In issue five of The Nightwatchman, Rod Edmond sees parallels in this winter’s Ashes tour and that of 1958-59, when another supposedly fiery attack was put in the shade by the host’s quicks.

This article appears in issue five of The Nightwatchman. Available in print and digital editions.

The Nightwatchman is Wisden’s quarterly. Combining brilliant writing and beautiful design, it is the perfect gift for cricket fans. Take a look at our products and subscription options and for a limited period get 10% off by entering the coupon code NY10 at the checkout*.

*Offer excludes postage and packaging and rolling subscriptions.

Somewhere in the archives is a photograph of five sharp-suited England fast bowlers threateningly posed on the deck of the Iberia as it docked at Sydney. The year is 1958 and the five well-dressed hoods looking for action are Trueman, Tyson, Statham, Loader and Bailey. They were the intended spearhead of Peter May’s team as it sought to win a fourth consecutive Ashes series. This photograph, coincidentally or not, was recreated on the cover of a recent issue of All Out Cricket.

James Anderson, tossing a cricket ball in his right hand, heads a phalanx of similarly besuited quickies: Finn and Rankin to his right, Tremlett and Broad to his left. These menacingly tall figures are to lead the attack of Alastair Cook’s team as it also seeks to win a fourth consecutive Ashes series. In both cases these formidable-looking combinations proved to be mere sheep in lion’s clothing.

I began thinking about the parallels between the Ashes tours of 1958-59 and 2013-14 while watching England’s double collapse in the second innings of the recent Melbourne Test (65-0 to 87-4, 173-5 to 179 all out). It brought vividly to mind the first Ashes Test I ever saw, at Melbourne Cricket Ground, 31 December to 5 January 1958-59. Trailing by 49 runs on the first innings, England collapsed for 87 in their second, destroyed by the pace of Ian Meckiff, the swing of Alan Davidson, and some superb close-wicket catching.

Mitchell Johnson picked the 2013-14 Ashes as one of his career’s best moments

Mitchell Johnson picked the 2013-14 Ashes as one of his career’s best moments

I was 12 years old. My father, a cricket nut, had brought our family from New Zealand to see the second and third Tests. We’d crossed the Tasman by ship, the family car stowed in the hold, and on disembarking at Sydney we immediately hit the road for Melbourne to get there in time for the start of the second Test. I’d seen three Test matches in my life to that point, each of them at Eden Park, Auckland: New Zealand playing South Africa in 1954, England in 1955, when New Zealand made the lowest-ever Test innings score of 26, a catastrophe that was in no way compensated for by seeing New Zealand’s first-ever Test victory against the West Indies the following year, and something which has haunted me ever since. Eden Park in the mid-1950s had two small wooden stands, a members’ stand with the pavilions underneath and a slightly larger one where my father and I sat.

The opposite side of the ground was entirely made up of concrete terraces, packed for rugby Tests but sparsely covered when Test cricket was being played. The MCG, on the other hand, had been reconstructed for the 1956 Olympic Games and was an amphitheatre on a scale I’d never imagined. We had uncovered seats almost at ground level looking down the wicket to the players’ pavilion. The crowd on the second and third days was around 70,000, at least five times the size of any cricket crowd I’d been in. The crush, the heat, and the noise were enthralling. My strongest memory is of the noise. New Zealand cricket crowds were quiet as well as sparse; they had little to shout about.

I sat spellbound on the first morning as Davidson quickly dismissed Peter Richardson, Willie Watson and Tom Graveney, leaving England 7 for 3, and then May and Colin Cowdrey rescued the innings with a century partnership. These players were all familiar to me as names but it was hard to believe I was seeing them in the flesh.

There was no television in New Zealand before the 1960s and the only chance to see Ashes cricket, apart from still photos in the tour books that were a feature of the time, were brief clips on grainy newsreel film at the cinema. Although we were New Zealanders, we supported the home team; my paternal grandfather was an Australian and we’d been brought up to regard doing so as a matter of family loyalty.

I cheered on Davidson as he took six English wickets and was disappointed that my particular hero, the Australian captain Richie Benaud, only managed one. But I also remember May’s elegant off-drives in his innings of 113 (the first century by an English captain in Australia since Archie MacLaren in 1901-02), and his dismissal, bowled (or chucked) out by Meckiff, a ball the bowler later claimed was the best he ever delivered. In my mind’s eye it is quite as fast and unplayable as Johnson’s dismissal of Cook in this winter’s Adelaide Test.

Australia’s innings was dominated by the batting of Neil Harvey and the bowling of Brian Statham. The poised, deft left-hander scored more than half Australia’s total in making 167 and was the only Australian batsman to reach a half-century. Statham’s 7 for 57 off 28 overs on an easy batting wicket, is a rebuke to Anderson’s recent performances. His motto: “If they miss, I hit”, was never better illustrated; Jim Burke, Davidson and Meckiff were clean bowled, Benaud was lbw.

Harvey apart, the batting was attritional and the over rate reprehensible; 18 overs (eight-ball of course) before lunch on the third day produced only 39 runs. It might have been Carberry and Root batting together. May, as usual, was quickly on the defensive and had Trevor Bailey bowling outside leg stump to a leg-side field. By the morning of the fourth day Australia had been dismissed for 308, a first innings lead of just 49. With Australia to bat last, the match seemed evenly poised.

That afternoon England was blown away. The recent collapse in Melbourne came in two dramatic phases, the first after an opening stand of 65, the second after a couple of minor middle-order stands. In 1959 the wickets fell steadily, the flow becoming a deluge: 3 for 1, 14 for 2, 21 for 3, 27 for 4, 44 for 5, 57 for 6, 71 for 7, 75 for 8, 80 for 9, 87 all out. As wickets tumbled, the enormous crowd roared and the decibel level soared. It was as if each successive batsman was being fed to the lions; the amphitheatre had become a colosseum. Nevil Shute’s post-nuclear novel On the Beach was being filmed at a Melbourne beach at this time and it must have seemed to English supporters that that the end of the world had indeed arrived. May top-scored with 17, Davidson completed a fine match with 3 for 41, but the wrecker was the chucker, Meckiff, with 6 for 38.

EW Swanton wrote: “I never saw anything so blatant as Meckiff’s action as, with the swell of the crowd in his ears, he came up that afternoon full pelt from the bottom end towards the pavilion.” I was sitting behind Meckiff’s arm and although thrilled to see England wickets tumbling I remember an uneasy feeling there was something unfair about his action. The English manager, Freddie Brown, had wanted to complain about it after the first Test but May had thought that to do so would seem like sour grapes. There might have been another reason for saying nothing.

Although Australia had several bowlers with suspect actions – the part-time off-spinner Burke, Keith Slater who played in just one Test, and the 6ft 5in fast bowler Gordon Rorke who was brought in for the last two Tests – there were also concerns about Tony Lock’s action, especially his quicker ball. As with the sledging controversy in the recent Ashes Tests, fault was more evenly spread than some English journalists cared to admit.

There’s no doubt that Meckiff and Burke would be suspended today. Shane Shillingford’s action looks innocent by comparison. But, this one day apart, Meckiff’s influence on the series was hardly decisive. The parallel with Mitchell Johnson’s destructiveness is more apparent than real. Even though Meckiff missed the fourth Test through injury, his 17 wickets for the series paled in comparison with Davidson’s 24 and Benaud’s 31 (my disappointment at Benaud’s one wicket in Melbourne was assuaged by seeing him take nine wickets in the next Test at Sydney).

Australia knocked off the 42 runs required to win next morning, with Statham getting another lbw, Colin McDonald for 6. The crowd on this final day was much smaller and when Harvey had fittingly hit the winning run I pushed my way across the ground, pausing to inspect the pitch (such freedoms there were then), and joined the throng outside the team dressing rooms, autograph book at the ready. I must have waited quite a while because I remember Lock, already the worse for wear, coming out from the English dressing room and belching loudly as he passed. Unlike Eden Park in 1956, however, when I’d managed to get the prized autographs of Everton Weekes and a young Garry Sobers, I couldn’t get near enough to the players to add to my collection.

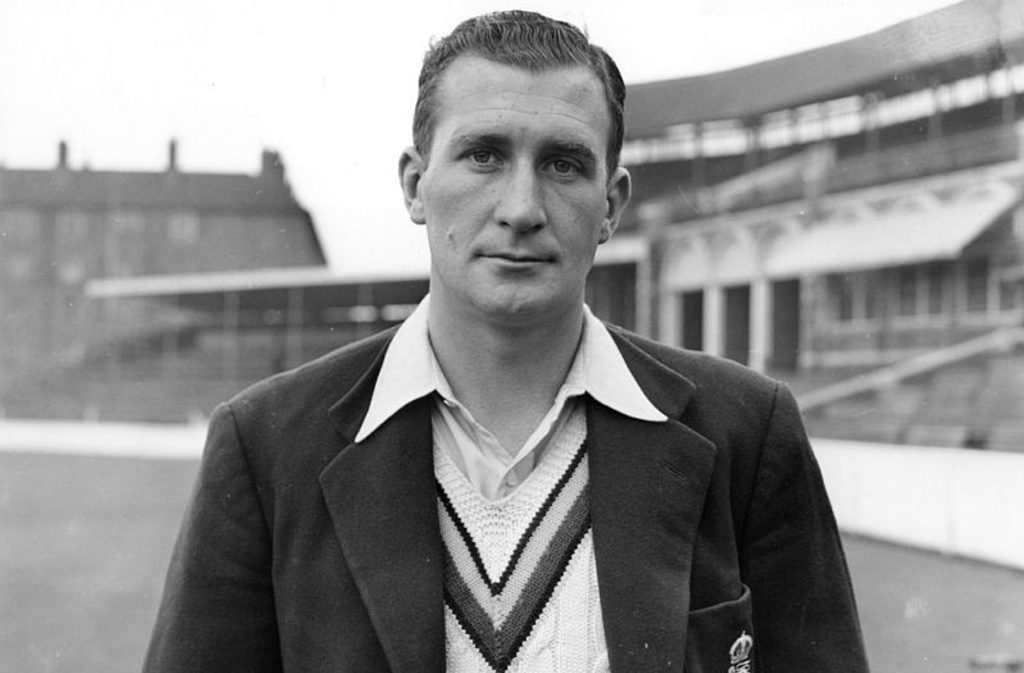

Jim Laker (1922 – 1986) played for both Surrey and England

Jim Laker (1922 – 1986) played for both Surrey and England

Australia went on to win the five-match series 4-0, and a number of the vaunted English line-up never played Test cricket again. Foremost among these was Laker who, in the previous Ashes series in England in 1956, had taken 46 wickets at an average of 9.60, a record that will surely stand for ever. Swann retired mid-way through the current series, but Laker announced his retirement at the start of the tour. Troubled by an arthritic spinning finger that kept him out of the fourth Test, he nevertheless took the most wickets for England in the series, 15 at 21.20.

Lock, on the other hand, fared as disastrously as Swann in the recent tour, taking only five wickets and at a cost of 75.20. Bailey too (four wickets at 64.75, 200 runs at 20.00) was at the end of his career and would never play Test cricket again. Peter Loader and Frank Tyson were others in the vaunted bowling line-up for whom the Ashes series marked the end. And Godfrey Evans, veteran of three previous Ashes tours, still regarded at the start of the tour as the best wicket-keeper in the world, and with several Test centuries to his credit, kept erratically and ended with a batting average of just 4.50.

The resemblances accumulate: for Laker and Lock read Swann and Panesar; for Evans, Prior; for Tyson (three wickets at 64.33), Tremlett and Rankin; for Bailey quite possibly Bresnan. Cowdrey and May both averaged just over 40.00 (a significant difference from the performances of Cook, Pietersen and Bell) but the other established batsmen in 1958-59, Graveney, Richardson and Watson, were disappointing. New Test batsmen such as Arthur Milton (who, like Watson, also played football for England) and Ted Dexter failed. And in a further parallel between the two tours, Evans’ understudy Roy Swetman, brought into the third Test because Evans had broken a finger, batted and kept wicket as unimpressively as Jonny Bairstow at Melbourne and Sydney.

There were also similarities between the out-fielding of both teams. Watching Pietersen and Anderson let the ball run through their legs in the recent Melbourne Test, and Panesar struggling to reach the wicket when throwing from the cover and mid-wicket boundaries, recalled May’s ageing team floundering in the wide open spaces of the MCG. Watson, for example, had an even weaker throw than Panesar’s.

Bobby Simpson dives to dismiss David Allen off Richie Benaud for ten

Bobby Simpson dives to dismiss David Allen off Richie Benaud for ten

His mobility had not been helped by a knee injury, sustained while getting out of a deckchair on the voyage out, which prevented him playing in the early matches of the tour. This geriatric mishap proved to be an augury of the whole tour. No one actually went home early in 1958-9 but Trueman fell out with the manager and was threatened with being sent home. He was later to describe Brown as: “a snob … and a bigot.”

This tale of two Tests, and of two tours, is also a tale of four captains. PBH May (gentleman amateurs still had their initials in front of their surname on the scorecard, professionals after it, thus Trueman, F.) was overwhelmed by the inspirational Benaud. As England collapsed on that afternoon in Melbourne, each wicket was celebrated by the Australian captain running and embracing the bowler and fieldsman (eight of the wickets fell to catches, four of them quite brilliant). Benaud’s Gallic ebullience has long since become standard but he was, I think, the first Test captain to celebrate in such a manner.

Certainly the passion he generated was too much for the trail of incoming and quickly departing English batsmen on that hot afternoon. Benaud’s field placing and bowling changes were imaginative and adventurous. Graveney later spoke of the Australian captain’s “tactical genius”, and of how “he was a master at upsetting the concentration of batsmen and reaching their subconscious.” May, by contrast, captained by rote, his instinct to slow the scoring rate rather than take wickets, his bowling changes predictable, his tactics always behind the play.

For May and Benaud, read Cook and Clarke. Benaud had more obvious charisma than Clarke, but otherwise their styles of captaincy were similar. Both made things happen rather than waiting for them to happen. Both took risks. Both, at the peak of their careers, commanded the respect of their players. May and Cook, on the other hand, became lost and demoralised as defeat followed defeat, retreating into themselves. More than just the defeats were their manner.

A supremely fit-looking Australian team (Norman O’Neill, with a background in baseball, had a throw like a bullet, Harvey, Davidson and Benaud were world-class close fielders) took the initiative and kept it throughout. There were no tight finishes. Everything the Australians tried worked. Even the veteran fast bowler Ray Lindwall, recalled for the fourth Test, took wickets and went past Clarrie Grimmett’s record of 216 Test dismissals.

In both these series England were regarded as too powerful and balanced a combination for the home team. Even a cock-eyed optimist (and one-eyed commentator) like Glenn McGrath was predicting a mere 3-0 result for the home team (he did, however, also predict that Mitchell Johnson would be the man of the series). The statistics of both series are remarkably similar. In 1958-59 three Australian batsmen – McDonald (64.87), O’Neill (56.40), Harvey (48.50) – headed the batting averages for the series. May and Cowdrey were next, but after that the averages fell steeply away to Graveney (31.11), Richardson (20.25), Bailey (20.00) and Watson (18.00).

England’s bowling statistics were dire, the leading wicket-takers being Laker (15), Statham (12), Trueman (9) and Loader (7). Broad apart, England’s bowling in the recent series was also poor. Although batting collapses have been the main story, the bowlers’ inability to dismiss Australia’s lower order was equally the reason for the “whitewash” (McGrath’s description of this “whitewash” as the “icing on the cake” deserves a Colemanballs “journalist of the series” award). Anderson, with 14 wickets at 43.92, and 30 more overs than anyone else, has been treated much more kindly than Pietersen and Carberry.

Both these England teams were thought to be as strong as any to have left the country for many years, but finished the tour in disarray and facing the problem of rebuilding. Both these Australian teams, led by aggressive, imaginative captains, with a more relaxed and supple management behind them, and supported by enormous crowds with rediscovered belief in their own side, produced results that in prospect seemed most unlikely but in retrospect inevitable.