As Surrey’s director of cricket, Alec Stewart has overseen his county’s first County Championship title since 2002. Last month, with the club on the verge of success, the self-styled ‘Gaffer’ sat down with WCM editor-in-chief Phil Walker to discuss his coaching philosophy, what he’s learnt from Fergie’s United, and how he hopes to build a dynasty that will last.

When Alex Ferguson arrived at Manchester United in 1986, he found an ailing institution, one grown musty in the 21 years since their last league title. The senior players were neither young nor in great shape. The youngest player on the whole staff was 24. Ferguson looked about the place and concluded that something had to be done.

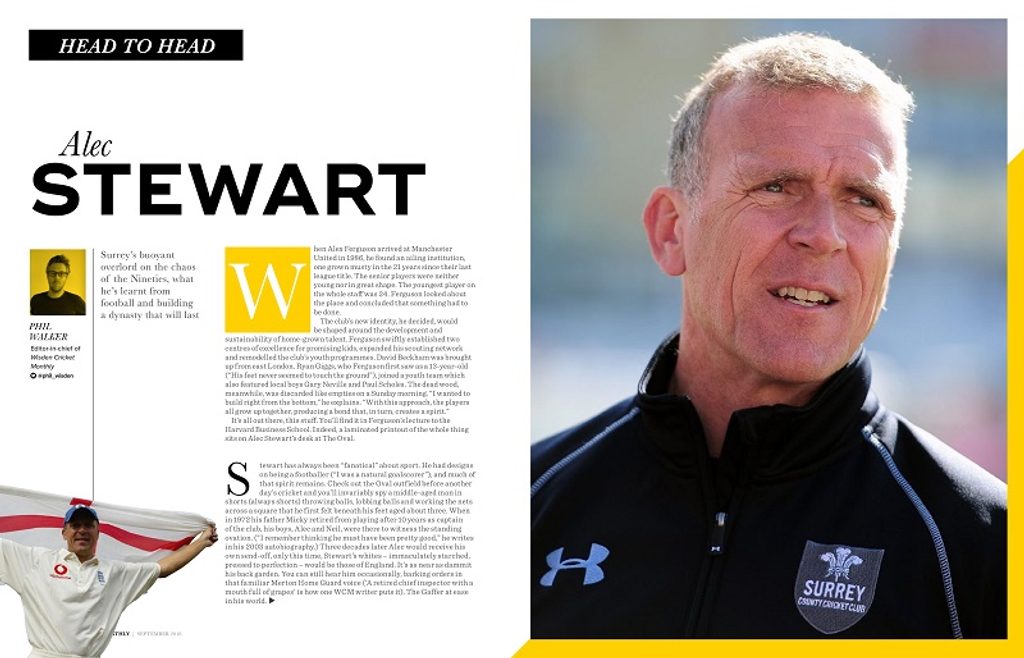

[caption id=”attachment_81531″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Alec Stewart issuing subtle praise during one of his pre-match fielding drills[/caption]

Alec Stewart issuing subtle praise during one of his pre-match fielding drills[/caption]

The club’s new identity, he decided, would be shaped around the development and sustainability of home-grown talent. Ferguson swiftly established two centres of excellence for promising kids, expanded his scouting network and remodelled the club’s youth programmes.

David Beckham was brought up from east London. Ryan Giggs, who Ferguson first saw as a 13-year-old (“His feet never seemed to touch the ground”), joined a youth team which also featured local boys Gary Neville and Paul Scholes.

The dead wood, meanwhile, was discarded like empties on a Sunday morning. “I wanted to build right from the bottom,” he explains. “With this approach, the players all grow up together, producing a bond that, in turn, creates a spirit.”

It’s all out there, this stuff. You’ll find it in Ferguson’s lecture to the Harvard Business School. Indeed, a laminated printout of the whole thing sits on Alec Stewart’s desk at The Oval.

***

Stewart has always been “fanatical” about sport. He had designs on being a footballer (“I was a natural goalscorer”), and much of that spirit remains. Check out the Oval outfield before another day’s cricket and you’ll invariably spy a middle-aged man in shorts (always shorts) throwing balls, lobbing balls and working the nets across a square that he first felt beneath his feet aged about three.

When in 1972 his father Micky retired from playing after 10 years as captain of the club, his boys, Alec and Neil, were there to witness the standing ovation (“I remember thinking he must have been pretty good,” he writes in his 2003 autobiography).

Three decades later Alec would receive his own send-off, only this time, Stewart’s whites – immaculately starched, pressed to perfection – would be those of England. It’s as near as dammit his back garden. You can still hear him occasionally, barking orders in that familiar Merton Home Guard voice (‘A retired chief inspector with a mouth full of grapes’ is how one WCM writer puts it). The Gaffer at ease in his world.

[caption id=”attachment_81529″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] The full interview was originally published for issue 11 of Wisden Cricket Monthly[/caption]

The full interview was originally published for issue 11 of Wisden Cricket Monthly[/caption]

His office in the Micky Stewart Members’ Pavilion overlooks the ground. Right opposite is the OCS Stand, a monument to Surrey’s vaulting ambition and a reminder to the rest just how “unique” (Stewart’s words) the club is. Just behind the stand, you’ll find the Alec Stewart Gates. The Oval cricket ground, open for business since 1845, framed by the family name.

It felt inevitable that Stewart would one day be sitting in this chair. He made his debut in 1981 and would feature in 266 first-class matches for the club over the next 22 years, making over 15,000 runs and claiming 407 dismissals. As part of Adam Hollioake’s great team of the late Nineties-early Noughties, he won three championships in four years.

After his retirement in 2003, Stewart tried other things – notably a bit of commentary – but it was all just a bit too smooth. He wanted to be “challenged” again, to seek out more of these “real achievements” which have defined his life.

He needed to be back in the dirt. He’s been in situ as Surrey’s director of cricket since February 2014. This is his fifth full season in charge. And now they’ve cracked it.

***

[caption id=”attachment_81526″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Stewart honourably handed Sam Curran with his first England Test cap earlier this summer[/caption]

Stewart honourably handed Sam Curran with his first England Test cap earlier this summer[/caption]

By a certain measure, they’d cracked it a while ago. A cursory look at the England Test side of this summer reveals a pair of homegrown products in Ollie Pope and Sam Curran, totalling 41 years between them, while a glance at the one-day team throws up Jason Roy and Tom Curran. For all that other counties will sniff at (and live in fear of) Surrey’s pulling power, these players all came up through the academy, and there will be more.

Stewart has been around this stuff forever, and the buzz never fades. “Seeing Pope or a Curran play for England, seeing Surrey win a game, seeing a certain player score a hundred or take a five-for, you feel massively proud for them, but also a little bit of pride that you played a small part in helping them succeed.”

Additionally, Surrey has reach beyond that of other counties. King Kumar had three years at the club. When he went, Morne Morkel stepped in, and has been immense as the spearhead of Surrey’s march to the title. Aaron Finch has opened superbly in the short stuff, while the Virat Kohli flyby was definitely on the cards before injury curtailed it, breaking a few treasurers’ hearts in the process. But Surrey will say that these names are only discussed because the rest of the business is thriving.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]Stewart won’t badmouth his predecessors, but the inference is clear. “My thing is: If you’re going to have a plan, it has to be a long-term plan. If you just want a quick fix, you’ll only sign ready-made players, which is too short-term. If you’re trying to build something with longevity, you’ve got to make sure you have the balance right between senior and junior players.”

Echoing Ferguson, one of the first things he did was to challenge the academy director, Gareth Townsend. “I said to him, ‘Give me players that I don’t have to educate massively’. I want them to be replicating what is expected here. Can they field? Are they fit and strong enough? Are they athletes? Do they understand the strength and condition that is required to be a top-class cricketer?” In the last three years, he adds, “We’ve seen improvements in that”.

Stewart doesn’t do grandstanding. Losing more Test matches than all but four men in history instills a certain cautiousness, if not humility. But while he’s reluctant to take much credit, he’s happy to take a little.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]“It’s a unique club, Surrey. It’s London, it’s a big club. There’s a massive expectation here. I have an advantage. I’ve known the club all my life. I think I know how it works, I know what the expectations are from up above. So when they asked me to come back, I said, ‘Only on the understanding that you allow me the freedom to put in place what I believe is the right way. If it works, you can pat me on the back. If it doesn’t, kick me out’.

“I’ve been challenged but there hasn’t been an interference. Whether it’s the appointment of coaches or the signing of players, I’ve generally been able to get that. I don’t give team talks. It’s their team, it’s their dressing room. Obviously I put the team together, but we’re always sharing ideas, always discussing, always talking.”

***

Perhaps Stewart has now grasped the cohesive operation he always craved as a player, but which never quite materialised. Throughout that tragi-comic, routinely mythologised decade Stewart was its upstanding anomaly, his collar upturned to the chaos that swirled around the England team in the Nineties.

[caption id=”attachment_81539″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Stewart batting for England at Eden Gardens, Kolkata, January 1993[/caption]

Stewart batting for England at Eden Gardens, Kolkata, January 1993[/caption]

He was once, all too briefly, the team’s gun opening bat, a natural back-foot counterpuncher, brilliant on the pull, brave and sound of technique. But when times got tough, his competency with the gloves came to be seen as more valuable than his skills against the new ball. In 1996/97 he was shunted into the middle-order and told to keep wicket.

“If you’d gave me the option of opening, I would have said, ‘Yes I’ll carry on opening, thanks’. But you’re not given an option. They weakened a strength which was me opening the batting with Athers [Michael Atherton] to try and strengthen a weakness with me becoming the all-rounder. Selection back then was hit and miss at the best of times.”

Despite moving down the order, he still scored more Test runs than any other man in that decade. He also lost more matches.

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]Fittingly, the end of it, in 1999, was marked by a botched and fractious World Cup campaign on home soil. There was an issue over money, with the squad deeply unimpressed by the pot offered by their bosses. The team’s preparations for a May tournament in England consisted of a few games on the subcontinent on raging turners.

Stewart and the coach David Lloyd were then informed that they would not be getting the team they wanted, with the selectors refusing to countenance Chris Lewis’ presence anywhere near the squad (“Why? You’d have to ask the selectors that”). It all added up to an exit at the group stages, and the inevitable front-page lampooning of our once-great national sport. Stewart never captained England again.

Still, as England’s fortunes began to change, Stewart would enjoy his final years as a player. There was success versus the West Indies, including a century in his 100th Test – against Ambrose and Walsh, whom he’d famously taken for a pair of centuries at Barbados in 1994. He was part of the series wins in Sri Lanka and Pakistan in 2000/01, and in 2003 was afforded the dream finish on his home ground with a stunning series-levelling victory against South Africa.

[caption id=”attachment_81527″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Despite the number of low-points during the 90’s, Stewart did manage enjoy a few smiles in England whites[/caption]

Despite the number of low-points during the 90’s, Stewart did manage enjoy a few smiles in England whites[/caption]

Australia, of course, remained uncrackable, but Stewart did at least have his own riposte to all that dominance. As captain on the 1998/99 tour, and long-since resigned to having to keep wicket, the teams got to Melbourne for the fourth Test and with his old alter ego Atherton indisposed with a bad back, he gave the gloves to Warren Hegg and promoted himself back to opener. The century was inevitable. The 12-run victory rather less so.

***

It was 16 years since the richest and most ambitious club in the country won the County Championship. Now the foundations are in place to maintain success well after the champagne has been drained on this one. “What we are saying is: ‘Play in this manner’. We’re playing disciplined but confident cricket. Ruthless cricket. In a structure which has longevity. It isn’t just pot luck.”

[caption id=”attachment_81532″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] A ‘thumbs-up’ certainly becoming a familiar sight around The Oval during Surrey’s 2018 County Championship campaign[/caption]

A ‘thumbs-up’ certainly becoming a familiar sight around The Oval during Surrey’s 2018 County Championship campaign[/caption]

Stewart has just won his first championship with a side boasting nine homegrown players in its ranks when the pennant was secured at Worcester. He is a firm believer that teams of individuals cut from the same fabric pull together to create their own spirit. The rest of the county game, often on its uppers, casting envious glances towards south London, will have observed the Stewart revolution keenly; and will be acutely aware that this is merely the start.

…

The full interview was initially published for issue 11 of Wisden Cricket Monthly, available to purchase HERE.

To discover more Wisden interviews and features, subscribe to WCM today.