David Hookes was a brash young star of Australian cricket whose batting lit up the Centenary Test. His tragically early death stunned the nation.

Hookes, David William, died on January 19, 2004, aged 48.

David Hookes died after becoming involved in an argument with a bouncer outside a Melbourne pub, where, as coach of the Victorian state team, he had been celebrating a victory with his players. Hookes was allegedly hit in the face and smashed his head on the road.

News of his death stunned Australia and the cricketing world, partly because of its brutal suddenness and partly because of his larger-than-life personality. He had an impact on the game as cricketer, coach and character that transcended his patchy career record, and more than 10,000 mourners attended his funeral at Adelaide Oval which was televised across Australia.

Fans at the Sydney Cricket Ground pay tribute David Hookes during a One Day International between India and Australia in January 2004

Fans at the Sydney Cricket Ground pay tribute David Hookes during a One Day International between India and Australia in January 2004

After a spectacular career in Adelaide schoolboy cricket and a low-key start with South Australia, Hookes burst to fame in his second season of first-class cricket. In 17 days in February 1977, he scored five centuries in six innings at the Adelaide Oval, all at blistering speed. The first, 163 against Victoria, contained four sixes in an over. A week later he smashed 185 in 191 minutes and 105 in 101 minutes against Queensland. The next week produced 135 and 156 against New South Wales.

Less than a month later, he joined the greats in perhaps the most famous cricket match ever played: the Melbourne Centenary Test. Aged just 21, he strode to the crease looking full of confidence. Then he hit the England captain Tony Greig for five successive fours; he matched him in the lip department as well. Greig had taunted him at the pre-match cocktail party: “Not another Australian left-hander who can’t bat”; Hookes said that at least he was an Australian, not “an effing import”. After he was out for 56, Greig brought a beer to the dressing-room, and said: “Mind if I sip with you, son?”

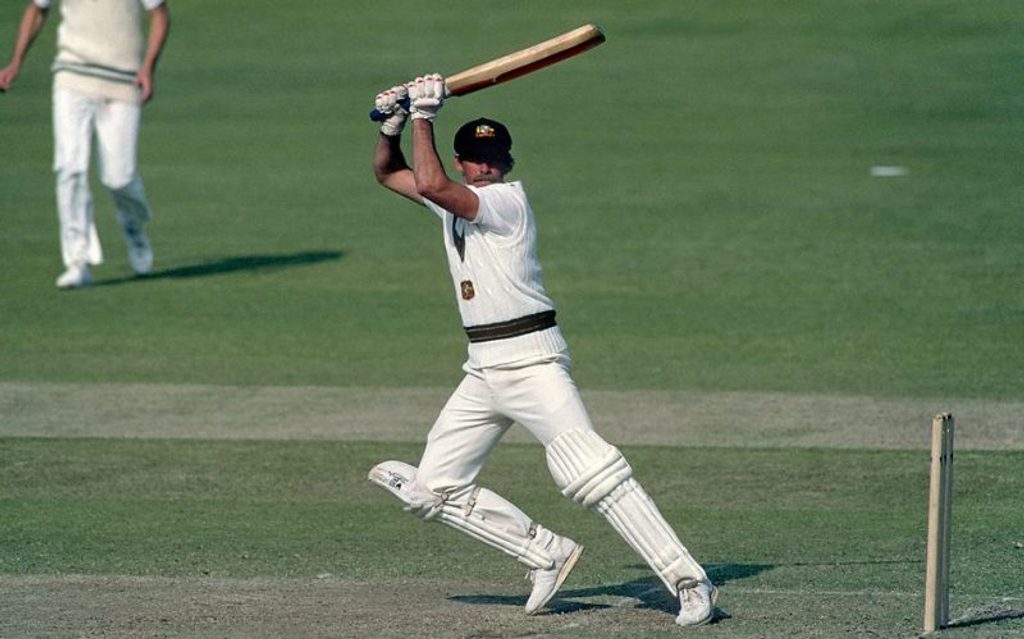

David Hookes in action during the 1983 World Cup in England

David Hookes in action during the 1983 World Cup in England

Hookesy had the cricketing world at his mercy, but a greater game was afoot, and less than two months later it became known that Hookes had joined Greig and most of the Australian team in the rebel venture sponsored by Kerry Packer that became known as World Series Cricket. Logically, his career would have flourished more had he stuck with the official game. But the leading rebel Ian Chappell was his hero, and safety first was never the Hookes style, in cricket or in life.

On the strange, shadowed tour of England that followed, he faded into the general mediocrity of a distracted Australian side, though he made a sweet 85 in the rain-ruined finale at The Oval. When the Packer circus started, he seemed to be running into form and had reached 81 at the Sydney Showground when he was felled by a bouncer from Andy Roberts which broke his jaw. Some felt his batting never recovered its carefree innocence; despite his name, he gave up hooking. Certainly he never recaptured his automatic place in the Australian team. After peace broke out in 1979, he played only two Tests in three years, cast into the wilderness after a pair at Karachi.

Hookes in conversation with Shane Warne (left) Darren Berry (middle) during his coaching stint with the Victorian Bushrangers in 2002

Hookes in conversation with Shane Warne (left) Darren Berry (middle) during his coaching stint with the Victorian Bushrangers in 2002

But in 1981-82 South Australia made him captain, and he led them with panache to their first Shield title in six years. The next year his old batting form came back, and with it his Test place, though his steady performances in the Ashes series were overshadowed by one blazingly angry innings against Victoria. Incensed by a belated declaration by Graham Yallop, Hookes promoted himself and struck a century in 43 minutes off 34 deliveries – the fastest-ever uncontrived hundred in terms of balls received. He made South Australia’s target, 272 off 30 overs, look momentarily plausible; he also made his point, and made it again in the return fixture when he scored an even-time 193. His star was rising again; he was appointed vice-captain to Greg Chappell for Australia’s inaugural tour of Sri Lanka, and smacked an unbeaten 143 in the one Test, at Kandy, the last 100 coming in a session. It was his first, and only, Test century.

But Hookesy had to be Hookesy. He criticised Chappell’s successor, Kim Hughes, on air at a time when he was not scoring enough runs to ride the storm. From then on, his Test appearances were intermittent and indifferent, though he played on until 1991-92, breaking the Shield run-scoring record with the occasional amazing innings, like his unbeaten 306 off 330 balls against Tasmania in 1986-87. His batting was always distinctive: “Gowerish but more brutal” according to Alan Shiell, who helped write his autobiography: “He could be elegant and he was just as vulnerable outside off stump, but he played shots Gower wouldn’t have bothered with, flogging bowlers over wide mid-wicket or hoicking them over square leg.” The egg-shaped Adelaide Oval, with its inviting square boundaries, was made for the Hookes style, and it gave him an edge throughout his career.

Since he was articulate as well as forthright, he became a radio star in Adelaide, and in 1995 moved to the bigger market of Melbourne. Seven years later, Victoria appointed him their coach; when he died, the team he moulded was on the way to their first title in 13 years. They were celebrating a win over South Australia at a pub in St Kilda. Outside, a bouncer, Zdravko Micevic, 21, allegedly threw a punch at Hookes – he was charged with manslaughter.

At Hookes’s funeral, his bat was placed against the stumps, with his cap and gloves alongside; it was a trademark gesture of his when he was batting at an interval, a sign that he would be back. In these circumstances, it was almost unbearably poignant.