Sydney Barnes may have been the greatest bowler in history, but he could also be a difficult man. In the 2012 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Peter Gibbs recalled a day in his company.

Jack Ikin stood on the footplate of the team bus scanning the road ahead. Once of Lancashire and England, now – in the summer of 1964 – captain of Staffordshire, he seemed unusually agitated as we drew alongside a tall, lean figure waiting at the kerb. The morning had begun damp and murky, and the man wore a black Homburg and a dark overcoat more suited to a February funeral than a day in late summer.

As a small boy I had seen SF Barnes once before, when he bowled the honorary first ball in the match between the 1953 Australians and a Minor Counties XI at the Michelin Works Ground in Stoke. He was 80 at the time, but declined the new ball in case he induced a collapse. My only previous recollection of him had been a photograph in The Book of Cricket, written in grandiloquent style by Denzil Batchelor. I would guess he was in his seventies when the photo was taken, and judging by his expression he found the experience sorely trying.

Former England cricketers Wilfred Rhodes (left) and Sydney Barnes circa 1951

Former England cricketers Wilfred Rhodes (left) and Sydney Barnes circa 1951

Posed against chicken wire in what appears to be his back garden, his stern hatchet face is partly shaded by a cap. With a cricket sweater pulled perfunctorily over his shirt, tie and grey flannels, he glares into the lens, his right arm fixed at the perpendicular, a ball cocked in his fingers. While lionising Barnes’s feats, Batchelor was less effusive about the man himself. That he was demanding company was something I was about to discover at first hand.

“Sydney’s come for a day out,” said the skipper. “I’d like you to look after him. It’s not every day you get a chance to impress one of the greats.” Being the junior member of the team might have had its advantages, but I sensed this was not one of them. Cardus said of Barnes that “a chill wind of antagonism blew from him on the sunniest day”, having already affirmed: “There was a Mephistophelian aspect about him.”

Undoubtedly SF’s attitude became part of his stock-in-trade, reinforcing his image as the batsman’s bogeyman. Even Harry Rutherford, the painter of the portrait which hangs outside the home dressing room at Lord’s, confessed to feelings of apprehension when confronted by his subject.

On our arrival at Walsall, where we were due to play Bedfordshire, Ikin introduced me to SF as an “opening batsman and recently dubbed Oxford Blue”. The old boy reacted as if he had been asked to accommodate a scorpion in his pants. Observing his response, the skipper added that I also played for Norton in the more prosaic surroundings of the North Staffordshire League. “Peter will get you what you need, Sydney,” he said, and withdrew with an anxious smile.

“Norton?” said SF. “Yes.” “Worrell, Laker, Sobers.” He reeled off the club’s roll call of professionals. A slight softening in his eyes suggested this was the calibre of players he could readily relate to. “Frank Worrell, fine player. Fine man. Laker? Those pitches in ’56 were a travesty. Money for old rope. What did he do in Australia?” His gimlet eyes searched my face for the answer. “Not much?” I hazarded. Of SF’s 106 Ashes victims, 77 had been bagged on plum Australian pitches. “Nobody got all 10 when I was bowling at the other end,” he chuntered.

I could hear the clink of cups and saucers inside the pavilion. “Would you like a coffee, Mr Barnes?” But he was lost in deliberation. “Sobers I like. Batting or bowling, he attacks. That’s the thing – attack, attack. A gamble, of course, for a left-hander against someone like me.” Holding an imaginary ball, SF sketched three deliveries with a flick of his long fingers – the first two pitching and beating the outside edge, the last breaking the other way through the gate.

“I think he’s taken a shine to you,” said the skipper as I queued for coffee. I rather doubted it. I had heard the cautionary tales bequeathed by “Barney’s” Staffordshire and league club contemporaries. Cricket was his occupation and he applied himself ruthlessly to it. Anyone not “pulling their pound” met with his icy disapproval. He was paid by results, he would remind them, and those who compromised his efforts through incompetence would be held accountable for any shortfall in the collection box.

During 42 years with Warwickshire, Lancashire and Staffordshire it was SF’s ability to prosper by way of performance bonuses that made him blasé about playing at Test level, where he believed the pay did not match his skills or the demands on his physical resources. After taking part in only seven first-class games over eight seasons, Barnes had been plucked from the Lancashire League to tour Australia in 1901/02 under Archie MacLaren. He was quick to stamp his quality as a bowler on the opposition and his acerbic personality on his fellow players. Speculating on their chances of surviving a storm en route to Australia, MacLaren famously comforted one of his men with the words: “If we go down, at least that bugger Barnes will go down with us.”

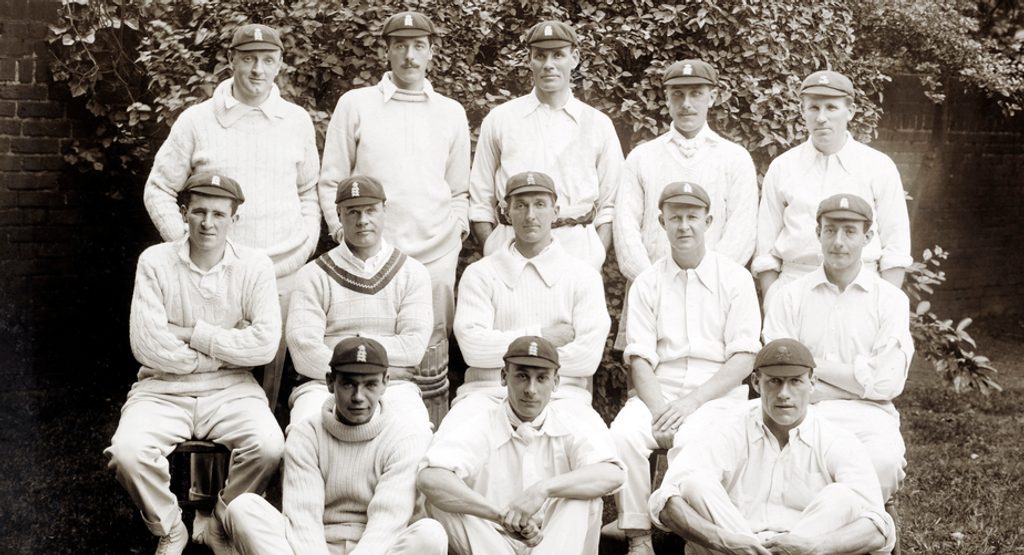

SF Barnes (back-centre) with the England team that regained the Ashes in 1912

SF Barnes (back-centre) with the England team that regained the Ashes in 1912

At the time, Barnes was 28, single, and living in Smethwick with his parents and siblings in an industrial ghetto bounded by a foundry, a gasworks, the railway and the canal. His father worked for the same metal-bashing company for 63 years, and SF made an early decision not to follow in his footsteps. While acknowledging his father’s steadfastness in bringing home the family bacon, he saw how a lifetime’s servitude went unrecognised by the bosses. Whatever Sydney Francis Barnes was destined to be, he would not bow or scrape or accept payment for less than he thought he was worth. In this he was a man more than half a century ahead of his time.

There could be no doubting the affront this attitude caused to the gentlemen amateurs who ran cricket. After two triumphant Tests in his first series, in Australia, before picking up a leg injury, he was excluded from all but one Test in the 1902 Ashes at home. His contractual negotiations with Lancashire were no more cordial and, at the end of 1903, his County Championship career came to an abrupt end. In fact, what appeared to be the sudden rise and fall of a temperamental genius was only the prelude to the Sydney Barnes story.

The woman serving the coffee stirred sugar into the cup and held on to the spoon as if it was an item from Walsall CC’s trophy collection. “Biscuit, love?” Without waiting for a reply she slipped a Rich Tea into the saucer. I had already watched her overfill the cup, and the possibility of spillage induced fresh waves of anxiety. My brief scrutiny of SF had taken in his highly polished shoes, his pinch-perfect tie, a pin behind the knot neatly anchoring the tips of his collar. He was a stickler, no doubt about it. Soggy biscuits a no-no.

“Don’t I get a spoon?” “It’s been stirred.” “Huh.” “The lady’s only got one spoon,” I added, to dispel any suggestion of the 91-year-old being incapable of stirring it himself.

“Batsman?” he said after a pause. “Yes.” “Oxford?” “Yes.” “Blue?” His voice had a dark, accusing tone. I was eager to make clear I was no gilded youth but a product of state schooling and league cricket, just as he had been. In the interests of establishing a rapport I even considered owning up to the type of bloody-minded obduracy and truculence he had made his trademark. But I could sense he had already made up his mind. I was a jazz hat. A man of private means. A dilettante.

“How’s the coffee?” “Wet.” “I’d better go and get changed.” “’Ere, take this biscuit. You need building up.” The summer of ’64 had been blighted by a developing La Niña (El Niño’s colder sibling), and pitches were suffused with moisture. Having won the toss, Bedfordshire chose to bat, but within four overs the palliative effect of the roller had worn off and the ball was taking divots out of the pitch. At lunch, they were 65-7. The skipper asked me to usher SF into the club room, where he was to sit between the two captains.

The England team on their 1901 tour of Australia, (Barnes back row, fourth from left)

The England team on their 1901 tour of Australia, (Barnes back row, fourth from left)

“Not Spam, is it?” he enquired warily. “Ham salad, I think.” He pushed down on his stick and rose from the bench seat. I stayed close, but my concerns about his mobility were misplaced. Square-shouldered as a tailor’s model – in the words of Alan Ross – he took his place as if of right at the head of the lunch table. Given the score it is doubtful if he thought it necessary to offer advice to Ikin during the interval. But from 90-8 the ninth-wicket pair opted for a hit-or-miss strategy. With fortune smiling, as it so often does on tailenders having a lark, they pasted our bowling to all parts in a stand of 108, enabling a tea-time declaration at 204-9. One can only imagine SF’s reaction to such a hapless surrender of advantage.

Yet if he had one soft spot, it was for his native county. Renowned though he was for changing league clubs for better terms, he remained loyal to Staffordshire for more than 30 years. There he enjoyed a standard of cricket he could dominate without undue effort, and a committee that indulged his every whim. In his own backyard, the celebrated match-winner could put gentleman captains in their place according to merit, which naturally was much inferior to his own.

Between times, “if the money was right”, he accepted invitations to play in representative games and Tests. In this way he shrewdly husbanded his physical resources. Too many professional cricketers, he observed, were doomed on retirement to manage “fourth-rate beer houses, trading as best they could upon their faded glories”. Remarkably, not only was he fit enough to pro into his sixties, but by training to be a calligrapher he also ensured employment well beyond his playing days.

Once SF had sat down for tea the skipper relieved me of my duty so that I could pad up and compose myself. It was not long before I was back in the hutch for nought, undone by a loosener that spat off the track, smacked me on the gloves and ballooned to gully. Such was the speed of my entrance and exit, I thought there was a chance SF would still be in the club room. But he was back on the bench, puffing at his pipe and missing nothing.

My period of mourning proved as brief as my stay at the crease. The changing-room condolences had barely begun when I was handed a bunch of scorecards by our No. 4. He was playing on his home ground and had been asked by kids in the club’s junior section to get them the autograph of the “famous old bloke”. He would have asked himself, he claimed, but he was next man in. Given SF’s prickly reputation, I folded the scorecards inside a newspaper in order first to gauge his humour. He had always been quick to rebuke and just as swift to take offence.

When amateur captain JWHT Douglas decided to take the new ball himself rather than give it to Barnes at Sydney in 1911/12, SF’s display of sulking was obvious. “He was good with his fists so he was spoiling for a fight,” SF told me matter-of-factly, alluding to Douglas’ Olympic middleweight gold medal in 1908. “He wanted to put me in my place, but I wasn’t drawn.”

SF’s disinclination to refer to my rapid journey to the crease and back I put down to indifference rather than polite regard. The ritual emollient of “bad luck” would not have gone amiss, but I was not averse to drawing a veil over my big fat zero. In any case, the early ejection of a batsman was hardly a novelty to a man who routinely put the skids under entire sides. At Melbourne in 1911/12, he produced an opening spell of 11-7-6-5 on a blameless track. Now he was on hand to witness another procession as we slumped to 57-7. In the middle, our batsmen were using the backs of their bats like frying pans to slap down divots and level craters. It was the sort of pitch to make the old boy salivate.

“Would you mind signing these scorecards for some of the junior members?” SF frowned at me, then at the batch of cards. “Have you a pen?” Encouraged, I produced one. “A biro? Never touch them. An Oxford man should have a fountain pen.” Even into his nineties, SF’s skill as an inscriber of legal documents was still in demand. Seven years earlier he had presented a handwritten scroll to the Queen to commemorate her visit to Stafford. Giving him a biro was like asking Yehudi Menuhin to play the ukulele. I found a proper pen and, after he had signed the cards, he returned them with enough of a smile for me to brave further reproaches.

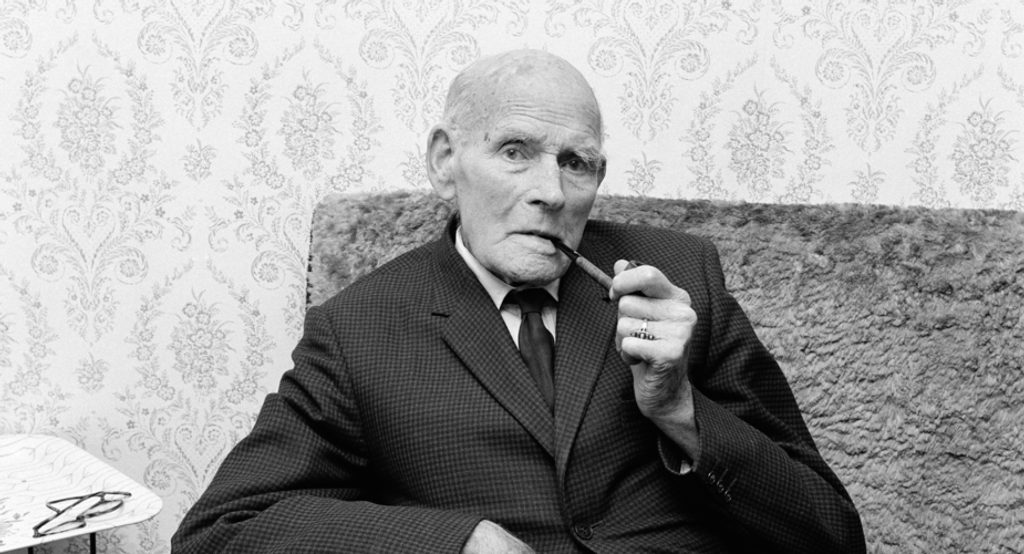

SF Barnes pictured in 1965

SF Barnes pictured in 1965

“The bowlers might like to roll this pitch up and take it with them?” I ventured. “They need all the help they can get. Cricket’s a batters’ game. Always has been.” Anyone perusing SF’s figures might think otherwise. His 719 first-class wickets (189 in Tests) were captured at an average of 17.09. His 1,441 wickets for Staffordshire cost less than half that, and his 4,069 league victims barely six runs apiece.

“Even so, an ideal pitch for cutters?” I persisted. “Possibly. I was a spinner, not a cutter.” His expression had clouded again at my apparent confusion. There was no classification in my MCC coaching manual for a fast-medium spin bowler, though I had heard how he made the ball swerve in the air before bouncing and breaking sharply either way.

The patented Barnes Ball was the leg-break delivered at pace and without rotation of the wrist. It was at its most potent on the matting tracks of South Africa when, at the age of 40, he took 49 wickets in four games, still a record for a Test series. Fielders at mid-off and mid-on reported hearing the snap of his fingers as he bowled, the batsmen unable to read which way the ball would break. In that respect he was the Ramadhin or Muralitharan of his day. But whereas they were spinners using a front-on action and freakish articulation of the arm, SF’s spin was derived purely from the twist exerted by his fingers rather than through leverage of the wrist or elbow. In his opinion the cutter, delivered when the bowler drags his fingers down the side of the ball, was a much inferior cousin.

In the middle, wickets continued to fall. The scoreboard read 68-7; the pavilion clock showed ten past six. Butterflies began to flutter in my guts with the realisation that we were unlikely to avoid the follow-on. Subtracting the time allowed between innings, our last three men had to survive only 10 more minutes to prevent us from having to bat again before the close. SF slid a silver Hunter from his waistcoat pocket. Cradled in his capacious hand, it looked the size of a sixpence. He read the time, sniffed the air and, without a sideways glance, gave me the benefit of his wisdom. “Better get your pads on.” Immediately, batsmen eight, nine and 10 fell without change to the score.

Bedfordshire’s Trevor Morley had returned 7-23. His feat took me back to 1953, when I had seen SF bowl that first ball at Stoke. In the first innings of the match Ray Lindwall had shot out seven batsmen for 20. A coincidence perhaps, or was Barnes’ Mephistophelian aura still spooking batsmen from beyond the boundary?

Sweating on a pair and with a nasty five minutes to survive, I felt more jittery than usual. Though there had been no rain since the start of play, the pitch had still not dried. In the area just short of a length it was dinted like a sheet of beaten copper. I pushed forward defensively to my first ball and was relieved to meet it in the middle of the bat. The second landed in virtually the same spot, but this time leapt vertically, hit the shoulder of my bat and dollied to second slip.

The gloaming had descended prematurely and, though the lights of the clubroom glowed brightly, SF remained a shadowy figure under the lee of the pavilion veranda. My cheeks burned with rage and humiliation at registering the first and, as it would turn out, only pair of my career. I kept my head down until I reached the pavilion steps. Only then did I steel myself to look at him, but his eyes were fixed ahead, fingers wound round an imaginary ball, his mind still scheming to destroy better batsmen than me.