In the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack 2014, John Westerby examined the perils and pitfalls of fielding at short leg.

This article first appeared in the Wisden Almanack 2014.

The landscape around Tombstone, Arizona, is as bleak as the name suggests. These are the barren expanses of cowboy country, an hour’s drive north of the Mexican border. On the way out of town, towards the desert, the signs direct you to Boothill Graveyard, home to so many who died “with their boots on”, slain in the shootouts of the Wild West.

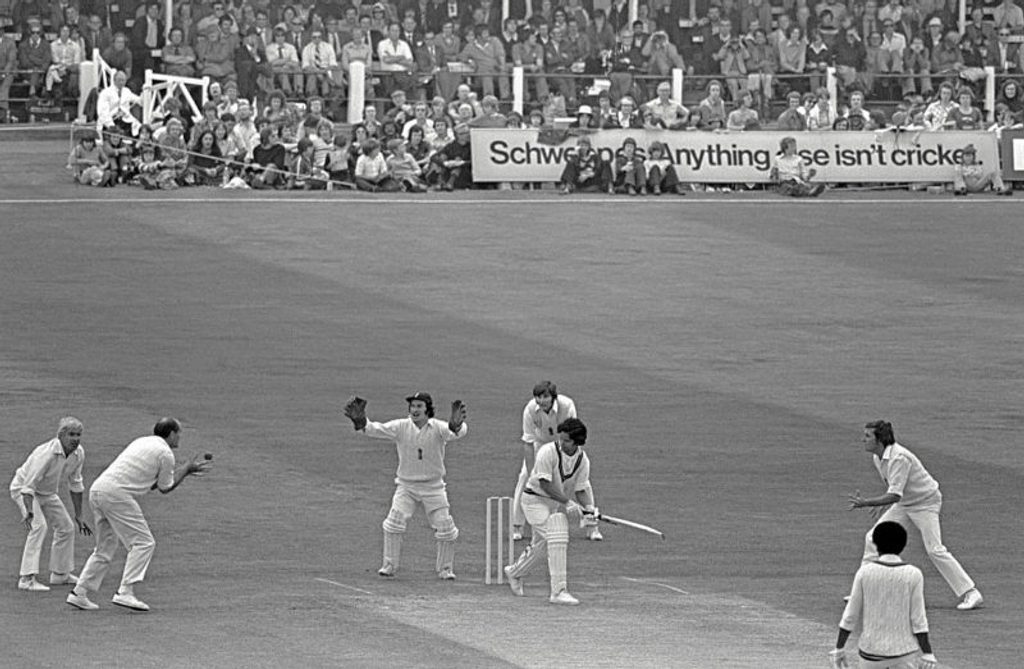

Boothill is the godforsaken spot where no one chooses to end their days – and the name appropriated by English county cricketers condemned to crouch at short leg. The boots are white and spiked, rather than shin-length and caked in dust, but the implication is the same: the unfortunate shoved into the firing line risks perishing with them on. To borrow from Gunfight at the OK Corral: “Good men and women live in Tombstone. But not for long.”

Such has been the reluctance to field under the helmet that the job has traditionally gone to the junior pro, chosen for being disposable, not necessarily well-qualified. In the days of the gentlemen-players divide, there was a feeling that the professional was more likely to draw the short straw, especially if the bowling was unreliable. Yet can this convention survive in our more meritocratic times? And is short leg still such an unappealing prospect?

Keaton Jennings has recently starred for England at short leg

Keaton Jennings has recently starred for England at short leg

When Alastair Cook became England Test captain in 2012, he enjoyed some predictable perks, including a pay rise and an unofficial say in selection. He could also safeguard his physical safety, having for some time been the team’s short leg. Cook moved to first slip, and into his shin pads stepped Ian Bell, who had successfully fielded there earlier in his career. It may be true that, at any level of the game, the cordon tends to be the domain of senior players. But this was not a case of the captain ushering an underling towards the bullets. It now made strategic sense for Cook to take in the broader view from slip. Nor was Bell the junior pro: he was simply the best short leg available.

In modern international cricket, with players’ fielding contributions analysed forensically, the position is filled more and more by specialists, rather than by lambs thrown to potential slaughter. The value of a good short leg has also shot up with the advent of DRS: pad-play is less advisable, bringing the inside edge more into the game.

Yet there is still a sense in which the short-leg fielder is the poor relation: more chances go to slip, so the safest catchers are stationed there. The best all-round fielder will probably stand at backward point. But short leg must be chosen with care. Richard Halsall, who was appointed England’s first full-time fielding coach in 2007, explains the selection process. “There are positions that take priority, and top of the list are first and second slip,” he says. “You’re not likely to put a bowler at short leg, because it doesn’t make sense for him to be crouching so much. So invariably it’s a batsman who isn’t fielding at slip. But he’s got to be good. He’s got to be brave, an outstanding catcher and, ideally, a good reader of the batsman.”

Anticipation is key to being a good short-leg fielder

Anticipation is key to being a good short-leg fielder

After taking a reflex short-leg catch to dismiss West Indian tail-ender Corey Collymore at Old Trafford in 2007, Bell wrote that the key lay in picking up clues from the batsman’s body language, while keeping one eye on the ball. Being a batsman helped him decipher the gestures. And so did the bowler’s accuracy – Monty Panesar in this case – which Bell said allowed him to stay on his toes; fear of a long-hop would drive him back on to his heels, making him less primed to pounce.

Yajurvindra Singh, the Indian batsman who on his debut against England at Bangalore in 1976-77 equalled Greg Chappell’s Test record of seven outfield catches in a match, has spoken of the importance of staying close to narrow the angles, and of taking the ball behind – rather than alongside – you to gain a fraction more time.

There is, then, a high degree of skill involved, yet a move into the slips is still regarded as a promotion – though one based these days as much on ability as seniority. The evidence was there again in Australia in 2013/14, where Graeme Swann’s retirement meant that Bell, despite his prowess at short leg, was whisked into the slips. Joe Root had been groomed as Bell’s understudy, and remains the most likely regular replacement.

This level of planning has not always been in place. When Andrew Strauss first played Test cricket, in 2004, he found himself performing the new boy’s duties under the lid, despite having had no experience there for Middlesex. A couple of fluffed chances meant his short-leg career was short-lived and, while Strauss may not have dropped those chances on purpose, suspicions can arise. “It’s like twelfth man,” says one county coach. “It’s not a job some of them want to do too well in case they get asked again.”

Richard Montgomorie was one of county cricket’s most revered short legs

Richard Montgomorie was one of county cricket’s most revered short legs

Perhaps it will be ever thus. Yet for all the fielders who have served their time at Boothill before graduating to slip, there are plenty who have made the position their own, especially in county cricket. Think of Brian Close’s bloodymindedness, Micky Stewart and Stuart Surridge helping out Jim Laker at Surrey, the vigilance of Peter Walker for Glamorgan, Basharat Hassan’s nimbleness for Nottinghamshire – a quality he handed down to Mick Newell – and, more recently, Richard Montgomerie sniffing out catches for Mushtaq Ahmed during Sussex’s golden run in the 2000s.

These are the players who perhaps made the mistake of doing too good a job. Either that, or they were happy to trade risks to life and limb for an intense involvement in the game. For some, there is undoubtedly the thrill-seeker’s adrenalin rush; for others, the fact that concentration is easier, less optional, when you are one metre from the bat. These are the brave few for whom Boothill is not such a desolate place.

But is it really so dangerous? The answer depends on the quality of the bowling. Watch a short-leg fielder for any length of time, and the perils seem clear enough, especially if the batsman is sweeping. One thing is certain: short leg is a riskier position than silly point. On the off side, there is an extra split second to react, and the ball’s trajectory is more predictable. Yet serious injuries are few and far between. “A lot of people are surprised by this, but you’re actually more likely to get injured in the slips, especially breaking a bone,” says Halsall. “At short leg, you tend to get glancing blows to soft-tissue areas – as long as you get your evasive action right.” The most grisly exception was Raman Lamba, the Indian batsman who died in 1998 after being hit on the temple while fielding at short leg during a club game in Bangladesh.

Knowing how to take evasive action properly is a key skill at short leg

Knowing how to take evasive action properly is a key skill at short leg

Protective equipment is more advanced than in the days when Close would, unflinching, take a blow to the forehead, and watch with grim satisfaction as the ball looped to Phil Sharpe at slip, which is how Martin Young was dismissed at Bristol in 1962. Shin pads are now commonplace, while helmets have bigger grilles, throat protectors and an extension to cover the nape of the neck when the fielder turns his back. Close, of course, chuckles at the equipment worn now. “I only remember feeling pain if we lost the game,” he says. And he was one captain who made a point of stationing himself, rather than a team-mate, under the batsman’s nose.

Even Close, though, recognised the importance of taking the appropriate evasive action. The instinct on seeing a batsman’s backlift is to jump up and away. But England’s coaches have reasoned that the “down and in” technique is more effective. “You make yourself as small as possible, put your head down and bring your hands into your chest, like the brace position,” says Halsall. “That way, your helmet and shin pads are the target. If you jump up and turn your back, you’re exposing quite a few vulnerable areas, like the back of your legs.”

Montgomerie remembers a full-blooded pull on to his hip from Shane Watson: “That wasn’t pleasant. But the one time my confidence took a knock was fielding against Kevin Pietersen at Horsham. I didn’t get hit, but he chose where he wanted to place the ball, and he had the skill to do that, almost irrespective of line or length. That made him really difficult to read.”

Pietersen was tough to read as a short-leg fielder

Pietersen was tough to read as a short-leg fielder

While Close was the reflex fielder nonpareil, for reasons of bravado as much as skill, Montgomerie knows short leg more intimately than anyone. He learned the ropes at Northamptonshire in 1995, when Anil Kumble took 105 Championship wickets from nearly 900 overs, and Montgomerie’s catching accounted for 17 of them. When he moved to Sussex, he played an integral role in the success enjoyed over six seasons by Mushtaq Ahmed. He may well have reached the 10,000 hours that author Malcolm Gladwell argued was a benchmark for mastery of a subject.

“I spent a long time at short leg, and I’ve got the dodgy hips to prove it,” says Montgomerie. “You learn more about the position the longer you spend there. I stood two or three feet squarer at the end of my career than I did at the start, with my right foot on the crease to a right-hander. You learn to come closer if the pitch is dead, to stand back if it’s bouncing. You’re there for the bat-pad, really. Anything else is a bonus.”

The bonus catches, inevitably, are the ones Montgomerie recalls most fondly, especially the three he took from full-blooded sweeps. “The one that really sticks in the mind is Middlesex’s Ben Hutton off Mushy at Horsham in 2006. I anticipated the lap-sweep, moved behind square as it was being played, and dived to take the catch.” Like most short legs, Montgomerie was originally sent to Boothill because he wasn’t good enough in the slips. “I dropped a sitter there with Northants,” he says. “So I soon found myself at short leg. I actually enjoyed it.”

Brian Close is one of the iconic short-leg fielders

Brian Close is one of the iconic short-leg fielders

When Halsall became England’s fielding coach, he picked Montgomerie’s brains: “He’d been sensational in there for Sussex, muttering under his breath, helping Mushy create that claustrophobic feeling, and taking some incredible catches. He made a difficult job look simple. Most of all, he made it look fun.

“But Ian Bell has been as good as anybody in the world. He loves learning about the game, and reads batsmen brilliantly. There have been some good close fielders: Ponting at silly point to Warne, Jayawardene to Murali. But Belly has been just as good. One catch he took to dismiss Hamish Rutherford off Monty Panesar at Wellington in 2013, diving low to his right at backward short leg when Rutherford turned one off his hip, was as good as it gets.”

Perhaps one day he will host a convention for downtrodden, underappreciated short-leg fielders everywhere. If he does, there is a graveyard in Arizona that would make the perfect location.