The 2016 edition of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack paid tribute to the life of one of Australia’s all-time great opening batsmen, Arthur Morris.

Morris, Arthur Robert, MBE, died on August 22, 2015, aged 93

*Maddocks died in 2016

Read more from the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack archive

In the decade immediately following the Second World War, left-hander Arthur Morris vied with Len Hutton for the title of Test cricket’s best opening batsman. Strong on the back foot, he was the leading scorer for Don Bradman’s 1948 Invincibles – when his 696 Test runs trumped even the Don (508). By the end of the series Morris’s average was 74 and, if that tailed off a little, he remained a heavy scorer – and an immensely popular teammate and opponent.

By nature he was an artistic batsman, although he could also be destructive. Jack McHarg’s biography was subtitled An Elegant Genius, but the English journalist Denzil Batchelor wrote: “Strange that one so essentially pink and cherubic should wield a bat with so richly a basso voice. Arthur Morris should, from the look of him, be a caresser of leg-glides, a fingerer of porcelain-fine late cuts; instead he is the author of weighty pulls worthy of a whole fleet of Volga boatmen, and a driver of proconsular imperiousness.” Batchelor’s purple prose might have been describing Morris’s onslaught on the Queensland attack to finish a match at Sydney in January 1949 when, instead of a leisurely stroll to a target of 143, he blazed an unbeaten 108 in 82 minutes.

Morris the player and Morris the man were inseparable: John Arlott wrote that he was “one of the best-liked cricketers of all time – charming, philosophical and relaxed”, while Gideon Haigh referred to him as “the acme of elegance and the epitome of sportsmanship”. In conversation, Morris was generous to his fellow players – self-deprecating, but obviously delighted by the satisfaction cricket had afforded him, even if its material legacy was, in his own word, “poverty”.

One of his favourite accounts was of the Oval Test of 1948, when Bradman’s duck overshadowed all else. Eyes twinkling, Morris would tell of enlightening a questioner that, yes, he had indeed been at The Oval that Saturday afternoon. And, yes, he had actually been batting at the other end when Eric Hollies did for the Don. When pressed, he would confess to having scored 196. Around this time, such was Morris’s dominance that Bradman might have echoed WG Grace – an admirer of Arthur Shrewsbury – by saying “Give me Arthur” as a measure of his value. Although Bradman tempered the praise with a reminder that “he wasn’t always straight in defence”, he immediately qualified it with “but this was merely a sign of his genius”.

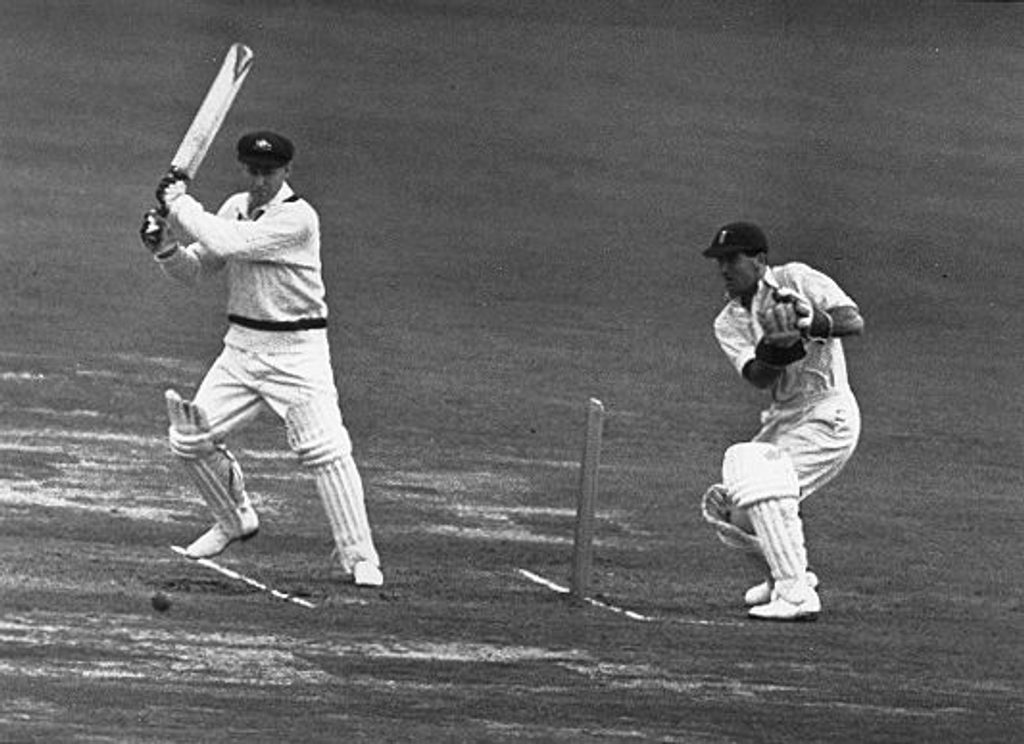

Morris was the leading run-scorer in the 1948 Ashes series

Morris was the leading run-scorer in the 1948 Ashes series

***

Morris was born in the Sydney seaside suburb of Bondi in January 1922, but his family soon moved to the small country town of Dungog, near Newcastle, following the transfer north of his father, a teacher. His English-born mother left the marriage, so Morris had the unusual experience for that time of growing up mainly in the care of a single father. When they returned to Sydney, he was educated at Canterbury Boys’ High School, which later produced a cricket-loving Australian prime minister in John Howard, and the cricket historian David Frith. At school, Morris’s prime strength appeared to be as a dispenser of left-arm unorthodox spin, with tennis and rugby union completing a trio of sporting accomplishments.

He turned out for the St George first-grade side at the age of 14. Their legendary leg-spinner, the bluff Bill O’Reilly, directed him to forget the childish baubles of spin – despite a recent haul of 55 wickets at five apiece in an Under-16 competition – and concentrate on becoming an opening batsman. Morris followed this advice so well that, in his first match for New South Wales, in December 1940, aged 18, he scored 148 and 111 against Queensland at Sydney, to become the first to make twin centuries on first-class debut. When “Doc” Evatt, later president of the United Nations General Assembly and leader of the Australian Labor Party, heard that Morris had made his runs using a borrowed bat, he sent him to Stan McCabe’s shop in Sydney to choose a new one.

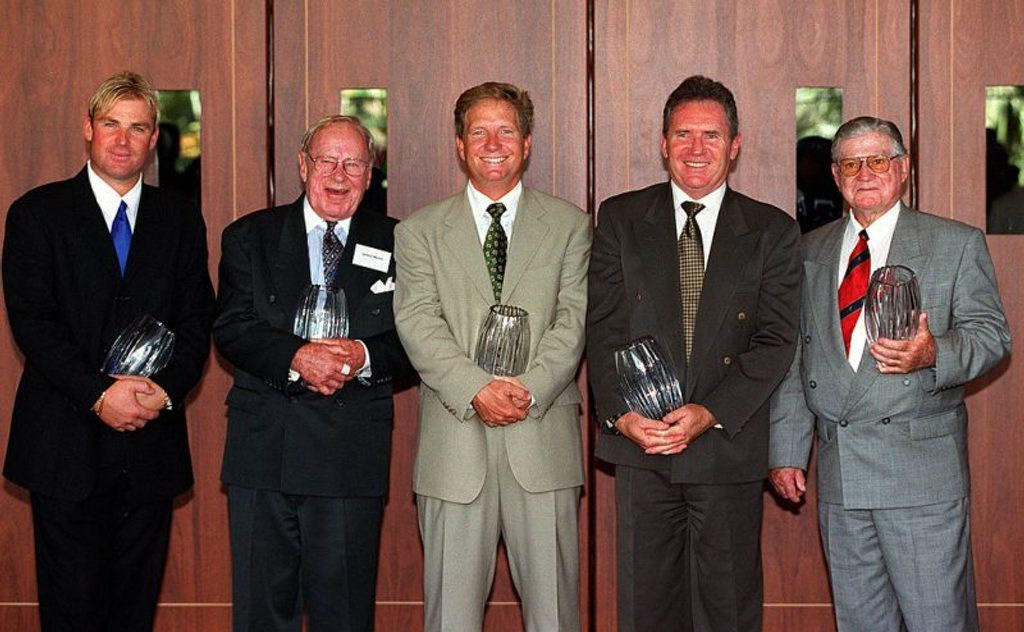

Morris (second from left) was named in the Australia team of the 20th century

Morris (second from left) was named in the Australia team of the 20th century

After three years’ service in Papua and New Guinea with the Australian army, Morris returned to first-class cricket in 1946/47. He started in rich touch, scoring runs for fun, except in his first two Tests, against England: he made two and five, then 21 in the first innings of the Third Test at Melbourne. But, in the second, he removed any question marks with six hours of concentration and care, putting the match virtually beyond the reach of Wally Hammond’s side with 155. Morris added a century in each innings of the next Test, in stifling heat on a country road of a pitch in Adelaide.

The Ashes tour of 1948 found Morris at his best. He amassed 1,922 runs at 71, and Australia won 4-0. Wisden selected him as one of the Five Cricketers, praising an “air of complete composure”, and adding that “he combines unusual defensive qualities with the ability to decide early in the ball’s flight what his stroke shall be”. At Headingley, it was Morris who propelled the last-day chase of 404, protecting Bradman when Denis Compton’s tweakers were causing him anxiety, and hitting him out of the attack. His 182 took only 291 minutes, while his partnership with Bradman produced 301 for the second wicket in only 217. His long Oval innings was a more sedate affair, lasting 406 minutes – but it ensured England would pay dearly for collapsing for 52 in their first innings.

Morris and Hutton were the two great opening batsmen of their era

Morris and Hutton were the two great opening batsmen of their era

Morris’s 196 set up an innings victory, which also meant Bradman did not have another chance to lift his average back into three figures. After a fruitful series in South Africa in 1949/50, Morris’s seasons of plenty grew fewer, his favourite opening partner Sid Barnes having fallen foul of the selectors. During the 1950/51 Ashes, the perception of Morris as the bunny of his close friend Alec Bedser was reinforced. After Morris fell to him four times in his first five innings, Bedser handed over a copy of Lindsay Hassett’s Better Cricket, with the sections on batting underlined in red.

Morris scored 206 in the next match at Adelaide – the highest of his dozen Test centuries – and returned the book with the sections on bowling similarly highlighted. It is true that, in 21 Tests against each other, Bedser dismissed him 18 times – but, Morris would politely point out, he averaged more than 50 against England overall.

He struggled for consistency throughout the 1952/53 series against Jack Cheetham’s South Africans, until the final Test, at Melbourne, where hesitancy was replaced by the old model. He dominated the bowling until he reached 99, only to sacrifice his wicket in a mix-up over a single with the in-form Neil Harvey, who went on to make 205.

Morris was never Australia’s permanent captain, although he did the job twice as a stand-in – both defeats, by West Indies at Adelaide in 1951/52 (the first Test to feature play on Christmas Day), and by England in the Second Ashes Test of 1954/55 at the SCG. Still, he was named in the national Team of the Century in 2000, and the following year inducted into the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame.

During the 1953 Ashes tour, Arthur Morris had gone backstage at the Victoria Palace Theatre, where he met Valerie Hudson, a member of the chorus. Despite his shyness, their relationship developed to the point where he sponsored her migration to Sydney, and they were married in September 1954. She was taken ill with cancer while he was touring the West Indies the following year, but did not tell him until his return to Australia, when he announced his retirement. Financial assistance from Vivian Van Damm, the owner of London’s Windmill Theatre, enabled them to travel back to England to see her family; Morris covered the 1956 Ashes for the Daily Express. Valerie died, only 33, in January 1957. Morris married Judith Menmuir in 1968, a long and happy union.

He spent a long period in the motor trade, then played a significant part in the introduction of tenpin bowling to Australia, before finishing in PR. He remained an honoured guest at cricket grounds everywhere, his dignity never puffing up into pomposity, thanks to an acute sense of the ironic and the whimsical. He was appointed MBE in 1974, and was a member of the Sydney Cricket and Sports Ground Trust for 22 years. Three days before he died, the Arthur Morris Gates were unveiled as a tribute to his long association with the SCG. When his wife asked why he had four gates named after him, he shot back that it was “because I was an opener”.

Morris was the oldest surviving Australian Test player, a distinction that passed to the former wicketkeeper Len Maddocks* – although Harvey, Morris’s friend and team-mate in 35 Tests, was the last surviving Invincible. “You wouldn’t find a nicer bloke in the world,” he said. “A great sense of humour, a great team man.”