What England are actually doing differently in one-day cricket these days.

Eoin Morgan’s England team have come a long way since the last time they were in Australia. From the most underwhelming World Cup performance in recent memory, crashing out in the group stages from a format tailor-made to help them progress, they have returned to batter the champions of that tournament 4-1 in their own back yard. But how did they do it? Ben Jones has used CricViz data to analyse the five reasons why Morgan’s white-ball team have gone from World Cup chumps to potential champs in less than three years.

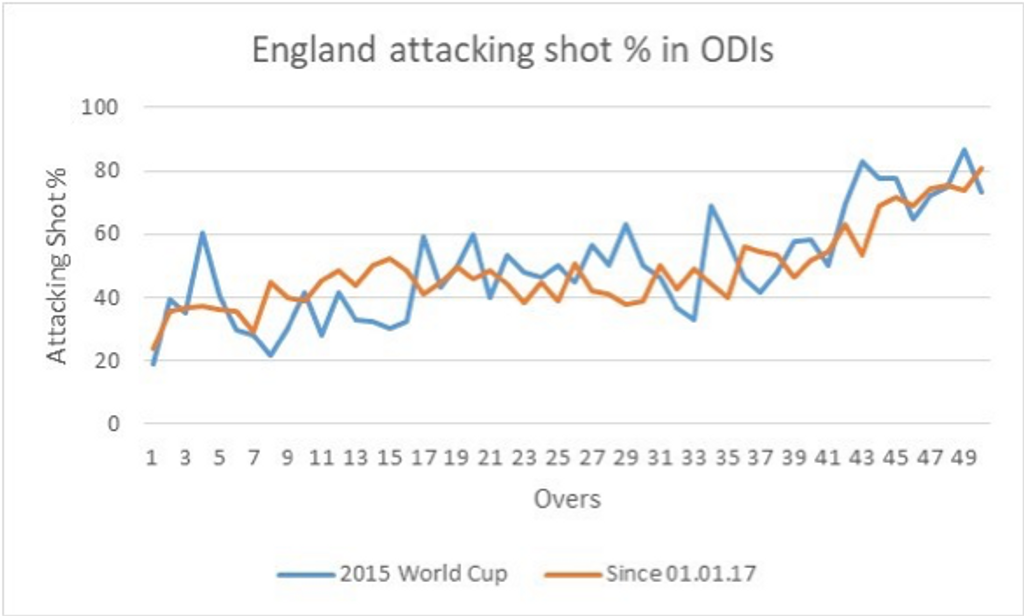

Attacking execution, not intent

Remarkable though it may seem, England’s batsmen played 46.5% attacking strokes at the World Cup, and only 46.2% in this ODI series. On top of this, whilst the scoring rate when they attacked at the WC was 8.16rpo, in this series it was only 8.56rpo, just a 5% increase. For all the talk, England’s white-ball revolution has not come purely because of a change in mind-set. So why are England regarded as so much more aggressive now, given they’re playing marginally fewer attacking shots than they have before?

The difference has come in the execution. When attacking at the World Cup, England missed or edged the ball 20.3% of the time, with a batting average of 28.03. In this victorious ODI series, England only edged or missed 15.7% of the time when attacking Australia’s bowlers, and averaged a far healthier 37.68 when doing so. Morgan and Bayliss haven’t just told their batsmen to attack more – they’ve selected batsmen capable of doing so.

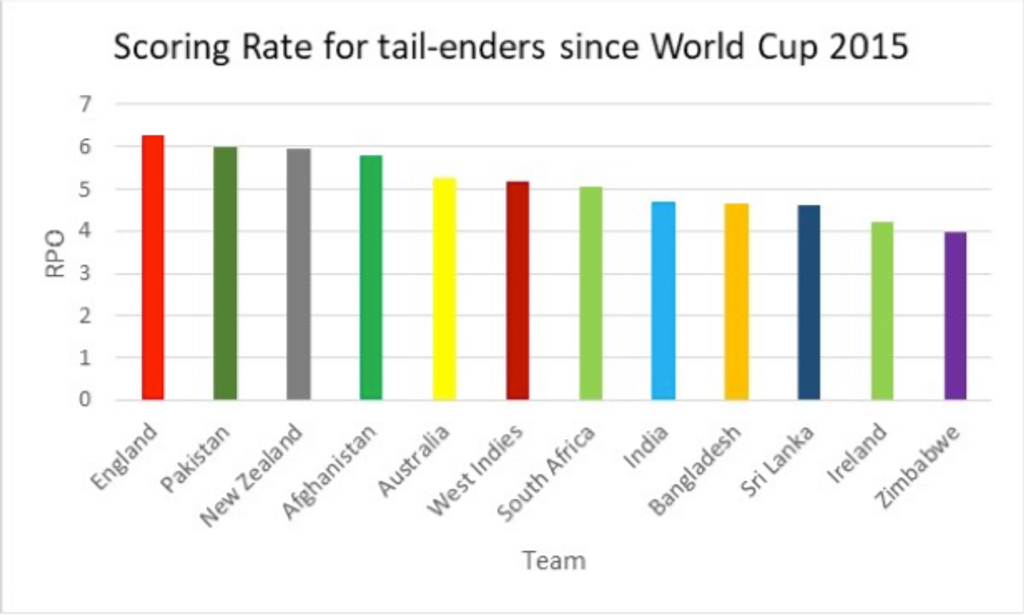

Late-order batting

There is undoubtedly a resilience to England’s tail-order these days, and it is combined with a fierce ability to counter-attack. At the World Cup, England’s last five batsmen averaged 23, scoring at 7.91rpo – in the 4-1 victory over Australia this soared to an average of 39 and a scoring rate of 9.81rpo. In this case, much of that uplift was down to the performance of all-rounder Chris Woakes, but it is easily forgotten that he played four of England’s six matches at the World Cup, and scored at just 6.98rpo. His improvement is in many ways emblematic of the improvement of the unit as a whole, and the newly discovered late resistance is winning England matches. Australia’s Nos.8-11 contributed just 84 runs this series; England’s contributed 245.

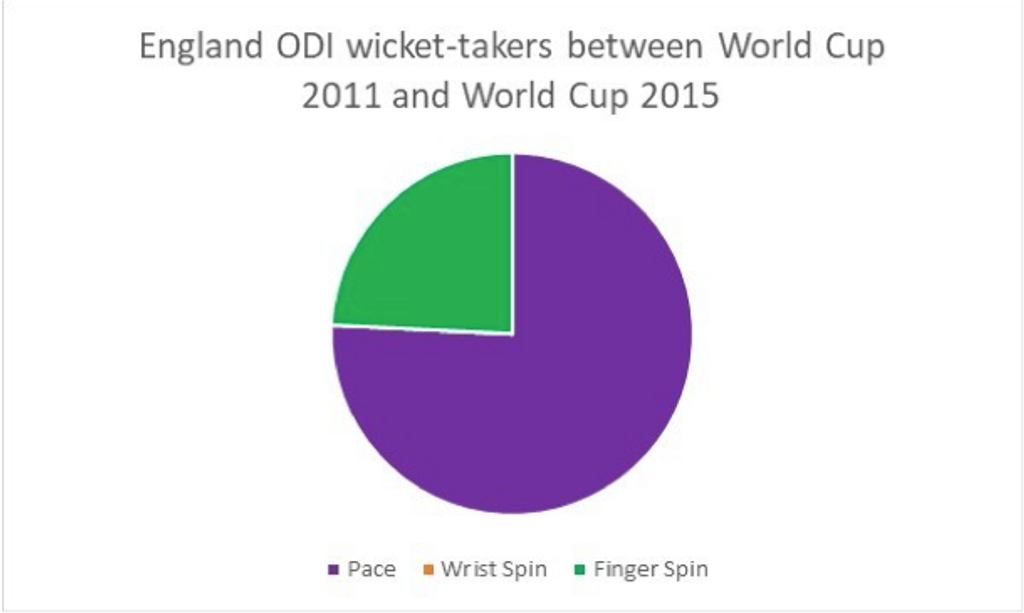

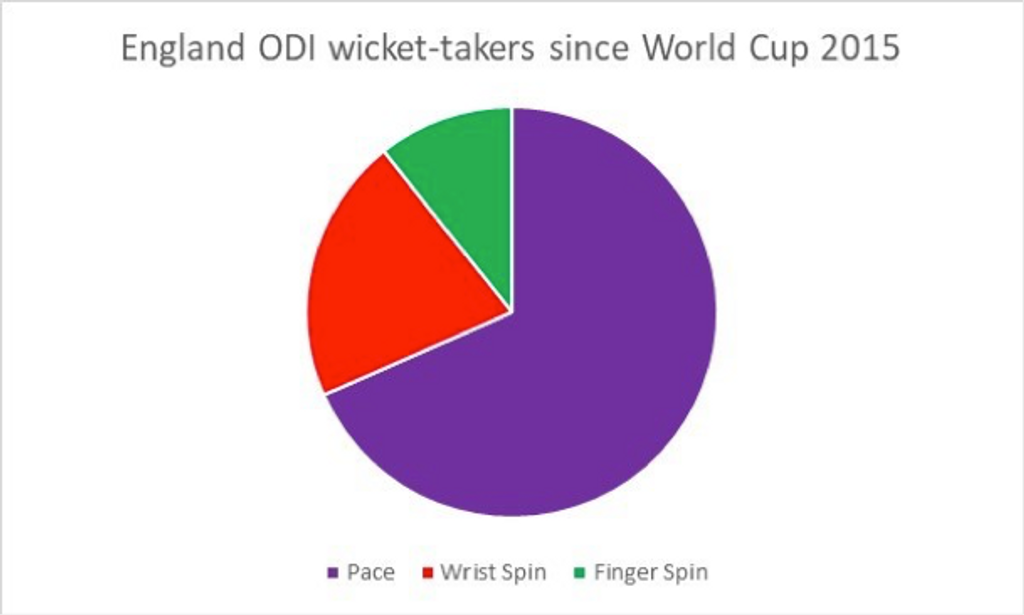

Quality spin bowling

It is a mark of how far England have come that when Adil Rashid was dropped for the opening match of the 2017 Champions Trophy in July, most onlookers were bemused. England’s attitude towards wrist-spin, both that of the staff and fans, had moved swiftly from scepticism to love. Rashid is the leading ODI wicket-taker since the last World Cup, and has been both a pivotal figure in the revival of the white-ball team, and a sign of a more inventive, experimental approach.

That approach has paid dividends. Wrist-spin is typically a more high-risk option, but one which brings more reward, and this has been borne out. At the World Cup, England’s spinners had an economy of 5.22rpo, and took a wicket every 54 deliveries – this series, the economy has lifted to 5.51rpo, but they now take a wicket every 39 deliveries. England’s spinners drew 64 false shots across 5 games on this tour, compared to just 26 at the World Cup. The caveat that they bowled 670 deliveries of spin in this series, compared to just 324 then, does apply. However, the 106% increase in spin deliveries does not account for the 140% increase in false shots – and disregards the idea that this increased trust in spin may in fact be contributing to their improved performance.

Genuine pace

On top of this success for the spinners, England have found something with the white-ball they’ve lacked in the Test arena – raw pace. Across their six matches at the 2015 World Cup, England’s seam bowlers sent down 188 deliveries over 140kph.In their five matches on this tour, they bowled 277. That’s a 47% increase, an increase which is even more remarkable when you consider that by the final match of this tour Bayliss had been forced to field an entirely second string seam bowling unit.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”0″][/breakout]

Flexibility

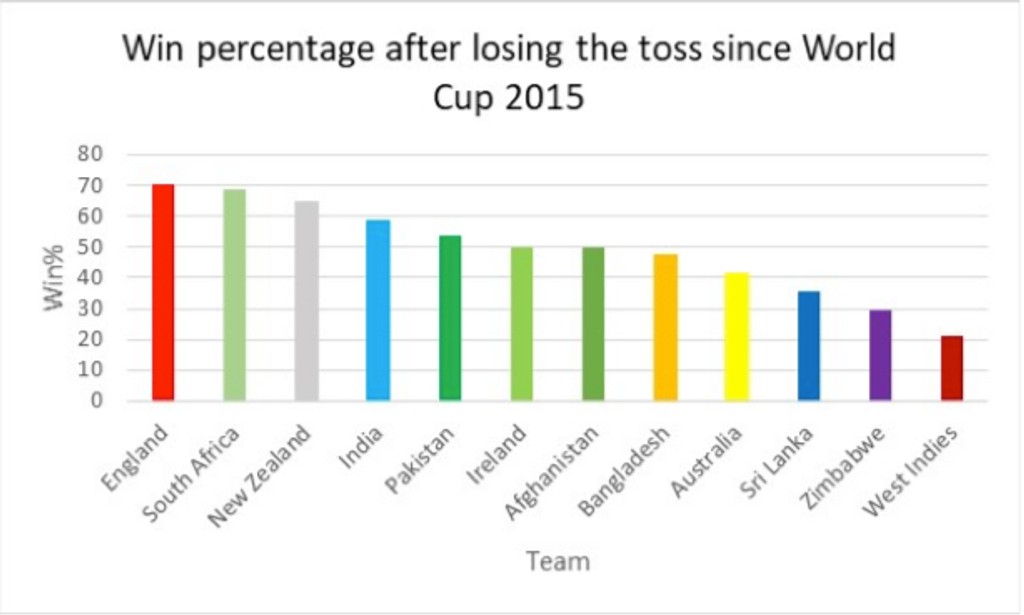

Aside from the technical issues we’ve outlined, there is a new strategic flexibility to England’s ODI team, which is allowing them to win matches in different circumstances. Between the last two World Cups, in 2011 and 2015, England won 49% of games they played. Coincidentally, they also won 49% of matches when they lost the toss.

However, since the dismal World Cup campaign in 2015, England win 66% of matches they play, a significant upswing which can be partly attributed to them now winning 71% of matches when they lose the toss. That is the largest winning percentage for toss-losing teams in the world, since the last World Cup, and this adaptability is key.