Allan Border, who retired in May 1994 as Test cricket’s highest run-scorer, committed the greater part of a long and distinguished career to re-establishing the credibility and image of Australian cricket. A self-effacing man of simple tastes and pleasures, Border served at the most tempestuous time in cricket history, and came to represent the indomitable spirit of the Australian game.

Allan Border was one of the great Australian captains, leading the team from the wilderness to the beginning of a new golden era. After his retirement, the 1995 edition of the Wisden Almanack saluted his achievements.

Allan Border, who retired in May 1994 as Test cricket’s highest run-scorer, committed the greater part of a long and distinguished career to re-establishing the credibility and image of Australian cricket. A self-effacing man of simple tastes and pleasures, Border served at the most tempestuous time in cricket history, and came to represent the indomitable spirit of the Australian game.

As it grappled with two schisms, the first over World Series Cricket, the second over the provocative actions of the mercenaries in South Africa, it was debilitated and destabilised as never before and cried out for a figure of Bradmanesque dimensions to return it to its rightful and influential position on the world stage.

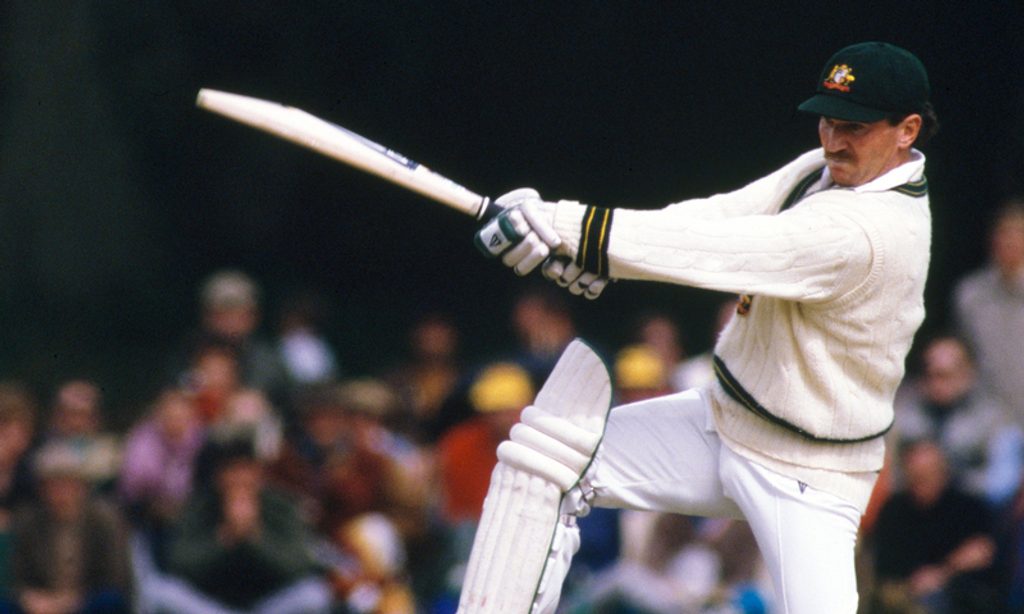

Border retired as Test cricket’s highest run-scorer

Border retired as Test cricket’s highest run-scorer

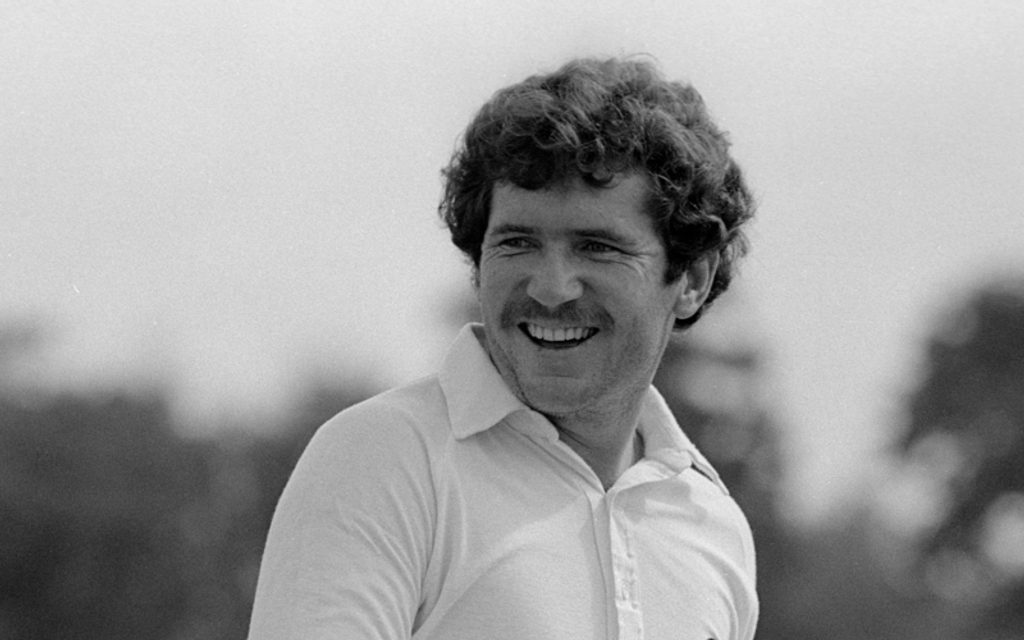

Into the breach strode earnest Allan Robert Border, a working-class boy, born at Cremorne on the north shore of Sydney Harbour, who grew up over the road from the Mosman Oval that now bears his name. At one time he was a beach bum, who was cajoled from his indolence and indifference by the noted coach and former England Test player, Barry Knight. But Border, standing just 5ft 9in, bestrode the Test match arena like a colossus for more than 15 years.

When he retired 11 weeks before his 39th birthday, after fulfilling his ambition to lead Australia in South Africa, Border was entitled to be ranked alongside Sir Donald Bradman as the greatest of Australian cricketers. Certainly no one since Sir Donald has done more to advance Australian cricket throughout the world – particularly in developing countries.

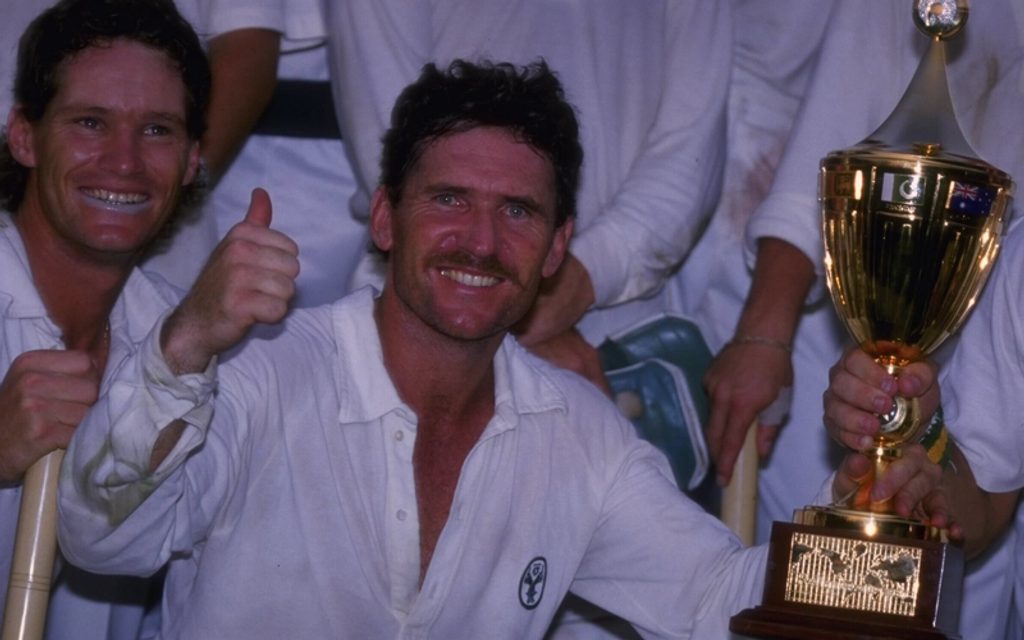

Border’s batting cannot really stand comparison with Bradman, but many of his achievements go far beyond the Bradmanesque – 156 Test matches, 153 of them consecutive, on 36 grounds in eight different Test-playing countries ( Sir Donald played 52 Tests on ten grounds, all in Australia and England); 11,174 runs at 50.56 with 27 centuries and 63 fifties; 93 consecutive Test matches as captain; 156 catches; 273 limited-overs appearances, 178 as captain, including Australia’s victory in the 1987 World Cup final. All of these accomplishments are in a league of their own and some may remain so; Sunil Gavaskar, the only other scorer of more than 10,000 Test runs, doubts that Border’s run record will ever be broken.

Border’s impact for Australia drew widespread comparisons with Bradman

Border’s impact for Australia drew widespread comparisons with Bradman

Yet only in the twilight of his career did Border become even faintly interested in his statistical achievements. Essentially he was an unromantic, uncomplicated but uncompromising workman-cricketer. It is problematical whether Border, unlike Bradman, has ever understood his place in history. He reinvigorated Australian cricket and provided it with stability, direction and enthusiasm; this was the most significant of his many contributions and the one which gave him the greatest satisfaction.

There is a remarkable set of figures to underscore the extent of the stability Border provided. From the time he succeeded his fragile friend Kim Hughes on December 7, 1984 until his captaincy ended on March 29, 1994, opposing countries commissioned 38 captains – 21 of them against Australia. From his first Test, at Melbourne, on December 29, 1978, he played with and against 361 different players.

To gain a true appreciation of Border, it is necessary to examine his formative years in the leadership when his team was scorned and he was disturbingly close to a breakdown. In 1985 when Australian cricket reached its nadir and a collection of leading players defected to South Africa, Border, the least political of men, was dragged into a black hole of depression. He was barely four months into his term of office – while he forgave them, he never forgot the hurt caused by those team-mates who pursued the dollar rather than the dream, and opted to play in South Africa. For a man who placed such store in team loyalty, it was a cruel lesson.

When he retired, Border reflected: “I felt very let down. We were playing in Sharjah and everyone was having a beer and saying that the team was starting to get it together. There was that sort of talk. You feel such a fool when you then read in the paper that blokes you have trusted, who have told you how great the future looks, are going to South Africa.”

Many of his attitudes were formed and much of his philosophy as a captain formulated at this time when Australia were not expected to win and, in the main, did not. The dire circumstances of the day compelled him to think defensively, and it was not until 1989 when he engineered a memorable 4-0 eclipse of a dispirited England that there was a measure of optimism and aggression about his leadership. But while his entitlement to the job was hardly ever questioned, the negativism of his captaincy was the area that most occupied the attention of his critics. In mitigation, he insisted that the circumstances of his time had made it impossible for him to develop a totally positive philosophy.

He evolved into an enterprising captain when he was finally in charge of able and ambitious men, as was evidenced by his thoughtful and often bold use of the leg-spinner Shane Warne. In this period, some English critics felt that Australia’s approach was getting too hard; that might say more about them than about Border.

With customary candour, he often pleaded guilty to periods of moodiness and regretted that, at least in the dressing-room, his instinct was to internalise his deepest thoughts and feelings. Paradoxically, he was an expansive and articulate spokesman, and was much admired by the media for being accessible, courteous and forthright. So he had good reason to resent the Captain Grumpy tag foisted upon him by the tabloids.

With few, if any, exceptions, his team-mates and employers indulged his contrariness; it was infrequent and irritating rather than damaging. Indeed, the fact that his actions and reactions were always so commonplace, so human, made him an endearing as well as an enduring champion. Essentially, he was an ordinary soul who accomplished extraordinary deeds. For a suburban family man, with an unselfconscious hankering for a beer around a backyard barbecue, Border became an exceptionally worldly cricketer. That he was able to expunge many of the prejudices and preconceptions amongst his team-mates about playing cricket in the Third World was another of the outstanding legacies of his captaincy.

Border celebrates after his team beat England in the final of the Cricket World Cup in Calcutta

Border celebrates after his team beat England in the final of the Cricket World Cup in Calcutta

The fact that his technique and temperament allowed him to play productively in the most extreme conditions and situations was perhaps the true gauge of his greatness. Indeed, the tougher the predicament the more resolute and more resourceful was his batting. He averaged 56.57 in 70 overseas Tests. In Australia, he averaged 45.94 in 86 Tests. And he averaged fractionally more as captain (50.94) than as non-captain (50.01) – further confirmation of his red-blooded response to challenge.

While he was never numbered among the poetic left-handers, it is erroneous to categorise him as just an accumulator of runs. In his pomp, he hooked and pulled as well as he square cut and drove in front of point. For many years he was bracketed with Javed Miandad, another eminent and indefatigable scrapper, as the foremost player of slow bowling in the world.

Furthermore, Border was blessed with all-round skills. He was a sure catch anywhere, but especially at slip, and in the limited-overs game earned an impressive reputation for his ability to throw down the stumps from any angle within the circle. And while he was self-deprecating about his left-arm orthodox spin bowling, he once took 11 wickets in a Sydney Test against West Indies. But that was no balm for his disappointment at being unable to defeat West Indies in a Test series and so legitimately claim for Australia the unofficial title of world champion. At Adelaide in 1992-93 he went within two runs of attaining the goal.

His retirement from the captaincy and Test cricket was messy, an unfortunate situation caused, more than anything, by a misunderstanding between Border and the Australian Cricket Board. It should have been done with style. But he handed to Mark Taylor the most precious gift of all – a stable, committed, educated, enterprising and hard-edged elite cricket team. Australian cricket will forever be in a debt of AB, the cricketer’s cricketer, the people’s cricketer and a bloody good bloke with it.