The events that made Basil D’Oliveira one of the most significant cricketers in history lay in the future when he was named a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1967.

Basil D’Oliveira went on to make 44 Test appearances, scoring 2,484 runs and taking 47 wickets. When England’s tour to South Africa was called off because of his selection in 1968, he unwittingly began a chain of events that led to more than two decades of sporting isolation for his homeland.

Read Basil D’Oliveira’s Wisden obituary here

The story of Basil D’Oliveira is a fairytale come true; the story of a nonentity in the country of his birth who, because of the colour of his skin, was confined to cricket on crude mud-heaps until he was 25, yet after only one season in the County Championship played for England. No Test player has had to overcome such tremendous disadvantages along the road to success as the Cape coloured D’Oliveira. Admirable though his achievements were against the West Indies in 1966, undoubtedly his triumph in ever attaining Test status was more commendable.

That he did not fall by the wayside of the stony path he was compelled to tread is a tribute to the courage and skill of this player from the land of apartheid. To say that he never contemplated giving up the game before reaching the hour of glory was hardly the case. The hazards he encountered were very nearly too great, even for the stout-hearted D’Oliveira. Suffice to say that of the 25,000 South African coloured cricketers who would dearly love to make county grade over here, D’Oliveira is the first to have done so.

Hundreds of others are doomed to spend their lives in a class of cricket far beneath their skill. They will stay because no one ever sees them in this unfashionable outpost of the game. Born in Cape Town on October 4, 1934, Basil Lewis D’Oliveira inherited his father’s love for the game, but until he was 15, practically the only cricket he played was in the street. There were no facilities at either of his schools, St Joseph’s Catholic or Zonnebloem Training College, as money for the promotion of school sport was non-existent.

The England side after defeating West Indies at The Oval, August 22, 1966. Basil D’Oliveira is third from left in the back row

The England side after defeating West Indies at The Oval, August 22, 1966. Basil D’Oliveira is third from left in the back row

His school days over, he joined St Augustine’s, the club for which his father, Lewis D’Oliveira, played as an all-rounder for something like 40 years. There, in one of the South African leagues for non-Europeans, young Dolly began to blossom under the guidance of his father, as a right-handed batsman and medium-pace bowler. His team-mates would walk miles to a suitable strip of grassless earth, sand or gravel over which to lay a mat after first preparing their pitch with a spade and wheelbarrow. D’Oliveira thought nothing of walking 10 miles to his home ground. The alternative was a four-mile stroll to the nearest bus stop.

His club shared the ground with other teams and it was not uncommon for square-leg in one match to find himself standing near third-slip in the next. Yet, these primitive conditions served only to imbue D’Oliveira with a zest and enthusiasm for the game. He was deeply impressed on his visits to first-class matches in Cape Town, in particular, to see Compton, Harvey and May.

He never missed an opportunity to study closely the manner in which these and other great batsmen moved about the crease and into their strokes. He reasoned for himself why any particular stroke was made, and soon, reports of his own phenomenal scoring feats began to trickle through.

D’Oliveira scored 80 centuries in the Cape and once hit 225 in 70 minutes. In a federation tournament, he thrashed 168 in 98 minutes, and in another innings, made 46 in an eight-ball over. English professionals who went to South Africa coaching during the winter, spoke of him as a natural player who moved well and struck the ball hard.

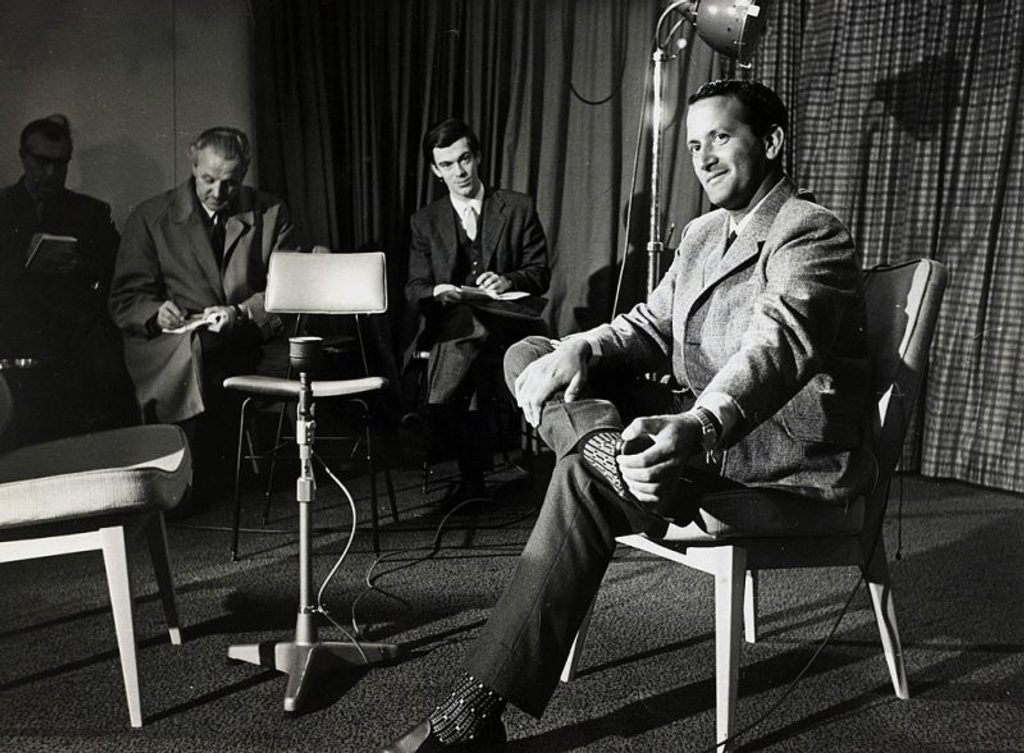

Basil D’Oliveira sits at a press conference, 1967

Basil D’Oliveira sits at a press conference, 1967

Yet, it seemed, it was not easy to convince anyone that he could be a top-class player against top-class opposition. He played, however, in one or two testimonial matches in South Africa against White teams, then against the Kenya Asians, and went on an all-coloured team’s tour of East Africa.

For a couple of years, John Arlott, the broadcaster and cricket writer, tried to get people in England to take an interest in D’Oliveira, and eventually, with the aid of the urgings of two other journalists, Middleton, of the Central Lancashire League, after failing to get several better known players, offered him a contract at £450 for the 1960 season. He was then 25.

Raffles, fêtes and matches were organised in the locality of his tenement home in the coloured quarter of Cape Town to raise his fare to England. As an £8 10s. a week machine-minder for a printing firm, there was little scope for savings of his own, with a wife and baby to support. For an unproven player with the Manchester suburban club, he was little or no better off, to begin with. He had just enough to live frugally during the summer and pay his return fare home to bring back his wife.

At Middleton, D’Oliveira’s competitors included Garry Sobers, Cecil Pepper, John McMohan and Salim Durani. So that with only 25 or so runs and three or four wickets to show for his endeavours after five matches in the League, he was all set to pack his bags. He felt he was clearly out of his depth. Then, almost suddenly as the weather warmed up and pitches became faster, runs began to flow from D’Oliveira’s bat as in his native South Africa. By the end of his first summer, he had made 930 runs, averaging 48.95, which was slightly better than Sobers and the best of the League.

For good measure, he gained 71 wickets at 11.72 each. Middleton’s gamble had paid off. The coloured cricketer from the Cape stayed for four years. When he first arrived in England in April 1960, the extremely modest and well behaved D’Oliveira was quite stunned at being treated as an ordinary human being unaffected by any colour bar. He would have been perfectly content to have spent the rest of his life in Middleton, where he established himself with more than 3,600 runs for an average of over 48, and 238 wickets at under 17 each.

D’Oliveira considers he owed a great deal in his successful switch from matting to grass to the kindly advice and help he received at Middleton from Eric Price, the old Lancashire and Essex left-arm slow bowler, who played in the league as an amateur. Hours and hours of net practice, sometimes with only schoolboys for company, illustrated his tremendous will to succeed.

It was Tom Graveney who persuaded Dolly that he was good enough to be a success at the county level. They were on a private Commonwealth tour together, and in the face of competition from Gloucestershire [after Lancashire had turned him down], D’Oliveira joined Worcestershire. While qualifying by residence, he spent the 1964 season with Kidderminster in the Birmingham League, averaging 78.44, and played the occasional non-Championship match. In the latter, he showed his potential with 370 runs [average 61.66] in eight first-class innings, including 119 at Hastings for A.E.R. Gilligan’s XI against R.B. Simpson’s touring Australians.

And so to 1965, his first year of Championship cricket. If there were any lingering doubts that at the age of 30 his weaknesses would be exposed, these were soon dispelled. He made five centuries, totalling 1,523 runs [average 43.51], and he and Graveney were the only batsmen in the Championship to exceed 1,500 that season. D’Oliveira also took 35 wickets, proved himself in the top flight as a slip fielder, and gained the distinction in his first county season of helping Worcestershire in no small measure to retain the Championship pennant.

As his captain, Don Kenyon, remarked at the end of a memorable summer, “D’Oliveira did everything we hoped he might do and a lot more… all the predictions that a turning ball might find him out proved utterly false.” D’Oliveira himself considered that it was in 1965 he played his finest innings — 51 not out on a turning pitch at Cheltenham against Allen and Mortimore.

Undoubtedly the most memorable year of his life was 1966, by which time he had become a British citizen. Although he had shown every promise in MCC matches at Lord’s, to be selected for England against the West Indies was beyond his wildest dreams. It was D’Oliveira himself who said after his Test debut at Lord’s “This is a fairytale come true. Six years ago, I was playing on mudheaps. Now I have played for England and met the Queen; what more could I possibly ask?”

Basil D’Oliveira went on to play 44 Tests for England

Basil D’Oliveira went on to play 44 Tests for England

It set the seal on the happiness he and his charming wife, Naomi, and sons Damian, aged six, and Shaun, aged two, have found since coming to this country. He went on to play successfully in the three subsequent Tests, making the jump to international grade in the same facile manner of his previous steps up in status. England had gained not only a skilful cricketer but a man of rare fighting qualities.

People who have delighted in the manner in which he has savaged county bowling in Worcestershire’s cause consider that his best days for England are still to come. As he grows in confidence and experience in the Test sphere, England could find themselves with one of the finest all-rounders in post-war cricket.