He was dropped from the Test team after the opening game and missed the next two: his run-up became stuttering on the matting pitches. However, the words did not become stuttering in the face of erratic local umpiring. “As a friend – and I admire many things in this blunt Yorkshire lad,” wrote Alex Bannister in Cricket Cauldron, “I urge him, with all my force, to make a serious and determined effort to keep himself in control.”

He was picked one tour too early, Bannister thought later. The upshot was that, though he was devastating in England in 1954, with 134 wickets at 15, Trueman was not picked for the Tests against Pakistan and, devastatingly, passed over in favour of Frank Tyson for the Ashes tour. It remained a source of grievance all his life, the more so since Tyson returned home a hero.

For the next two years, he remained a fringe Test player, and treated like a naughty child, which came to a head before the Headingley Test in 1956 when Gubby Allen put a handkerchief down in the nets and instructed the great bowler, in front of a gathering Yorkshire crowd, to hit it. “Fred felt diminished and humiliated,” wrote Mosey. He was excluded from the South African tour that winter too.

Trueman during the sea voyage home to England after the 1954 tour of West Indies

Trueman during the sea voyage home to England after the 1954 tour of West Indies

By the spring of 1957, Trueman had played just seven Tests after his opening series against India. But now finally he became accepted. Until this point, he had partnered Brian Statham in the Test team only four times. Now it became the norm, and would remain so for the next six years. Trouble was never that far away with Fred: there was an exchange of bouncers with the even fierier Jamaican Roy Gilchrist in 1957, with Fred threatening to “pin ‘im to t’ bloody sightscreen”. But he managed to rise above most of the vituperative politics of the Yorkshire dressing-room. And he was by now as complete a fast bowler as the world had ever seen.

“It is a mistake to think of Fred Trueman as simply a bowler of speed,” wrote John Arlott in Fred: Portrait of a Fast Bowler. “He had out-swing, in-swing, a yorker that only Lindwall could match… Indeed, he shared with Lindwall the rare ability to ‘do’ as much as a fast-medium bowler at a fast bowler’s speed.” And he had an extraordinary capacity for hard work that would make a modern bowler gasp. He came back – his own reputation undamaged – from England’s unhappy Ashes tour of 1958/59 to play all five Tests against another weak Indian team in the hot summer of 1959, taking 24 wickets at 16. But in all, he bowled nearly 1,100 overs, and took 140 wickets.

He had a much happier tour to the West Indies the following winter. For once, and rather improbably, he got on with the tour manager, R. W. V. Robins. He made great use of his swinging yorker, and showed the crowds his humour, not his temper. When Statham flew home, Trueman was made senior professional. He played ten Tests in the first eight months in 1960 and took 46 wickets – and the small matter of 132 in the County Championship as well.

At Headingley in 1961, he had perhaps his finest hour of all, or finest 25 minutes. On a pitch offering no help to pace, he shortened his run, relied on cut, and dismissed Harvey, O’Neill, Simpson, Benaud and Mackay in the second innings without conceding a run. The crowd’s response was rapturous, and England beat Australia for the first time since Laker’s Test.

Fred Trueman is widely regarded as one of England’s greatest ever seam bowlers

Fred Trueman is widely regarded as one of England’s greatest ever seam bowlers

But controversy was never far away even now. In 1962, he captained the Players in what turned out to be the very last match at Lord’s against the Gentlemen. He went down to Taunton – “knackered” – for Yorkshire’s match there, overslept, and was sent home by the captain, Vic Wilson. The normal furore ensued. The next Ashes tour began with him contemptuously rejecting the fitness regime initiated by the athlete Gordon Pirie on board the Canberra. And, though he confirmed that he was, at 32, still England’s leading bowler – not least with five crucial wickets in the win at Melbourne – he had a third of his £150 tour bonus deducted.

He channelled his grievances into a spectacular performance against the brilliant 1963 West Indians when he (temporarily) got England back into the series with a devastating second-innings burst at Edgbaston. “With his hair escaping in dark and wild curls,” wrote John Woodcock in The Times, “and his run a thing of gathering strength, he took control of the game. Every ball was charged with danger.” Woodcock concluded that on moist English wickets Trueman remained as great as he ever was. “He bowled with his brain as much as with his muscle. Beneath a clouded sky he moved the ball with late and vicious swing; off the seam it cut, like a rattlesnake, this way and that.”

At The Oval in 1964, he became the first bowler ever to take 300 Test wickets, and was cheered there to an extent last seen at Bradman’s farewell. Woodcock pointed out that this landmark did not of itself prove Trueman was the greatest of all time. “Yet on his day he has displayed, to the highest degree, the beauty and skill and the manliness and the terror of his calling.”

He faded out of Tests halfway through the following summer. Until 1968, he continued as a Yorkshire elder statesman in a side which won the Championship three times running (and had to wait until the next millennium to do it again). He also led the county to victory over the 1968 Australians at Bramall Lane. It might have been the moment to retire – Statham went out with a flourish in a Roses match – but the great showman went quietly, with a polite letter to the committee after the season, probably before the committee wrote one to him, once and for all.

But there was no quiet retirement. More deliberately and self–consciously than anyone before (except, perhaps, in his discreet way, Bradman), Trueman turned his cricketing celebrity into gold. He had a rather embarrassing spell doing cabaret in the northern clubs. But eventually this mutated into a cricket dinner speech, for which clubs would invariably pay handsomely, though its mixture of coarse jokes and cricketing egocentricity could be fairly unedifying. He introduced, pint in hand, the TV programme Indoor League. He had a regular column in The People, which was fine, except on the occasions when he was expected to write it himself.

And he kept playing for another 20 years: briefly in the Sunday League for Derbyshire in 1972 and then – as a daytime counterpart in the nostalgia market to his speaking – for the Old England XI and the British Airways Eccentrics. And for 25 years, with Trevor Bailey, he was the summariser on Test Match Special. Unfortunately, as English cricketing indignities worsened, Trueman found it ever harder to find a kind word for his successors, summed up in his (often misquoted) mantra: “I don’t know what’s going off out there.”

Trueman with his wife Enid and daughter Karen at the birth of their twin son and daughter Rodney and Rebecca

Trueman with his wife Enid and daughter Karen at the birth of their twin son and daughter Rodney and Rebecca

His family life – turbulent during his first marriage to the strong-minded daughter of a mayor of Scarborough – became much happier when he settled down with Veronica. He loved his kids and, increasingly, wintering in Spain, while maintaining a punishing schedule of appearances in Britain. Much of his work was for good causes; and he did much to stabilise Statham’s finances in his old mate’s more troubled old age. Trueman raced around until he was diagnosed with cancer, a few weeks before he died.

The anecdotes kept growing to the point where every cricket story ever told somehow attached itself to Fred. Some, at least, had the ring of truth. One, recalled by Mosey, fits with the scorecard of a game against Tyson at Northampton in 1954. Johnny Wardle was bowled, horribly, by Tyson for nought. “A bloody fine shot that were,” snorted Trueman, as he went out, just before meeting a similar fate. “And a bloody fine shot that were, an’ all,” was Wardle’s greeting to Fred. But Trueman had a knack of getting in the last word: “Aye, I slipped on that pile o’ shit you left in the crease.”

Trueman (right) working for BBC Test Match special with commentator John Arlott (left) at Trent Bridge

Trueman (right) working for BBC Test Match special with commentator John Arlott (left) at Trent Bridge

Yet the image was substantially false. He drank sparingly: what Fred loved was chat, especially about cricket, and most especially about himself. He was also curiously insecure, and soft-centred. He was deeply hurt both by being voted off the Yorkshire committee in 1984 in the midst of the civil war over Geoff Boycott, and by his sacking from the TMS team in 1999. Once again, there was no goodbye, and this time it was not his choice. His speeches became less ribald, more elegiac.

In 2004, at the 364 Club lunch at Headingley, to honour Len Hutton, he made a much-admired tribute, then broke down before the end, overcome by the memories. Fred Trueman died on the morning of a one-day international against Sri Lanka at Headingley. (England were terrible, so it was just as well he wasn’t on the radio.) When the news was announced, there was prolonged, appreciative, applause for him before the minute’s silence.