Wadekar, Ajit Laxman died on August 15, 2018, aged 77

The Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack 2019 is the 156th edition of ‘the bible of cricket’. Order your copy now

Read more from the Almanack archive

Ajit Wadekar, who died a year ago, led India to two epic series victories in the early 1970s. His Wisden obituary established his credentials to be considered one of his country’s most significant leaders.

In the second over of the final morning of the decisive Oval Test in August 1971, with India 97 from a first series victory in England, Ajit Wadekar hesitated while attempting a single, and was run out. It left his side three down. Wadekar returned to the dressing room, lay on a bench, and fell asleep. As he dozed, his team carved a niche in the history of Indian cricket: he was woken to be told they had won by four wickets.

Earlier in the year, under his quietly authoritative captaincy, India had won a series for the first time in the West Indies. Now they had shrugged off decades of deference and defeats to win in England. Eighteen months later, they beat them at home to complete a memorable hat-trick: almost 40 years after their first Test, India had announced themselves on the world stage. Wadekar was fortunate to inherit a group purged of factionalism by his predecessor, Tiger Pataudi.

He also came armed with the greatest spin-bowling arsenal the game had seen and, in the Caribbean, was stiffened by the emergence of Sunil Gavaskar. He was cool under pressure and tactically sharp, while a new emphasis on close catching benefited the spinners. “I thought, if I am going to prove to the selectors that they have a proper replacement for Pataudi,” he said, “the only way is to start winning, and outside the country.”

Wadekar was no prodigy: his father thought the game would distract him from a career in engineering, though he did once present him with a new bat after an impressive algebra result. And he became a cricketer almost by accident. While a student at Elphinstone College in Bombay, he shared a bus journey with future Test player Baloo Gupte, who invited him to be twelfth man for the college team. Wadekar was reluctant, but a match fee of three rupees sealed the deal.

His left-handed elegance caught the eye of Madhav Mantri, a former Test wicketkeeper, and his first-class debut for Bombay came in the quarter-final of the 1958/59 Ranji Trophy. In the final, he scored 85 as they beat Bengal.

He was soon joined in a powerful line-up by Farokh Engineer, who remembered: “In those days it was more difficult to get into the Bombay team than the India team.” It was the start of 18 Ranji Trophy wins in 19 seasons for Bombay, with Wadekar taking over the captaincy in 1968/69. He owed the launch of his Test career to Mantri, who persuaded Pataudi his batting would be an asset.

Wadekar made his debut against West Indies in 1966/67, struggled, and was dropped after one game. Recalled at Madras, he began the second innings on a pair but quickly hit Wes Hall for six and four, and justified Mantri’s faith by top-scoring with 67. In England in 1967, despite Pataudi’s enterprising leadership, India lost 3–0. But Wadekar finished second in the averages, having hit 91 as India followed on in the first Test at Headingley.

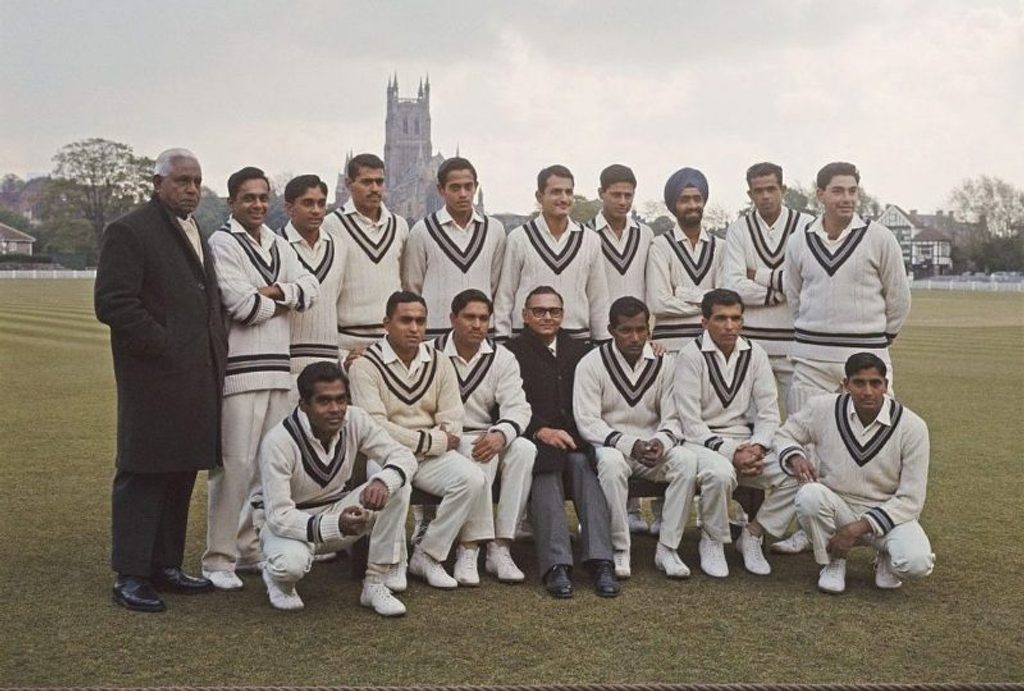

Group shot of the India team in 1967. Wadekar is sixth from left in the back row

Group shot of the India team in 1967. Wadekar is sixth from left in the back row

He was dismissed for 99 at the MCG during another whitewash, in Australia in 1967/68, and when the tour moved on to New Zealand he made 328 runs at nearly 47, scoring 143 at Wellington – his only Test century. “He was definitely a much better batsman than his figures suggest,” said Bishan Bedi.

Wadekar felt his place was in jeopardy for the tour of the West Indies in 1970/71, but instead of the axe he was handed the captaincy. Vijay Merchant, the chairman of selectors, had been left with the casting vote, and opted for Wadekar’s calmness ahead of Pataudi’s charisma. “He thought Pataudi was too flamboyant,” said Engineer.

Wadekar was with his wife, buying curtains for their new home in the State Bank employees’ apartments. When they returned, a crowd of well-wishers and journalists were waiting outside. “My first thought was that some guy in the building had been promoted,” he recalled. “Little did I realise that it was me.”

Ajit Wadekar of Bombay Cricket Club, circa 1964

Ajit Wadekar of Bombay Cricket Club, circa 1964

India left for the Caribbean weakened by the absence of Pataudi, who had withdrawn, and Engineer, left out because he was not resident in India. And they were still haunted by memories of their previous visit, in 1961/62, when they were thrashed 5–0, and terrorised by Hall and (in a tour game) Charlie Griffith. Wadekar was determined to avoid a repeat.

In the first tour match, in Jamaica, he was hit on the hand by pace bowler Uton Dowe, but ignored blood seeping into his glove to make 70. He also introduced a more aggressive approach. In the first Test at Sabina Park, he enforced the follow-on, against the wishes of his batsmen, who wanted more time in the middle as the game headed for a draw. “I went straight to the dressing room and said it a bit loudly: ‘Garry [Sobers], I think you are batting. I am enforcing the follow-on.’”

India won the second Test by seven wickets, their first victory over West Indies at the 25th attempt. Thereafter, quicker pitches were prepared, but India – with Gavaskar averaging 154 and Srinivas Venkataraghavan taking 22 wickets – were not to be denied.

There was an ecstatic welcome at Bombay airport, and an audience with prime minister Indira Gandhi, but many felt the forthcoming trip to England would provide a sterner test of India’s new self-esteem. Two key decisions were made: Engineer came out of temporary exile to be Wadekar’s vice-captain, and leg-spinner Bhagwat Chandrasekhar was recalled.

The Indians won five of their eight warm-up matches before the first Test at Lord’s. After beating Hampshire at Bournemouth, they arrived in London to find themselves booked into a fly-blown hotel. Wadekar struck an important blow for esprit de corps by successfully demanding better accommodation.

He made another statement on the second day of the match, hooking John Snow fearlessly on his way to 85, the highest score of the Test. “From the moment he came in, Wadekar mounted a stirring counter-offensive, driving, hooking and cutting,” wrote John Arlott in The Guardian. Rain ended play on the final afternoon, with India, eight down, needing 38. At Old Trafford, the weather spared them almost certain defeat, so it was 0–0 going to the final Test at The Oval. Again, India struggled, conceding a first-innings deficit of 71, but Chandrasekhar took 6-38 to turn the match in their favour.

It had been a triumph for the undemonstrative leadership qualities Merchant had divined. “He didn’t make big speeches and I don’t recall him ever giving anyone a big bollocking,” said Engineer. The emphasis on fielding proved crucial. “We hardly dropped any catches in the West Indies and in England,” Wadekar recalled. “After batting in the nets, I used to get fielding and catching done for one or two hours. I saw to it that the specialist fielders trained properly. I was a good slip fielder and I knew exactly the kind of anticipation and reflexes you require.”

And he struck up a fruitful relationship with his deputy. “We had a really good rapport,” said Engineer. “We did not really have to talk about bowling changes and field placings.”

After Wadekar’s death in 2018, the touring Indian players wore black armbands in England

After Wadekar’s death in 2018, the touring Indian players wore black armbands in England

Victory in England increased interest back home, and the visit of Tony Lewis’s side in 1972/73 was eagerly awaited. England won the first Test, at Delhi, but India fought back to claim the five-match series 2–1, Chandrasekhar and Bedi sharing 60 wickets. From that high point, Wadekar’s fall was swift. On India’s return to England in 1974, they were thumped 3–0, including 42 all out at Lord’s, and – having led them in their first ODI – he lost the captaincy. An innings defeat at Edgbaston proved his final Test, and he played just one more first-class match. Memories were short: a giant bat erected in Indore to commemorate the 1971 wins was defaced, and stones were thrown at Wadekar’s Bombay home.

He returned to his career in banking, but in the early 1990s proved a success as India’s first permanent head coach, and also had a spell as chairman of selectors. “For me, he was always ‘captain’,” said Gavaskar. When news of his death reached the Indian touring team in England in 2018, the players wore black armbands during the third Test at Trent Bridge.