Cricviz’s Ben Jones argues that Ben Stokes should be England’s No.1 Test No.3.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz.

Conventional wisdom is messing with England’s batting order. It forced Joe Root up to number three, because ‘that’s where the best batsman bats’, despite it being a position he neither suits nor wants. It’s forced them to bat their wicket-keeper without the gloves lower than their wicket-keeper with the gloves, because a player like Jos Buttler surely couldn’t bat in the top five for a Test side. It’s forced them into picking Ollie Pope, a young man who had never batted higher than six for his county, at number four in a Test match against the best side in the world.

The issue with applying conventional wisdom to this side is that England don’t have a conventional group of cricketers. As many writers and pundits have noted, England are blessed (or cursed) with a pool of players who all seem ideally suited to batting at No.6 or No.7. Moeen Ali, Ben Stokes, Jonny Bairstow, Chris Woakes, Jos Buttler, Sam Curran – all wonderfully gifted cricketers, who all naturally occupy the same spot in the side.

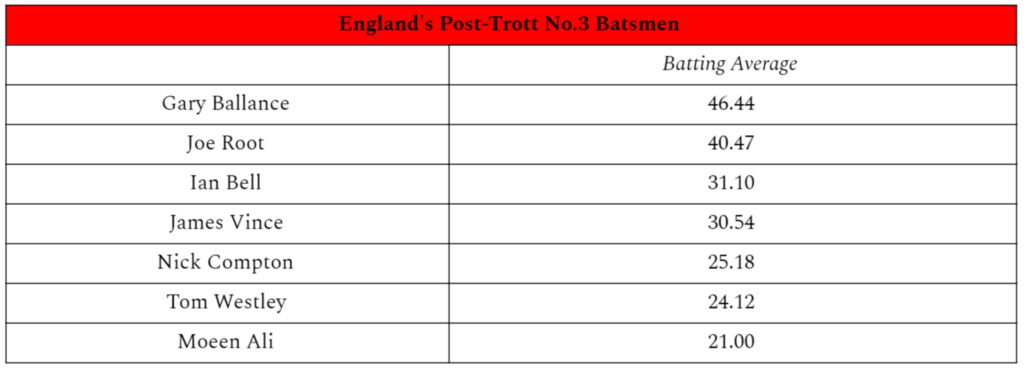

This wouldn’t be an issue if the top order was functioning properly, but it isn’t. Much has been made of England’s failure to replace Andrew Strauss, but the attempt to replace Jonathan Trott has been just as arduous. England have tried seven different players at three since Trott left the touring squad in 13/14; only two (Root and Gary Ballance) have averaged over 35 in the position. They are a Gary Sobers of a side – in that they have six sixes, keep up – but they don’t have a single number three. It’s all a bit of a mess.

The selectors have shown a willingness to kill two birds with one stone with this issue. Promoting Moeen Ali to three at The Oval had the dual benefits of spreading the batting talent more evenly across the line-up, allowing Root to bat at his preferred number four spot (where he averages 52.90 compared to 40.47 at three), and giving a talented batsman room to reach his full potential. As a strategy, it makes complete sense.

So why not promote Ben Stokes to three?

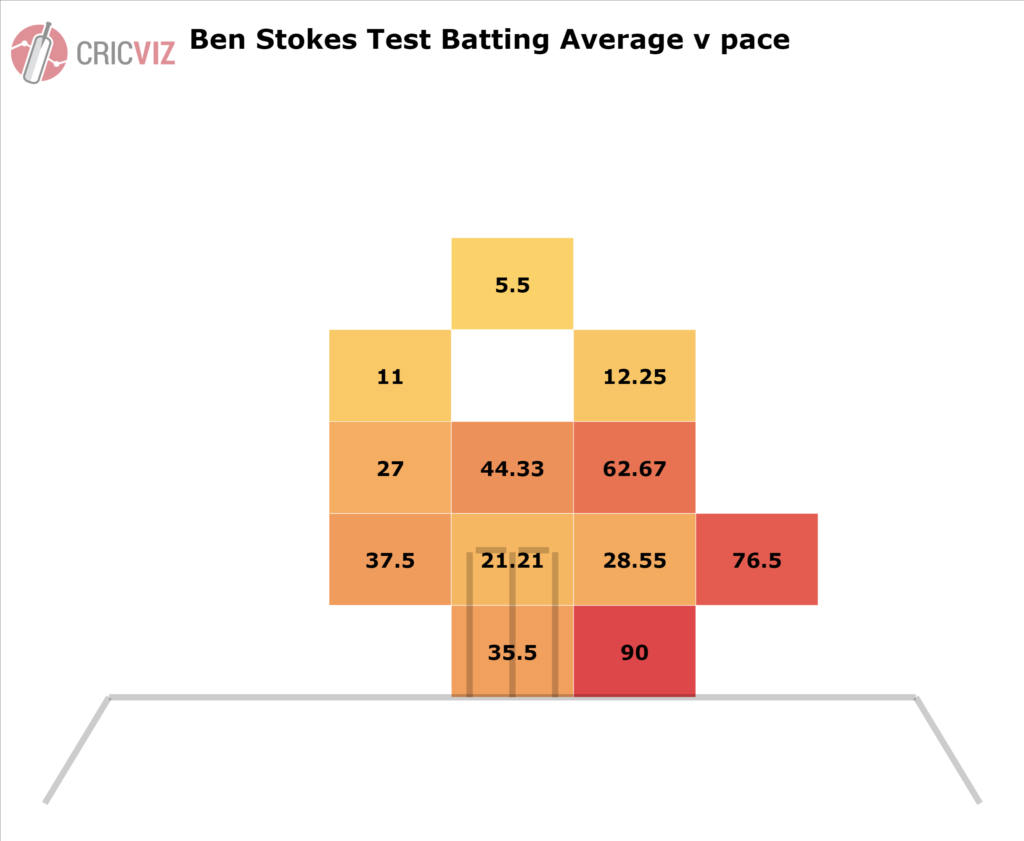

After all, Stokes has the best technique of any English batsman. His attacking shots are crisp, his defensive strokes thrown down emphatically like he’s flourishing a royal flush. His alignments are precise, his trigger movements clear and unerring. Look past the cliché of the tattooed slogger, the reputation of a white-ball gun, and what you’ve got is a superbly technical batsman, with no weaknesses other than those that plague all batsmen.

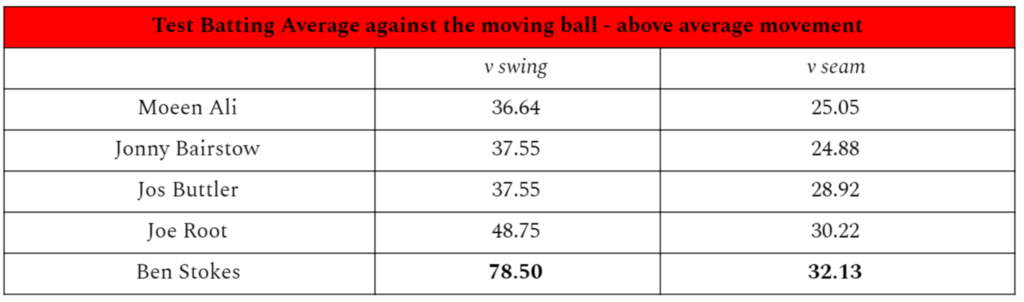

There is plenty of evidence which suggests that of this group of players, Stokes is the best equipped to cope with the challenges of top-order batting. The data implies that among England’s middle order who ended the Test summer, Stokes plays the moving ball better than any. Against deliveries moving more than the global historic average, Stokes averages the most against both swing and seam bowling.

This will come as a shock to some. Stokes’ role in the Test side has rarely been about negotiating the moving ball; it’s been about counter-attack, coming in late in the innings and exploding off a pre-built platform.

Yet Stokes doesn’t actually perform best in that kind of situation. When he arrives at the crease in the 60th over or later, he averages 26.71. By contrast, when he arrives at the crease in the first 20 overs of a Test innings (something he’s done on 22 occasions), he averages 35.68. Putting aside the vagaries of batting position, when Stokes comes out to bat against a newer ball, with all the challenges that brings, he performs better than when he arrives later in the innings.

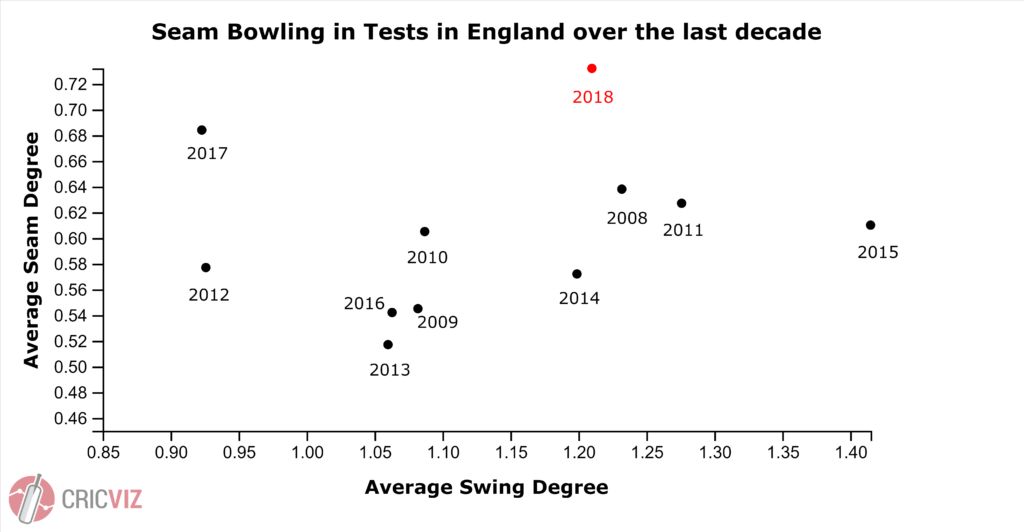

The time also feels right to demand more from Stokes with the bat. This summer has been a difficult one for him personally, but as a batsman he has seemed to significantly mature. In an English season which has seen more seam movement than any other in the past ten years, Stokes adapted his approach, playing more within himself than we’ve seen before in Test cricket.

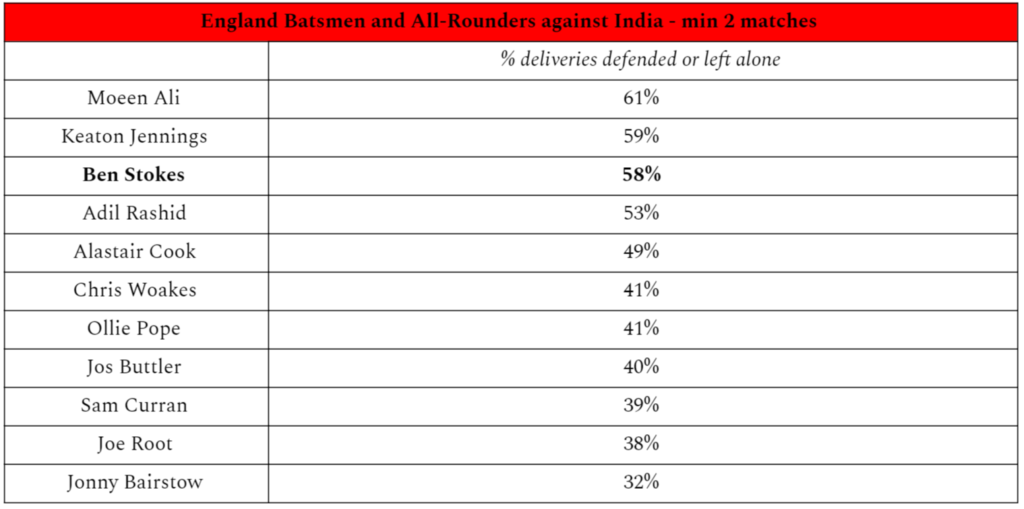

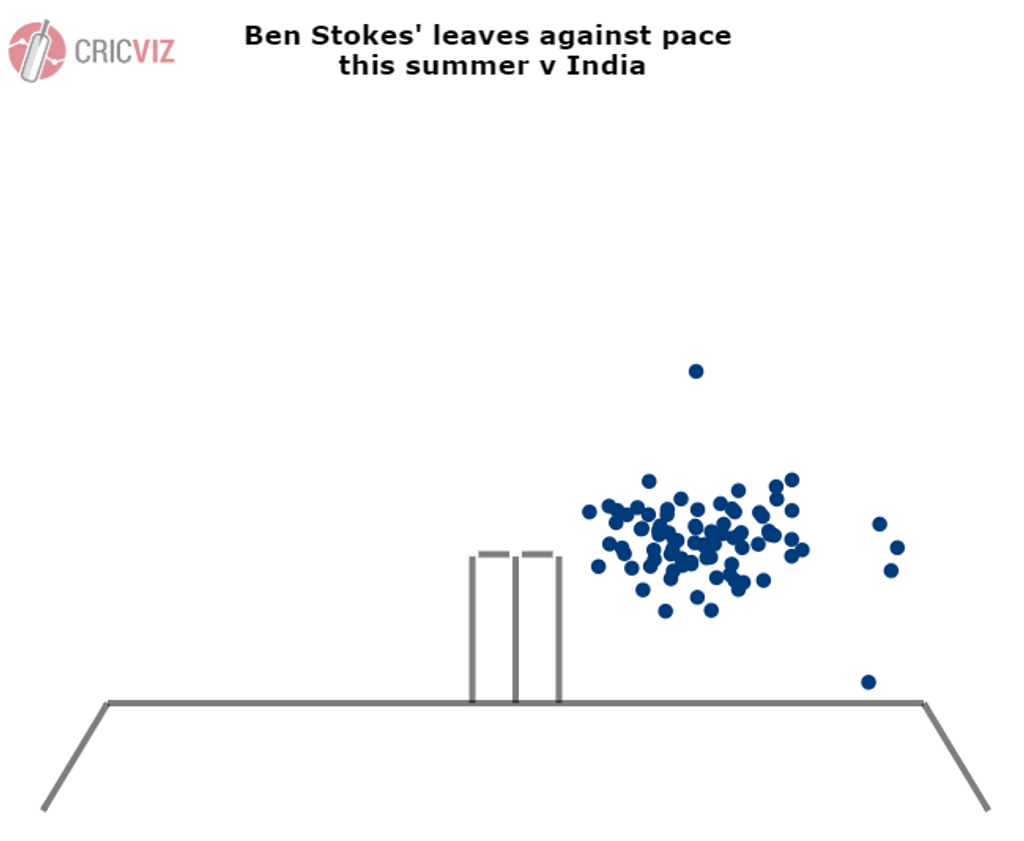

In the series against India, he left or defended 57.9% of his deliveries, his highest figure for any Test series where he’s played three or more times. Across the series, Stokes left 94 deliveries, the most he’s left alone since his debut series in Australia five years ago.

Whilst this more cautious method does not guarantee success – as shown by Keaton Jennings’ presence near the top of that list – for both Moeen Ali and Stokes himself it illustrates an ability to bat at a different tempo when the situation requires them to do so.

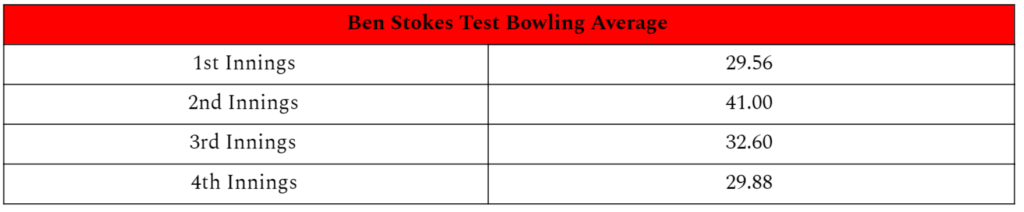

Conventional wisdom would suggest that promoting Stokes would affect his bowling, due to the likely increase in batting workload. However, there is evidence to suggest that Stokes’ current workload already takes a substantial toll on his effectiveness. His bowling average in the first innings of a Test match is 29.56, which rises to 41.00 in the second innings. When he’s already batted, regardless how long for, his bowling suffers.

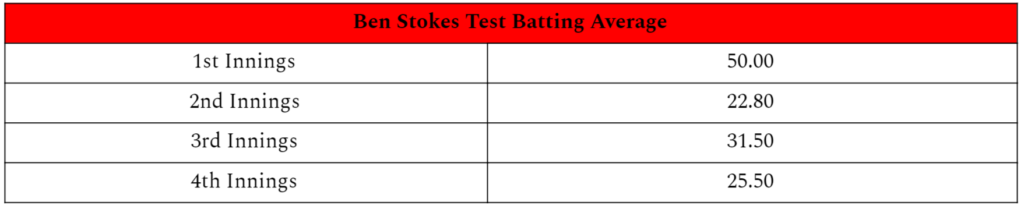

The same story is true when we look at Stokes’ batting returns. When he hasn’t already been in the field, his batting average is elite. When he has, his batting average is 26.82.

This isn’t a desirable pattern, and one that needs to be addressed. Arguably, England need to make a choice between Stokes becoming more batting focused, or more bowling focused. He clearly has more ability in either area than he is able to show at the moment, because of the demands on his body and mind from being pulled in all directions.

England don’t have enough top-class batsman to be limiting Stokes’ productivity with the bat in this way. When England’s lower order contains all of Woakes, Curran, Moeen, and Rashid, picking a batsman of Ben Stokes’ class and having him bowl substantial numbers of overs is, bizarrely, the conservative choice. Put simply, England need Stokes’ batting more than they need his bowling. That might be a tough sell to a man who clearly wants to be in the action at all times, but England should be looking to mould Ben Stokes into Jacques Kallis, not into Andrew Flintoff.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

Undoubtedly, there are reasons why Stokes at three would be a gamble. If the experiment fails, then it leaves England with precious little time to settle on a new No.3 before the Ashes – but that is true of any player. Trying Joe Clarke, Ollie Pope, or even a veteran like Joe Denly, would carry the same risks, with all the added ones of having to introduce a new personality into the dressing room.

This reshuffling needn’t be the case for all conditions. There may be better candidates for the role on spinning tracks – i.e. Sri Lanka and in all likelihood, the West Indies – and there is no doubt that Stokes’ qualities are more obviously in play on harder, bouncier tracks. But as a new default option, with tours of New Zealand and South Africa coming up in 12 months time, England may find that for Ben Stokes, three is the magic number.