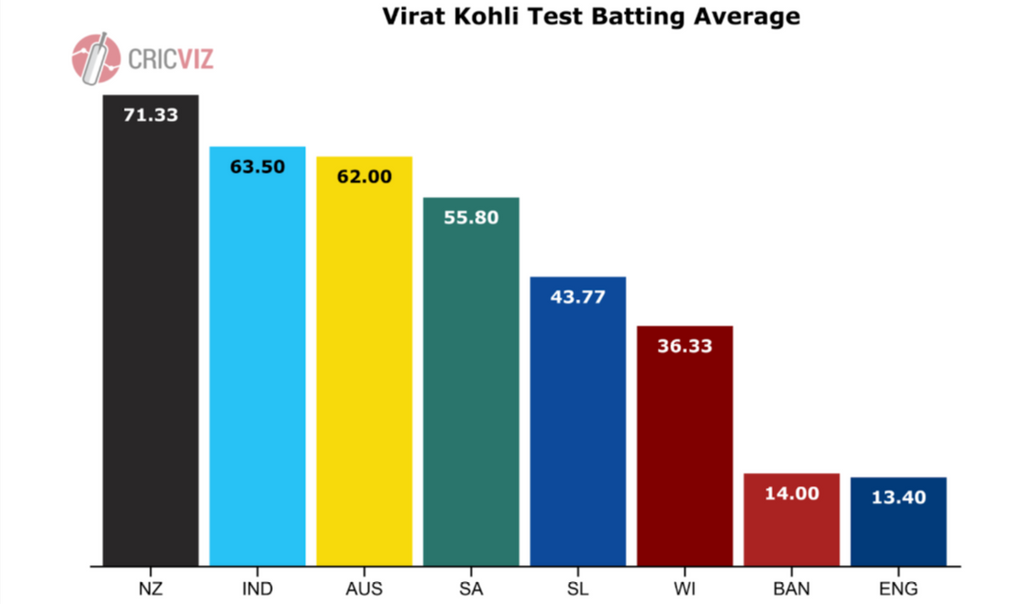

Virat Kohli returns to England a far greater player than the man who averaged 13.40 in 2014. CricViz analyst Ben Jones picks apart the constantly shifting batsmanship of the Indian captain.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz, the cricket intelligence specialists

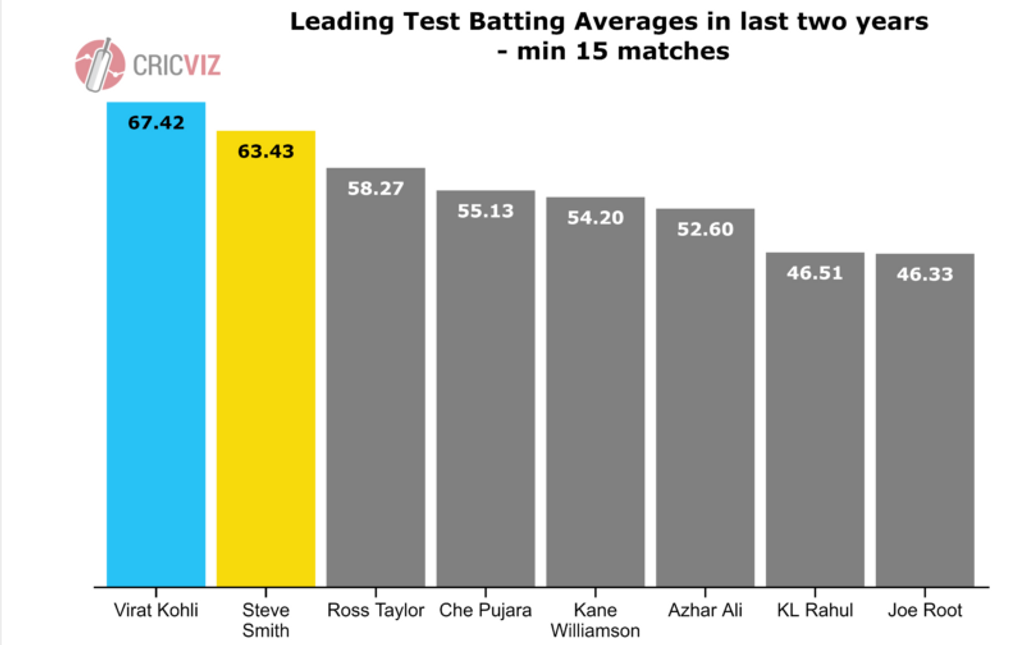

Given the identity of the two captains, it’s likely that the Test series between England and India will in part be viewed through the lens of “The Big Four”. Root and Kohli, alongside Steve Smith and Kane Williamson, have for some time been considered the best four batsmen in the world. It’s a neat term, which works across all formats, but in Tests it really is more of a “Big Two”. When it comes to the longest form of the game, Smith and Kohli are a cut above.

These two Test giants have very different technical approaches. Smith is the classic autodidact, his twitchy stance and hovering back-lift unlikely to be found in any batting manuals, but his triumph has been based on complete trust in this method – trust which it’s fair to say has been vindicated, after 6,199 Test runs. By contrast, Kohli has always worked from a broadly classical standpoint, with a few personal flourishes thrown in, but arguably his greatest asset has been his willingness to change his technique across his career, to refine his strengths and eliminate his weaknesses.

The earliest and most profound example of this can be found in his response to the catastrophic tour of England in 2014. Many are suggesting he could struggle this coming series because of the issues he had in that 2014 series. In part, this is reasonable criticism – nowhere else in the world does he average less than he does in England.

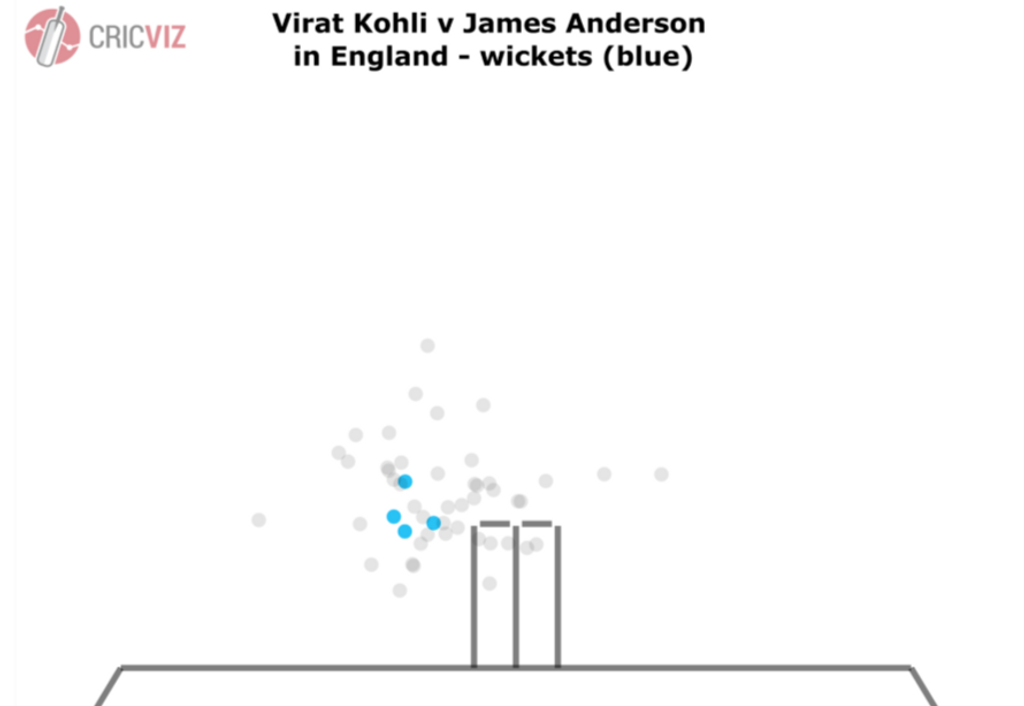

However, the narrative that’s taken hold of Kohli becoming a walking wicket as soon as he lands at Heathrow, as with all sweeping judgements of this type, is a reductive one. The Indian captain didn’t struggle simply with English conditions, he struggled against arguably the greatest exponent of those conditions cricket has ever seen. Kohli faced just 50 deliveries from James Anderson in England; he was dismissed on four occasions.

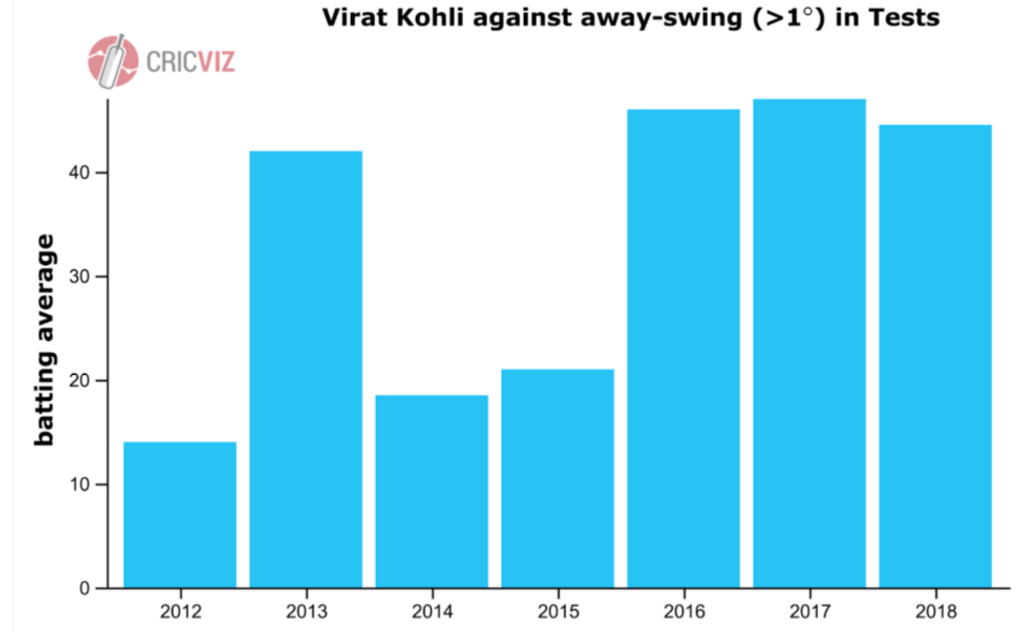

This poor head-to-head record comes from the Englishman’s skill in swinging the ball. At that point in his career this was Kohli’s real weakness. From the start of his Test career, to the end of that 2014 tour of England, Kohli averaged just 14.33 against deliveries swinging more than 1° away from him. When you consider that 43% of Anderson’s deliveries swing that much, and 38% of his deliveries to right-handers are out-swingers, Kohli’s struggles were completely understandable. 2014-era James Anderson was a bowler almost lab-produced to dismiss 2014-era Virat Kohli.

Regardless of the disproportionate nature of the criticism this attracted, that tour was the first bump in Kohli’s rise, and sparked a barren two years for him against the swinging ball. In 2014 and 2015 he averaged just 18.50 and 21.00 against away swing, the exposure of such an obvious technical issue prompting questions about Kohli’s potential for the first time in his Test career. In increasing numbers, people were wondering whether Kohli would focus on white-ball cricket, hiding from the moving ball.

Seeking out Sachin

The criticism clearly stung. Yet in a situation where sportspeople often retreat into themselves, return to what they are good at and refuse to adapt, Kohli showed considerable humility and sought out help – albeit from a source where deference is to be expected:

“Sachin helped as he told me that I have to approach a fast bowler (forward press) just like you approach a spinner. One has to get on top of the ball not worry about pace or swing, you got to get towards the ball and give the ball lesser chance to move around and trouble you.”

In terms of “getting towards the ball”, Kohli clearly took this on board, and made a pronounced change to his technique. In 2014, his average contact point with the ball against seamers was 1.87m away from this stumps. In 2015, with Tendulkar’s advice still fresh in his mind, it was 2.2m, a clear indication that he was getting further forward, batting further down the track. For an elite Test batsman, batting 33cm further out of your crease is akin to adding another wheel to a Formula 1 car.

As well as willingness to take advice, Kohli showed his own understanding of the issue that was affecting his batting.

“The problem with me was that I was expecting inswingers too much and opened up my hip a lot more than I should have done. I was constantly looking for the inswinger and was in no position to counter the outswing…I used to stand at two leg (middle stump) and my stance was pretty closed and then I figured out that after initial movement of the back foot, my toe wasn’t going towards point rather it was towards cover point, so my hip was opening up initially. So to get the feel of the ball, I had to open up my hip as I was too side on. Anyway, I had too much of a bottom hand grip and I didn’t have too much room for my shoulder to adjust to the line of the ball, so it was getting too late when it swung in front of my eyes.”

[breakout]I was constantly looking for the inswinger and was in no position to counter the outswing[/breakout]

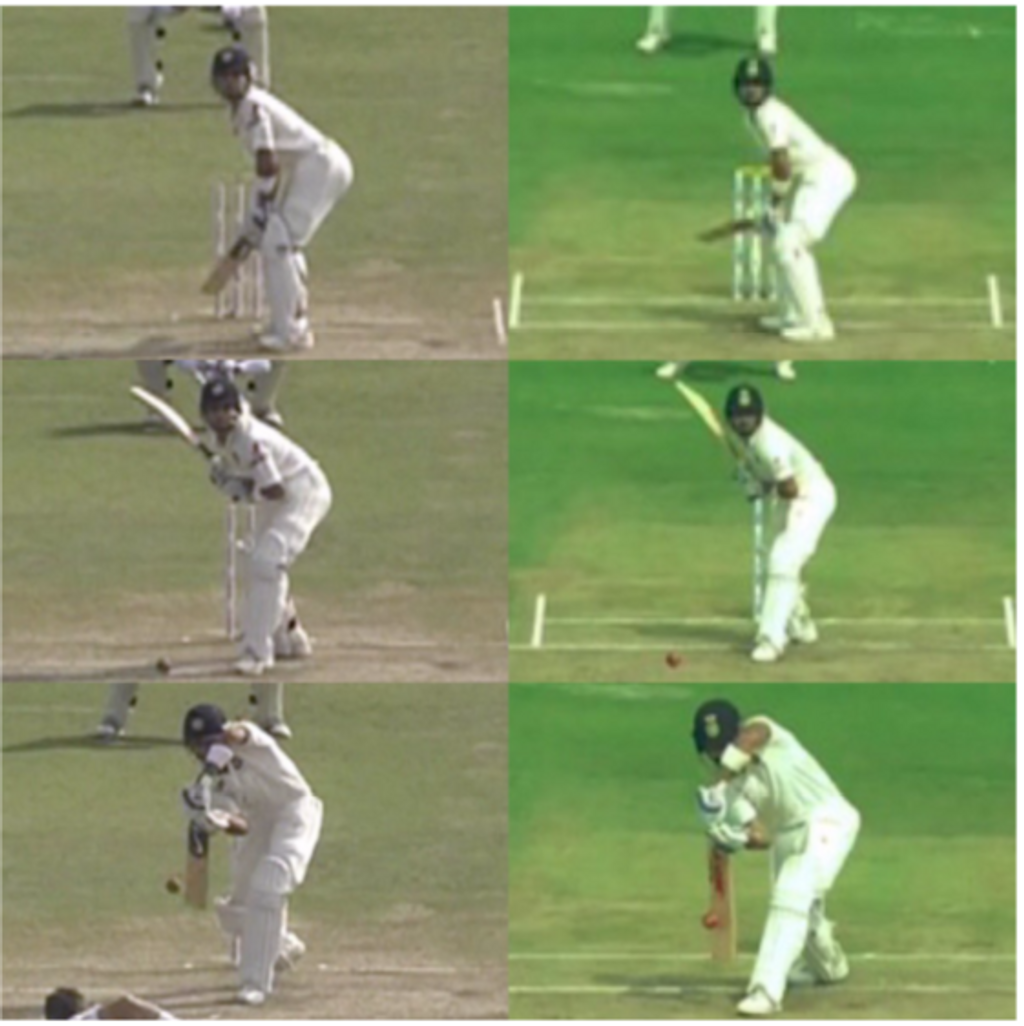

Nobody who has watched Kohli’s transformation as a player since that England series could fail to be impressed by the man’s cricketing self-awareness. Pinpointing down to a minute detail the technical fault causing his issue against swing, he closed his stance off, bringing the top-hand far more into play. The images below are from England’s tours of India in 2012 and 2016, Kohli facing Anderson – the difference in stance is clear. His forward press is significantly greater, and it starts earlier, meaning that his bat comes down perfectly vertically to defend the ball. The more closed off stance makes this easier, as it naturally brings the top hand into a more dominant position.

In due course, these technical changes bore fruit, in the form of heaps and heaps of runs. Kohli, replete with the new, more closed stance, averaged over 70 in Tests in both 2016 and 2017. However, the most important change came in his record against the moving ball. Since that litany of technical changes in 2015, he’s averaged over 40 against away-swing in every calendar year.

Wide line of attack

However, the elimination of one weakness created another, albeit one which wouldn’t be exposed until the next time Kohli faced up against Alastair Cook’s men. In the 2016 tour of India, England’s bowlers had very little success across the board, but did at least manage to establish a pattern of play against Kohli. Three times their seamers dismissed Kohli with deliveries very wide outside the off stump, a typically defensive line of attack. It was a series which Kohli dominated, averaging 109.16, but once more whispers were to be heard that here was Kohli’s weakness, here was the chink in the armour.

It was a good spot; Kohli had developed a weakness to that wide line. Perhaps by setting up further down the track to negate swing, Kohli’s ability to judge the line of the ball was affected, his desire to get on top of the seamers leading him to attack balls he shouldn’t.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”0″][/breakout]

Regardless, it affected his game. In 2013, he’d averaged 67 against that wide line, but from 2014 until 2017 he averaged 28.18. Other bowling attacks followed England’s lead; before that 2016 tour, 20.8% of deliveries to Kohli were wide outside off, but since then it’s leapt to 26%.

To this strategy, Kohli adapted quickly. To the naked eye, he seemed to close off ever so slightly more, and focused more on scoring through the area he was being invited to hit into. Previously, he’d scored just 45% of his runs against pace on the off-side; since this tactic came into vogue, that’s leapt to 56%. As this graphic illustrating Kohli’s scoring zones in Tests against pace shows, he went from scoring 28% of his runs through point in 2013, to 47% in 2018.

By changing his stance to cope with this wider line, he exploited the extra width to score more heavily through point, and more quickly. Before 2017, Kohli scored at 3.29rpo against those wide deliveries, but since then he’s scored at 4.46rpo. Crucially, as bowlers targeted this weakness more and more, Kohli’s record improved; since the start of 2017 he has averaged 103.00 against those wide deliveries.

Target the stumps

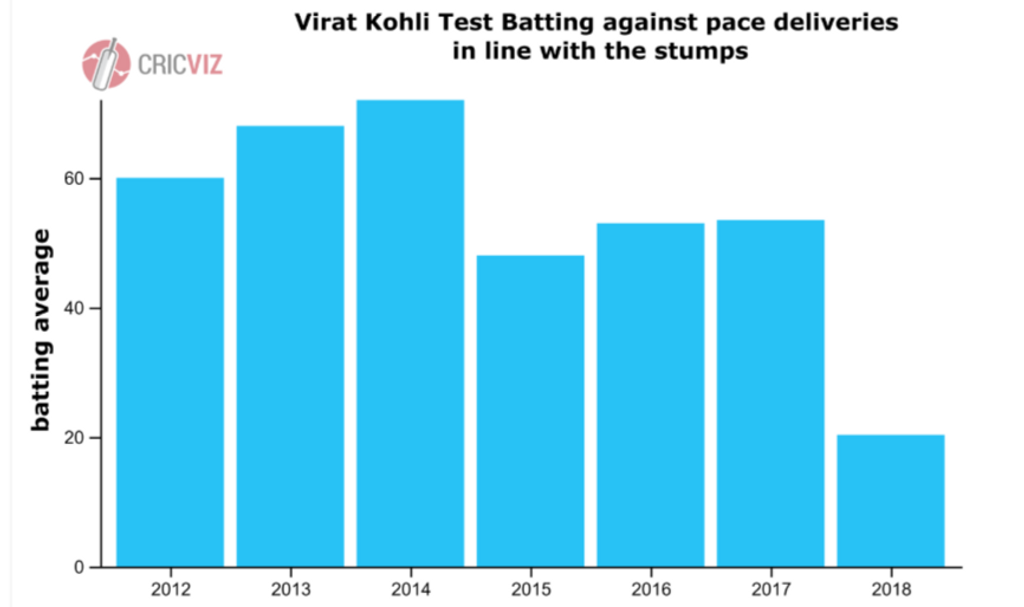

Another year of relentless run-scoring followed, but the next shift in tactics for how to bowl to Kohli would once again come in a high-profile series. As Kohli’s stance became further closed in order to improve outside the off stump, he’s begun to struggle against straighter bowling. From 2015 onwards, the moment when he first started to close off that stance, tighter lines have started to cramp him – a total transformation from the man who was “constantly looking for the inswinger”.

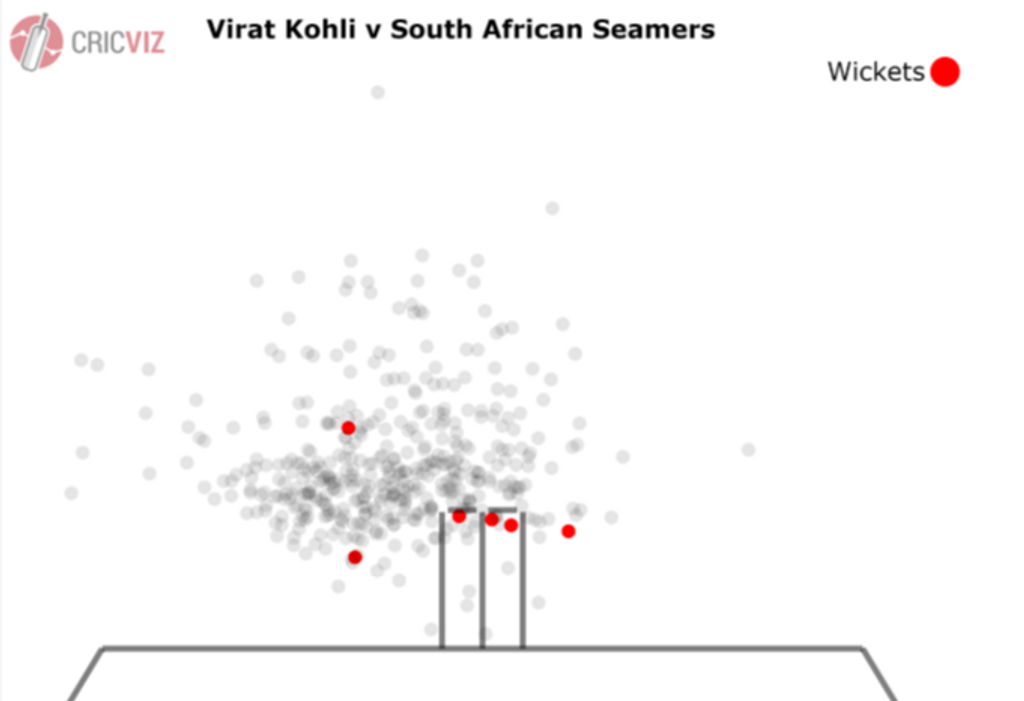

Perhaps frightened of Kohli 1.0, the batsman who would whip everything straight through midwicket, bowlers hadn’t really cottoned on to this line of attack. The strategy came to the fore most obviously when India toured South Africa earlier this year. In a series where Kohli had qualified success, averaging 47.66, he struggled hugely against deliveries on his stumps.

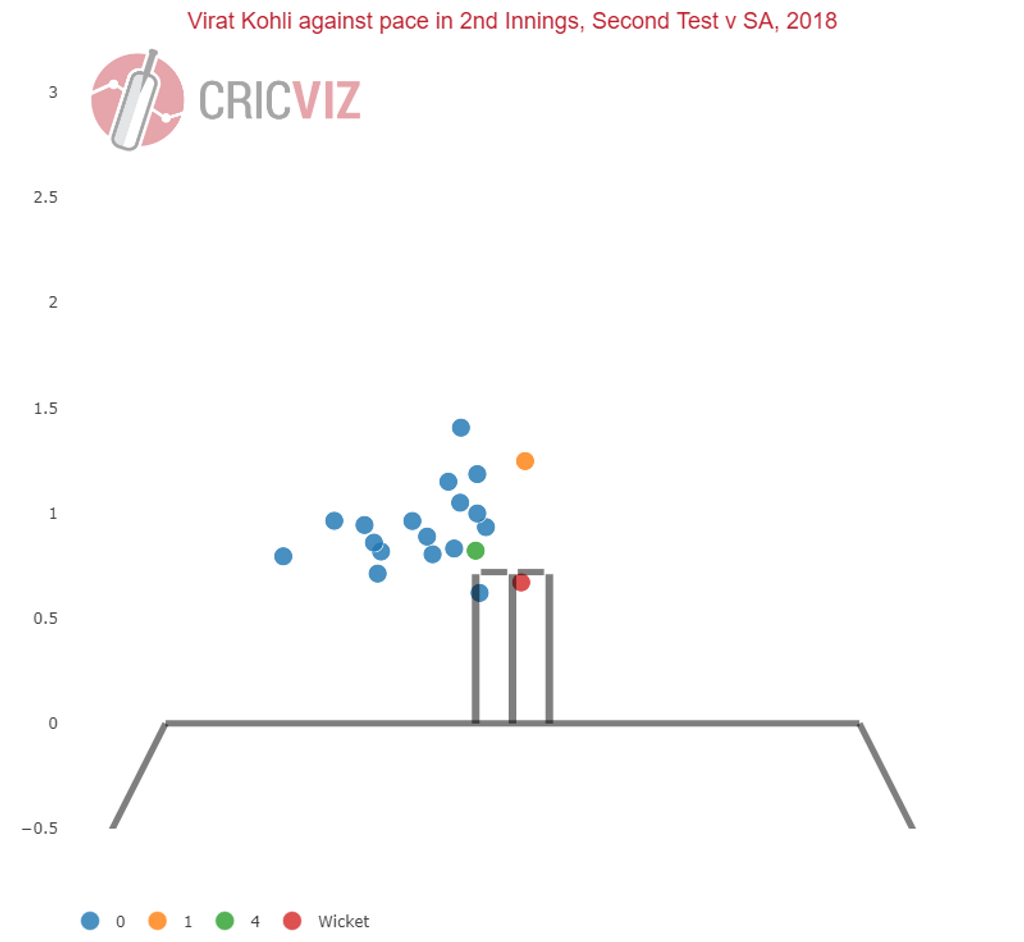

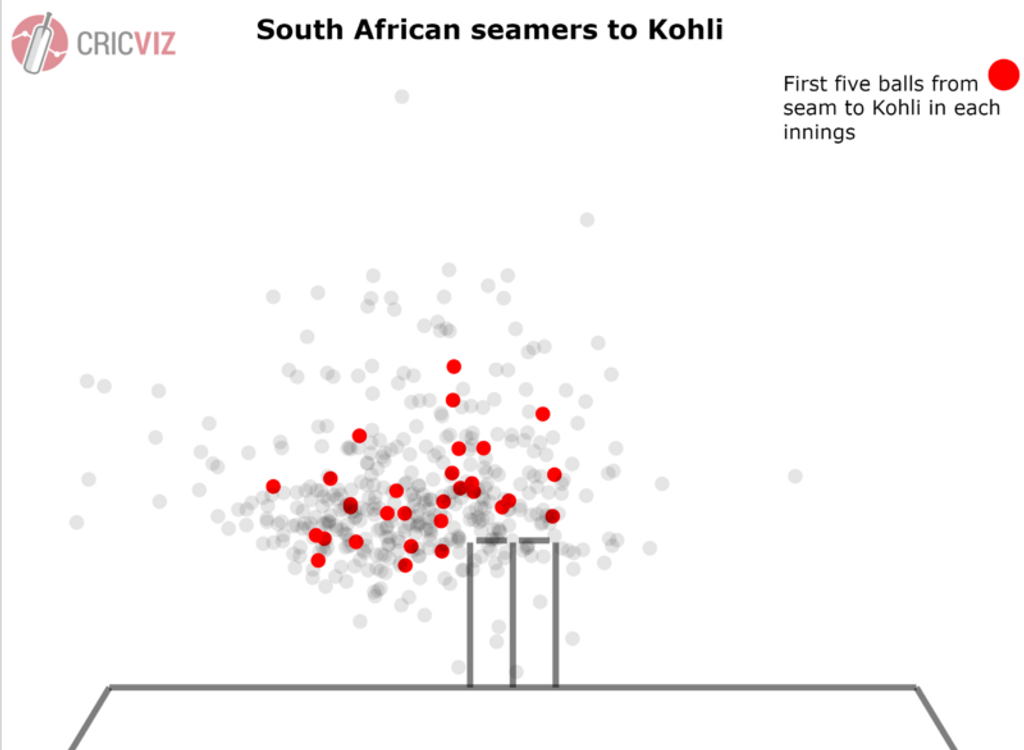

Faf du Plessis’ team had a preferred pattern of play to Kohli, best exemplified in their approach in the second innings at Centurion. Early on in the innings, Rabada et al would hang the ball outside the off-stump, trying to lure the Indian captain into the old trap. Then, as the surprise ball, they’d dart one back into his pads. Across the series, Kohli faced 17 deliveries on the stumps from seamers. He was dismissed three times.

The key to this tactic is patience. In each of Kohli’s six innings on tour, not one of the first five deliveries South Africa’s seamers bowled would have hit the stumps. Arguably, the tactic worked because it was such a subtle tweak to the “sixth stump” strategy, which Kohli had come to dominate.

England need patience

England’s hopes this summer could rest on this tactic. If they can establish a similar pattern of play to South Africa, then they might be able to limit Kohli. Their attack may not be able to replicate it – in the Centurion example, the wicket ball was 140kph from Rabada, and England have no bowler capable of hitting those speeds regularly – but it’s the strategy which has most recently had success against Kohli. It’s worth attempting.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”1″][/breakout]

Because the hope for bowling attacks all over the world is that however successful these technical overhauls are in the long run, they do leave Kohli briefly exposed. Like a blanket that’s too small, so that pulling it up to cover the body leaves the feet exposed, radically shifting your technique to counteract a weakness can’t help but create another weakness elsewhere. For a while after Kohli has changed his stance, there is always a window of opportunity, where a weakness lurks in his set-up, unknown and unidentified, but there.

In summary, England should resist trying to find a silver bullet for Kohli. Bowling wide may work, but it might not. Getting the ball swinging away from him might work, but recent form suggests not. Bowling the odd ball on his stumps is worth a try. But most importantly, they should be flexible, because a man like Kohli who’s just had a terrible series against full, straight bowling at the stumps, is unlikely to come out and bat the same way. If England can stay flexible and attentive, there should be a crack to exploit. They just have to find it before Kohli does.