Jack Russell – the greatest wicketkeeper of his generation – lets Tanya Aldred into his world in Issue 6 of the Pinch Hitter.

The Pinch Hitter aims to help out freelance cricket writers during the current coronavirus crisis. Read on a pay-what-you-can basis here

Jack Russell likes Coco Pops. He also likes Rice Krispies. In fact it turns out that the only reason he ate that famously soggy Weetabix every sodding lunchtime was that it was less messy than other cereals and easier for the 12th man to prepare. And, AND, he gave it up for 15 years after finishing cricket. Just like that.

Russell was one of England’s very best wicketkeepers, lean, agile and sharp, especially up to the stumps. He played 54 Tests between 1988 and 1998, taking 153 catches, making 12 stumpings and two Test centuries with his unorthodox jabbing style. Over that time he fell in and out of favour as England’s selectors tried endlessly to re-patch a sow’s ear, shoehorning Alec Stewart in as a wicketkeeper to bolster the batting.

But it was Russell’s idiosyncrasies that appealed to the public almost as much as his keeping: his obsession with his kit, his favoured old saggy cloth hat, his long comb moustache, his constant tea drinking, his food habits, the obsession with privacy.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

“People call them eccentric but I just did what I felt was needed at the time, Tanya,” he says in his glorious Gloucestershire burr. “The Weetabix added carbohydrate at lunchtime rather than something like Sunday lunch which made you feel heavy and wasn’t so easy to dive around after eating. My kit was important to me. I had my hat the whole of my career, people thought it was a superstition but it was just a comfort thing, and I had two pairs of wicketkeeping gloves in 20-odd years.

“My wife is the only person I allowed to repair the hat. The only material we could use was old-fashioned cricket flannels from the 1950s and 60s, so I used to go round to my old county coach’s house and cut a piece out of one of his old trouser legs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgn4f8xDYI8

“The hat is in a safe place because otherwise I have a panic attack. When I was playing I would never leave it at the ground and if we were playing abroad I’d take it and my gloves in the hand luggage, which used to cause a bit of a scene as my gloves used to smell a bit so no one really wanted to sit next to me. When we got woken up by fire alarms at hotels I could be seen outside the hotel holding my hat and gloves. They were like part of the family.”

So not eccentric at all. But what about blindfolding builders before they came to his house, did that really happen?

“Only because they didn’t want the pressure of knowing where I lived in case the papers interrogated them and they succumbed to the pressure. I started it, not telling the press where I lived, because we lived in the country in a house by itself and if I was away in the winter – it was a bit of a security thing really. I wanted the family to be away from it all. Occasionally I would go around the roundabout a few times to lose people in case they were following me – Jason Gallian and Clive Rice did one night, right down the motorway. I went round and round until they left. I thought, ‘I’ll do this all night if I need to’. If you look at it psychologically, I’ve probably got a major problem but we won’t go into all that!”

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]

In 2004, aged 41, he had to retire suddenly after a recurrent back injury, just after signing a new two-year deal with Gloucestershire, but there was never any question of what he was going to do afterwards. His painting career was already flourishing, and there was nothing he wanted to do more than retire to his studio and paint all day, every day.

He’s just coming to the end of a big project – paintings of the first ball of every Ashes Test last year, plus the World Cup final and the Women’s Ashes Test. “It’s a self-inflicted challenge, I don’t think any artist has ever done it before and, because the pictures are so big [4ft x 3ft], I’m practically painting every spectator. It’s great fun. It was the first time I’ve done a women’s Test and I was excited to do that because the detail is slightly different, the girls move differently and they’ve got long hair down the back of the necks. I enjoyed it.”

In fact lockdown hasn’t affected him too much at all, apart from breaking at 5pm every evening to watch the coronavirus news conference. It has suited his rather reclusive nature.

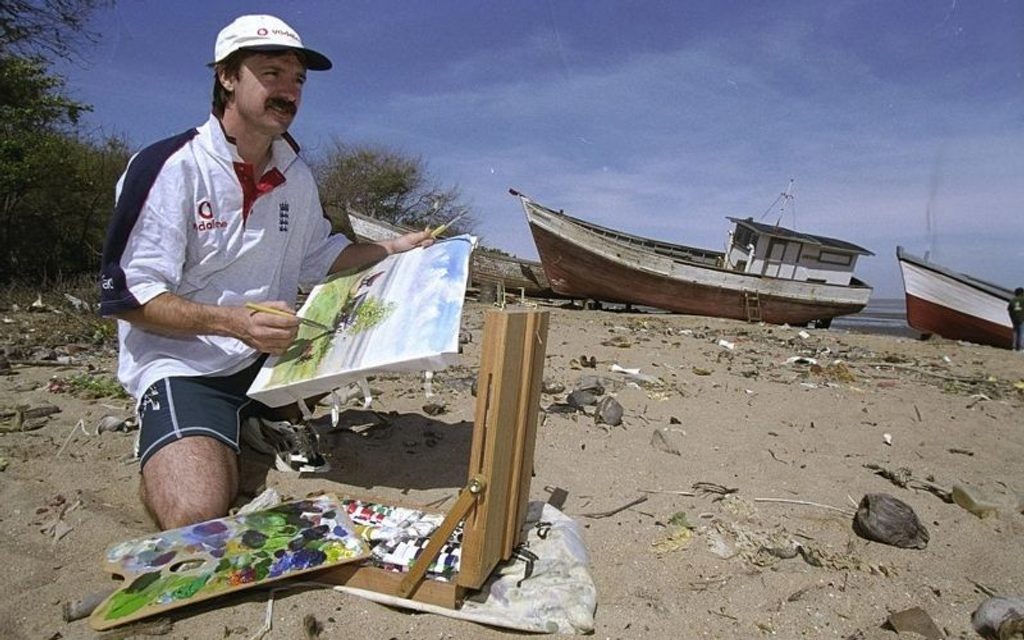

[caption id=”attachment_162023″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Jack Russell indulges in his favourite pastime in Guyana during the 1998 tour to the West Indies[/caption]

Jack Russell indulges in his favourite pastime in Guyana during the 1998 tour to the West Indies[/caption]

“Maybe recluse is slightly too strong a word but I’m a bit of a loner, I never get bored, I’ve always found being on my own recharges me. So when we were touring I’d go painting on my day off while the lads would sit round the pool. Sometimes I’d say to Athers, ‘I don’t need any practise tomorrow, can I go and paint?’ and he’d say, ‘Yes, just go’.”

It is quite a balancing act, to reconcile these two parts of his personality, the recluse and the exhibitionist always up to the stumps and in the batsman’s ear.

“Cricket is like a stage and I quite like being on the stage, especially places like Lord’s, the greatest stage of all for a cricketer. Being in crowds of people isn’t a natural thing for me because I’m quite shy but it balanced my life out.

[breakout id=”3″][/breakout]

“I went hell for leather when I was a teenager and then nearly got sacked. I knuckled down when I was 20ish and had all that discipline. I always thought that I could drink for the rest of my life when I’d finished playing so I sacrificed all that to do as well as I could. And since then I’ve lost all discipline. I thought I’d have a year off going to the gym when I stopped playing and now I’ve had about 16 years off and I can’t be bothered.”

He’s not stayed completely out of the public eye. He coached at Middlesex and meets people when he does exhibitions round the grounds, but he doesn’t stay in touch much with old teammates, except via Twitter, and doesn’t really miss playing, “though I get a bit itchy when the Aussies are in town”.

[caption id=”attachment_162024″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Russell at work during last summer’s Women’s Ashes Test[/caption]

Russell at work during last summer’s Women’s Ashes Test[/caption]

In his later years with Gloucestershire, especially when they were winning limited-overs tournaments by the handful – six between 1999 and 2004 – he was a key member of the team and exponent of their strategy.

“My job was to irritate the opposition and I used to do it so much I’d irritate myself. Part of our game was to get the keeper up to the stumps and strangle the opposition batsman, so myself and the close fielders used to isolate him. It was an important part of building pressure. I used to visualise having my hands round the batsman’s throat without physically doing it. It used to get quite comical at times. My teammates used to say, ‘Breathe on him, Jack,’ so I’d have to. It would be part of my mental disintegration of the opposition.”

Not ideal for these times of social distancing. “No, I couldn’t have coped at all.”

[breakout id=”4″][/breakout]

Can he put his finger on what made him so good, the best in the world for a period of two or three years?

“I was obsessed with it, it was my life. Even when I got married, cricket was always the top of the list, even ahead of the kids, not in terms of your heart but in terms of trying to be professional. I was obsessed with practise. According to Derek Pringle, I’ve got OCD. I didn’t ever get bored with catching 600 cricket balls a day. Quite often I played Test matches when we’d be in the field from Thursday morning till what I used to call Grandstand on Saturday lunchtime, and my mental endurance was strong.

“The concentration levels have to be extreme if you’re stood up but it took me a couple of years to learn to do that and probably another 10 to 20 to get it right. I’d push the limits and push the limits and in a lot of my practises I did things to breaking point. It’s like with my painting now, I don’t know how my wife puts up with it. If I spend the day not painting I go nuts. Yesterday I did about 12 hours of admin so last night I was a bit irritable. In a nutshell, I’m either in, or not.”

[caption id=”attachment_162019″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Jack Russell with Mark Alleyne during the Gloucestershire glory days[/caption]

Jack Russell with Mark Alleyne during the Gloucestershire glory days[/caption]

There is another obsession. He likes old things, vehicles and relics. “Every so often I have to paint a steam engine. I like old lorries. I have actually renovated an old coal wagon, which is on the Severn Valley railway museum site. It took us about four years, me and a couple of lads. I don’t tell people because it is quite anorakish and boring.”

The state of English wicketkeeping at the moment is a matter of deep satisfaction, he thinks half a dozen could be in the running to be the best in the world. “Ben Foakes is probably the most natural, John Simpson at Middlesex is very good, the lad [Ben] Cox at Worcestershire does brilliant things, [Jonny] Bairstow’s come on a lot. And I know it is my old county, but James Bracey of Gloucestershire has got a tremendous amount of ability.”

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

He wears glasses these days and he’s still got the moustache, though he’s trimmed it down a bit. “When I was a kid I used to shave it 10 times a day to try and make it grow, but I’m paying the price now because it gets out of hand. When I was playing I used to keep it quite long because I felt as if it kept the sun off my lips, so there was logic to it like all my eccentricities. And the long hair as well, to keep the sun off my neck.”

And with that he is gone, back to his oils and his canvases, his tea and chocolate biscuits, with YouTube on in the background playing a steam railway documentary. Back to that picture of Ben Stokes hitting the winning runs and the gaps where he must fill in the crowd: “Dots, dots, dots, dots and blobs of paint.” And back to all the new commissions that will keep him busy way into the new year. Back to bliss.