The glory of Kirkby-in-Ashfield, home of women’s cricket legend Enid Bakewell, with whom Joe Wilson spent an interesting day.

This article first appeared in issue 14 of The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM9

Originally published in 2016

The United Nations list of World Heritage sites does not appear to include any cricket venues. If it did, there would be obvious candidates: Lord’s, the MCG, Newlands, perhaps Mumbai’s Brabourne stadium might immediately cross your mind. The Morrisons car park, Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire might not.

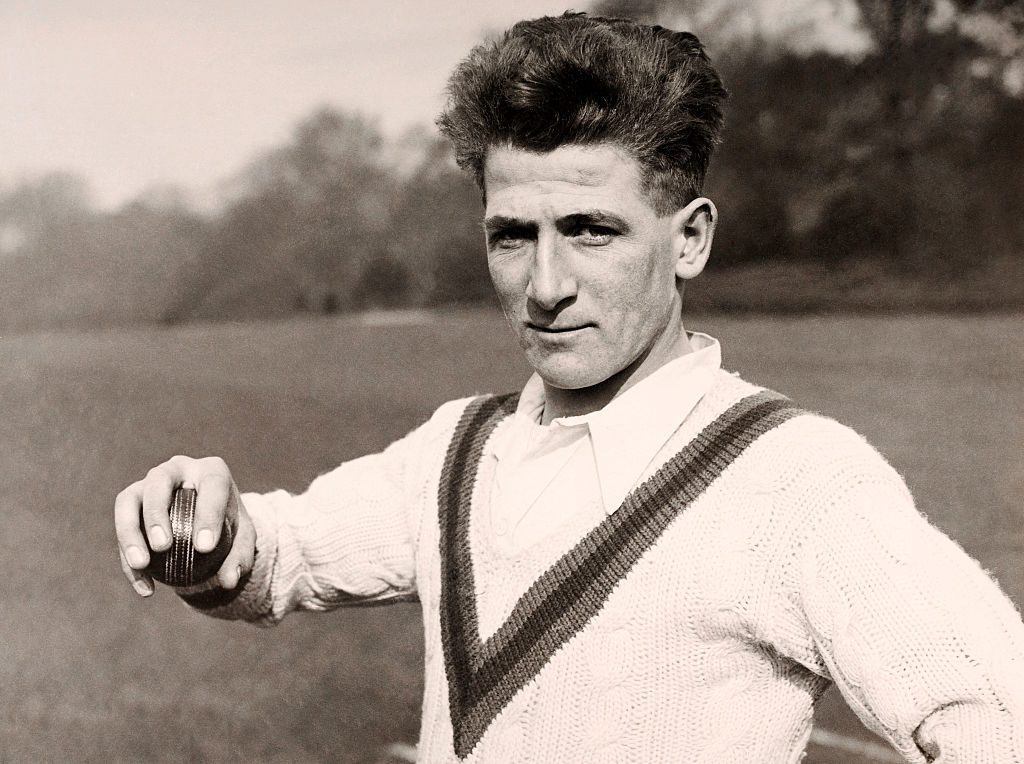

Enid Bakewell has come to meet me here, but she’ll gladly engage any passer-by. She knows every inch of this town. She knows that the statue of Harold Larwood was relocated recently as part of a town-centre regeneration. Now he bowls to a bronze Bradman just between the library and the entrance to the new supermarket. Bill Voce, a little incongruously, crouches to field at silly mid off. After all, this display immortalises the series. If not bowling you’d have thought Voce might at least have been fielding on the leg (theory) side.

But Kirkby-in-Ashfield knows its cricket history; it remembers its famous cricketing sons and can claim 22 first-class players, including Larwood and Voce. But look a little harder and you’ll also find one of cricket’s greatest female players. Enid Bakewell has just been waiting for the rest world to discover her.

[caption id=”attachment_75935″ align=”alignnone” width=”680″] Bakewell at The Sunday Times and Sky Sports Sportswomen of the Year Awards in 2015[/caption]

Bakewell at The Sunday Times and Sky Sports Sportswomen of the Year Awards in 2015[/caption]

“When the girls got their sponsorship deal with Kia I went along to one of their showrooms, near here. I said ‘you know you’re giving all the England players a new car? Well, I played for England for nearly 20 years.’

“It didn’t work. ‘We know about cars, not cricket,’ they said. But when I brought it back in for a service they did knock 40 quid off,” Enid laughs. She often laughs.

I’m pleased to have caught up with her, she’s busy. She rearranged a bowls match so we could do an interview, she’s dressed in a fleece and tracksuit bottoms because she’s taking a cricket coaching session at 5.30. Oh, and she’ll go directly to yoga after that. This might be the time to point out that Enid Bakewell is 75 years old.

Before we sit down to chat in the supermarket cafe she takes me to a newly pedestrianised precinct just a few strides from the Larwood statue. The artwork here is creative but a little less obvious. Various images from the town’s history are displayed on the walls as if they’ve been photocopied in monochrome onto the brickwork. One of them is a bob-haired batter, turning to look over her shoulder as she flicks the ball down to fine leg. Pads, knees and pleated skirt, it’s Enid in action. She poses for a photo for me in front of it.

[breakout]When the girls got their sponsorship deal with Kia I went along to one of their showrooms and said ‘you know you’re giving all the England players a new car? Well, I played for England for nearly 20 years’[/breakout]

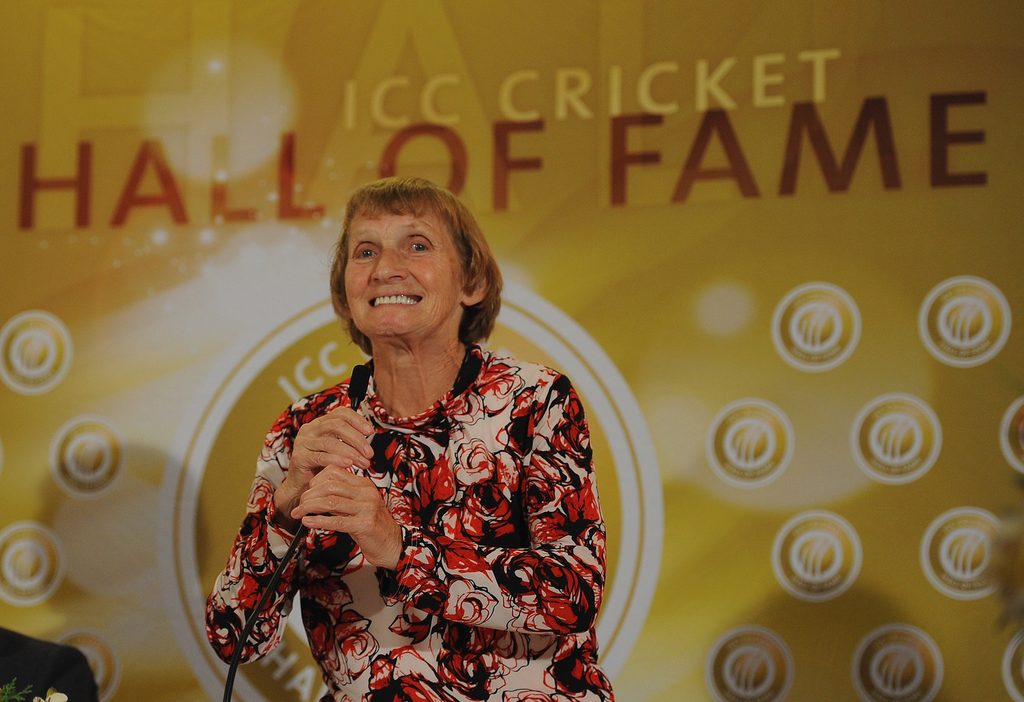

Enid is not one to be bogged down by statistics, but a few are worth noting. She started her England career in the 1960s and finished in the 1980s. This was an unrelentingly amateur era for women’s cricket. But in her 12 Tests Enid made four hundreds and seven fifties. She also took 50 wickets at an average of just over 16. In her last Test, against West Indies in 1979, she made a hundred and took ten wickets. She also helped England win the first World Cup, in 1973 (two years before the men’s version began), scoring 118 in the de facto final against Australia at Edgbaston. Only five female cricketers have been inducted into the ICC’s Hall of Fame; Enid was the third.

“What did you get paid for winning the World Cup, Enid?”

“Paid?” she replies. “Are you joking? We didn’t get paid anything. Honestly, we were not allowed to claim travelling expenses.”

By 1973 Enid was in the prime of her cricketing career. She was also a mother of three children.

“They told us the children couldn’t be with us during the tournament. We thought that was dreadful at first but in the end it helped, it helped us concentrate on the cricket. My mum had died in 1970 so my dad – who was 75 at the time himself – was absolutely marvellous. He used to take the children to the beach or the zoo.”

Surely she at least indulged in some sort of celebration on the night of the final, I suggest?

“I went home that night to see the kids, and then I had to come back to Birmingham the next day because we were playing this Rest of the World game.”

[caption id=”attachment_75934″ align=”alignnone” width=”1024″] Harold Larwood in 1928[/caption]

Harold Larwood in 1928[/caption]

Talk to Charlotte Edwards or Sarah Taylor about Enid Bakewell and their faces light up. As women’s cricket becomes properly professional, she is a living, breathing, testament to how far it has come. She’ll tell you stories about selling bars of chocolate at committee meetings at Trent Bridge to raise funds for women’s cricket. Or about being picked to tour Australia in 1968 and then being told she had to pay for the flight herself. She raised the money and went, having agonised about leaving her daughter behind, aged two and a half.

“I kept saying, ‘I can’t leave her,’ but my mother – with her first grandchild – said ‘we’ll have her.’ I said, ‘Mummy’s coming back when the daffodils are up.’ Of course, they came early that year didn’t they….”

What Enid sees of modern women’s cricket she enjoys.

“It’s phenomenal, “ she says, “they’re so good at these reverse sweeps, so improvised. There’s so much watching and analysing now, which we didn’t have.”

Back in the 1970s, female cricketers were often lacking even the basics. During the early stages of the 1973 World Cup, England had a game against New Zealand in Exmouth. The rain had fallen heavily.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”0″][/breakout]

“A lot of the girls didn’t have spikes in those days, would you believe? The umpire decided, because we weren’t wearing the right gear, someone was going to have an accident. So she stopped the game. We were behind the run rate. Shoes stopped play. England lost.”

These days women’s cricket is becoming a year-round pursuit for the very best players. Alongside the international fixtures, the Women’s Big Bash League is now established in Australia and a new six-team league starts in England this summer.

As a young woman, Enid played hockey during the winter months and cricket during the summer. As much as she loved the competitive nature of hockey and the camaraderie, Enid admits she’d have been tempted to have done nothing but cricket if she’d been blessed with modern opportunities.

“I wouldn’t have got bored, I’d have probably got better. It does rile me when they say to Charlotte Edwards, ‘when are you going to give up?’ [Edwards is 36 years old.] Why don’t they just leave her alone? I didn’t give up until I was in my forties. I remember sitting at the airport thinking ‘this is the last time I might be wearing an England blazer.’ Mind you, we had to provide those too.”

[caption id=”attachment_75938″ align=”alignnone” width=”1500″] Bakewell inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame in 2012[/caption]

Bakewell inducted into the ICC Cricket Hall of Fame in 2012[/caption]

Enid has so many stories. But it would be deeply unfair to suggest she spends her time in the past. Few people I’ve met embody the ethos of ‘get busy living’ quite like Enid Bakewell. This is, again, where the statues come in. Enid was invited to the grand opening alongside the supermarket.

“When they unveiled the statues there were some girls there in school uniform. One of the dads was at school with my eldest. She’s 50 now. Anyway, I’d got there early because I wanted to do my shopping. Luckily my son said to me, ‘look, there’s some people there, don’t you want to go and talk to them about cricket?’ Well, we got talking, and it turns out, now the dads want their daughters to play.”

Kirkby-in-Ashfield is suffering from the same issues that face so many parts of the British cricketing landscape: in short, fewer clubs and fewer teams within those clubs. I was told that Kirby alone once boasted six cricket clubs. That figure is now one. But Kirkby Portland is not standing idly by. Terry Barrett from the club hands me a sheet of A4 paper that condenses Kirkby Portland’s history with key dates and achievements. They include the following:

1878: Club formed. Played on farmer’s field near Portland colliery

1908: Notts Senior League champions

1921: Notts Senior League champions and Notts Senior League Cup winners

1978: Celebrated centenary with match against local celebrities. Took out 20-year lease on Nuncargate Cricket Ground (where Harold Larwood first played cricket)

2003: Recognised as ECB Focus Club

2015: Kirkby Portland Girls Team formed

That last entry is why we’re in a school hall with the matting wickets on the floor and the nets pulled into place. Enid has got her pads on and is now wearing her MCC jumper. She’s over in the corner, shouting “Well done, lass!” More children are arriving all the time, some boys, some girls.

As the chairman of Kirkby Portland, Kevin Jones is charged with protecting the club’s future. Some of the challenges he faces are those you’ll often hear in connection to youth sport in modern Britain. For example, Kevin believes interest in cricket is affected by the range of alternatives for young people. But in Nottinghamshire, in particular, Kevin knows cricket has been damaged by the decline in traditional industries, like the collieries that produced Larwood.

[breakout]The girls tend to listen more, they don’t want to show off so much, they’ve got a greater focus and I think they’ve got greater grace when they play[/breakout]

“You do not have that unity of purpose in regards to the ordinary man. You do not have the same communities because they’re not all working in the same areas. Around here there’s still a working-class base but its not a working-class base that stands up for itself like it once did, and Larwood can be seen as an embodiment of that.”

Over 80 years on, Larwood’s treatment at the hands of the establishment in the wake of the Bodyline series is still an open wound here. He refused to apologise for doing what the captain had told him. He didn’t play for England again. The word is scapegoat, I suggest. Both Kevin and Terry nod.

“People here still feel for him as someone who was treated with contempt, treated poorly by the authorities,” is how Kevin puts it.

As for the future of cricket here, a key part of the club’s policy is establishing female participation.

“I would sooner work with the girls,” Kevin tells me. “They tend to listen more, they don’t want to show off so much, they’ve got a greater focus and I think they’ve got greater grace when they play.”

[caption id=”attachment_75933″ align=”alignnone” width=”2040″] Bakewell in England action[/caption]

Bakewell in England action[/caption]

The club has linked up with Chance to Shine, the charity that tries to ensure cricket participation in state schools, but the chance to get Enid involved was too good to miss.

“She used to live at the bottom of the street where we lived,” Terry Barrett explains. “I grew up hearing about ‘Enid Bakewell used to play for England,’ and thinking, ‘but this woman only just lives down the road!’ It was great for the area, along with all the other cricket history we’ve got around here.”

When Enid tried to teach cricket in PE lessons in Nottinghamshire in the 1960s she was told by her (female) PE adviser “Ooooh no! That’s too unladylike!” Nowadays she helps out at Kirby Portland on a voluntary basis – she’s been teaching sport her whole adult life. But she’s aware of how she needs to adapt.

“It’s interesting, having watched this Twenty20, the way that [players] are improvising. It makes you think. There are some keen lasses, but it’s no good being traditional. If some kiddy has got talent and they’ve got an eye for the ball, you’ve got to build on that positively. It’s no use trying to play by the book or coach by the book. I mean, I was never coached how to bowl.”

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”1″][/breakout]

Only twice during my time with Enid does she express anything approaching regret. On the 1968–69 tour of Australia she turned down a chance to go and visit the man who is still the most famous cricketer in Nottinghamshire. Harold Larwood had emigrated in 1950.

“We were told he was very shy, and I was exhausted from all my efforts playing, but I’ve always regretted not meeting him.”

The other uncertainty that Enid Bakewell confesses is her fear that she’s taken up bowls too soon. After all, with matches scheduled for MCC and the Redoubtables Club this season, her cricket career is far from over.

“I’m going to try to keep going until I’m 80, at least. I once saw a chap at Timperley captaining a side, standing at mid off, and he bowled an over. He was talking about all the lads he’d coached. And I thought, if I can do that when I’m 80, I’d feel very, very proud.”

Building a statue of Enid Bakewell would almost seem inappropriate. After all, in her life thus far, she has never remained still.